Former junior writer interviews second-generation Japanese-American, caught between two countries in World World II

Oct. 9, 2014

Rena Sasaki, 17, a former junior writer of the Chugoku Shimbun and a high school student in the U.S. state of California, interviewed a second-generation Japanese-American in the United States, whose parents were from Hiroshima. She asked him about his life in America during World War II and about his experience in Hiroshima as an American soldier after the war.

◇

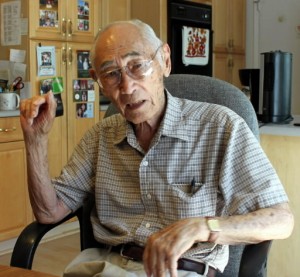

Masuo Kumamoto, 93, a second-generation Japanese-American who lives in California, remembers his grandmother saying to him, “Did you drop the bomb?,” when he visited Hiroshima soon after the war ended, in the autumn of 1945, as a member of the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS).

Mr. Kumamoto was born in Los Angeles. His parents were from Saka Town and Kure City in Hiroshima Prefecture. After he graduated from high school in the United States, as the oldest son of a farmer, he pitched in to help his family.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, most people of Japanese ancestry were sent to internment camps. Mr. Kumamoto still remembers when his father, Masuzo, was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as a “teikoku-jin” (“person from the empire”). After his father was arrested, the rest of the family were sent to the temporary assembly center at Santa Anita near Los Angeles for about three months and then to the internment camp at Rohwer, Arkansas. Mr. Kumamoto was there for about three years with his mother, Hisayo, his younger brother, and his two younger sisters.

Because he was a U.S. citizen, he was drafted into the army in December 1944 and assigned to the MIS, composed of Japanese-Americans who could speak Japanese. Later, his brother, Katsumi, who was three years younger, also joined the army.

Mr. Kumamoto mainly served as an interpreter and translator between Japanese and English. He was dispatched from the Philippines to Tokyo, and two months after the war ended, he was transferred to Hiroshima, the area where his parents’ hometowns were located. His aunt came to the city of Hiroshima to see him and took him to Kure, where he visited his grandmother for the first time. She did not, however, welcome him at first because although he was Japanese, he had joined the American army.

“Why did the United States drop the atomic bomb?” he was often asked while on duty. He could not answer this question well. It was not easy for him to interpret about the atomic bomb, which was an unknown weapon, from the viewpoint of an American soldier.

In Hiroshima, people thought that the Japanese people who had immigrated to the United States had been massacred. Mr. Kumamoto told them about his life in the internment camp and reassured them, saying that there had been no mass killings. He helped people send letters to their relatives in the United States free of charge through the U.S. military postal system, if they obtained their relatives’ addresses. Many people shed tears when they learned that their relatives were still alive.

Mr. Kumamoto’s work as an interpreter at the army had irregular hours. When he was off duty for three or four days, he bought a lot of candy and chocolate at the army store and gave them to hungry children. He even gave a 100-yen note to someone who was penniless and struggling to survive. “Buy something to eat today,” he told this person. He made it a rule never to receive anything in return.

Mr. Kumamoto is still thankful to his parents for having him attend a Japanese language school. “I was reluctant to go there, but I’m glad I obeyed my parents and went,” he said. “Thanks to them, I wasn’t sent to the front line.” He hopes that young people who have no experience of war can make friends across national borders by showing tolerance toward their differences. As a young man, because he was caught between two countries, Japan and the United States, he understands how war can hurt innocent youth.

(Originally published on September 1, 2014)