Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 12

May 18, 2015

In My August 6, printed in 2012, survivor describes her “new life”

A book which details an A-bomb survivor’s personal history was delivered to the team of Chugoku Shimbun reporters working on the series “Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing.” Along with the book was a note which said: “This is what my sister wrote when she knew she would soon die.”

One of the “Hiroshima Girls” who received medical treatment in the U.S.

My August 6: A New Start was written by Masako Wada. She was one of the 25 women who traveled to the United States in 1955 to receive medical treatment. They were dubbed “Hiroshima Maidens,” or “Hiroshima Girls” in the United States. Citizens in the United States and Japan worked together to realize this project, which spurred the Japanese government to begin providing support to A-bomb survivors. Two years later, in 1957, the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law was enacted.

After returning to Japan, Ms. Wada was involved in social welfare activities and rarely engaged with the media. When the Chugoku Shimbun visited her younger brother, Toshiyuki, 71, who had sent the book and lives in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, he invited the reporter into his sister’s room and agreed that her privately-issued book, of which 300 copies were printed, be made public. A year after the book was printed, Ms. Wada passed away on June 29, 2013 at the age of 81.

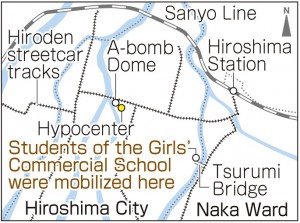

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Wada was a second-year student at Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School. When the atomic bomb exploded, she was about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, helping to tear down houses in Tsurumi-cho (now part of Naka Ward) to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. According to the Sixty-Year History of Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School, a total of 274 students who were mobilized to work at that location were killed, both first-year and second-year students.

“Because of my terrible burns, it was hard for people to pick me up and put me on a cart,” Ms. Wada wrote, recounting what she heard later from her father, who had brought a cart to take her home. Ugly scars then remained on her skin.

When Ms. Wada was 22, she underwent an operation at Osaka University Hospital, along with other women suffering the same plight. Toshiyuki said that when he was a young boy, his sister closed herself off from others, even her own family. “But she changed a lot after she went to the United States,” he said, looking up at her portrait on the wall.

Providing medical treatment in the United States was proposed by Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto (1909-1986) of the Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church and Norman Cousins (1915-1990). Mr. Cousins also promoted the “moral adoption” of A-bomb orphans. In Hiroshima, there was some criticism against the idea of medical treatment by the country which had dropped the atomic bomb.

Mount Sinai Hospital, one of the best hospitals in New York, agreed to perform the plastic surgery, and Quaker families, who were pacifists, took in the women and provided for their daily needs.

Ms. Wada underwent six operations and stayed in the United States for 13 months. Although she did not understand English, she wrote, “They accepted me not as a survivor of the atomic bombing but as a human being.” She also wrote, “The scars on my face were still there, but the scars in my mind were healed.”

Working in social welfare, determined to help others

“Do for others what they did for you to make you happy.” With this motto in mind, she started a new life. When she returned to Japan, she enrolled in a part-time course at her high school and obtained her high school diploma. At the age of 27, she entered Meiji Gakuin University, then graduated. In 1963, she began working at the Hiroshima Christian Social Center, run by the Nishi Chugoku Christian Welfare Organization (in today’s Nishi Ward). She then served as the head counselor at Seirei-en, a special nursing home for the elderly established by the same organization in 1971 in today’s Hatsukaichi City.

At work, Ms. Wada saw aging A-bomb survivors and those who had lost their families because of the atomic bombing. When August 6 approached, she held “peace gatherings” at the nursing home so people could voice their experiences of the war and the atomic bombing. Thinking about her late classmates, she wrote:

“They died a ‘death in war,’ all alone, without anyone by their side. They had to go through such a sad, miserable ending to their lives. I strongly believe that, whatever happens, we must preserve the conditions in which people can die in peace, a ‘death in peace.’”

When Ms. Wada was 80 years old, she learned that her cancer had metastasized. She repeatedly told Toshiyuki that she did not want treatment to prolong her life. She wrote about her life as she was fighting the cancer. At the end of My August 6, she asks her nephews, nieces, and their children to continue sending out messages of peace. Toshiyuki, who spoke for the family at Ms. Wada’s funeral, agreed that the book be made public because he wanted to convey his sister’s hope more widely.

A-bomb survivors have continued to write about their experiences, as indescribable as they, with the desire that nuclear weapons never again be used on human beings. Many of these accounts are still waiting to be read.

*This article concludes the “Paper Monuments” series.

(Originally published on April 21, 2015)