Peace Seeds: Teens in Hiroshima Sow Seeds of Peace (Part 18)

Sep. 24, 2015

Part 18: Children’s wartime pleasures, belief in the correctness of the war

The junior writers of the Chugoku Shimbun continue to meet with atomic bomb survivors, talk to them about their experiences and write articles about them. Every time we interview survivors we are struck by how much they have to say about their childhood experiences before the A-bombing: playing in rivers and at the sea, humming tunes, reading children’s books and manga that they passed around among each other. Even in wartime there were simple pleasures.

But because the government strictly controlled information, books and songs were also devoted to boosting the war effort.

What forms of amusement did young people our age have access to during the war? Among the various diversions available then, we talked to researchers and atomic bomb survivors primarily about manga, children’s books and war songs that were popular in Japan from the 1930s through 1945.

What is Peace Seeds?

The goal of Peace Seeds is to consider peace and the value of human life from a variety of perspectives and spread these values around the world to bring smiles to people’s faces. The 49 junior writers of the Chugoku Shimbun, who range from sixth graders to high school seniors, come up with their own ideas, conduct their own interviews and write their own articles.

Believing in the correctness of the war without realizing it

Manga, magazines

Fearfulness of unquestioning acceptance

Just as they are today, manga were enjoyed by both children and adults during the war. Because they were expensive, people gathered around to read them together.

I visited the Kyoto International Manga Museum in the city’s Nakagyo Ward. The facility is jointly operated by the city and Kyoto Seika University. Its collection of approximately 300,000 publications focuses primarily on items from the Meiji era (1868-1912) on. I was allowed to see some valuable manga and boys’ magazines that are not ordinarily made available to the public.

The magazine “Koku Shonen (“Youth Air Corps”), which was launched in 1942, featured illustrations and photographs of Japan’s fighter planes and downed enemy aircraft. The four-panel comic strip “Fuku-chan Jissen” was published in newspapers. In one strip from December 1941 the protagonist Fuku-chan declared, “The Japanese must rapidly advance across the sea.” Publication was then temporarily suspended because the cartoonist was sent overseas as part of the military’s Southern Operations.

Surprisingly, along with its war-related content the same magazine also featured manga that make you laugh and fascinating material on “Chushingura” (“The 47 Ronin”).

Tadahiro Saika, 35, a sociologist at Kyoto Seika University’s International Manga Research Center, said, “Publishers were trying to create interesting books. At the same time, if they didn’t include content intended to whip up support for the war, they couldn’t get paper, which was rationed in those days. This situation is behind the magazines’ dual nature,” he said.

I realized it wasn’t right to assume that everything was about the war in those days. I was surprised at how easy it was to unquestioningly accept war-related content when it was paired with amusing content. Perhaps public opinion is formed in this way without people realizing it. I wondered if I would recognize the horrors of war if I were in the same situation today.

“Stirring tales and sad stories are easily linked to the ‘cool’ aspects of war,” Mr. Saika said. “It’s important to try to see ‘amusing’ content from multiple perspectives.”

“Barefoot Gen” and other postwar manga about the war were also displayed as part of a special exhibition. Manga convey the horrors of war with a persuasiveness that differs from that of books and photographs. When I look at various works, I will continue to consider the difficulty of seeing them from “multiple perspectives.” (Nanase Shode, 16)

Children’s books

The importance of having all sorts of information

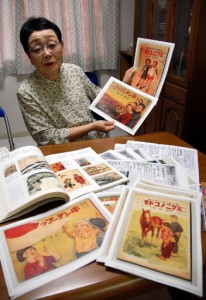

Children’s books changed with the year of publication, and I was surprised to see that they reflected the wartime atmosphere. I looked at a typical example, the popular “Kinderbook” illustrated magazine, with Hiroshima resident Seiko Miura, 79, a scholar of children’s literature.

Until the early 1930s the magazine featured colorful illustrations, such as those of toys. But in 1932, the year after the Manchurian Incident, the magazine depicted a fighter plane with “patriot” inscribed on the side. In 1942, the year after the outbreak of the Pacific War, the name of the magazine was changed to “Mikuni no Kodomo” (“Children of our Divine Land”).

The government sought the consolidation of magazines, and publication of “Mikuni no Kodomo” was suspended from 1944 through the end of the war. In April 1945, as Japan’s defeat in the war loomed, the subtitle of “Nihon no Kodomo” (“Children of Japan”), the only remaining illustrated magazine for children, was “Teki Gekimetsu” (“Destruction of the Enemy”).

Many children’s books that were popular during the war can still be read today. But, Ms. Miura, noted, “Some books were reprinted without the militaristic language. When you read them, you don’t get an accurate sense of the times.” Perhaps it would have been awkward for the writers to have it known that they had cooperated in the war effort. But we must learn from the past, not hide it and bury it in history.

When you read old books today you get the sense that they were full of war-related content. But if I had lived then I may have objected to criticism of the war. It’s important to have a society in which we have access to all kinds of information and that is not subject to government control. I feel that, as junior writers, we must also faithfully convey information that we have considered and evaluated. (Shino Taniguchi, 16)

War songs

Fond memories with mixed feelings about wrong path

♪“Soldiers are handsome. I love soldiers.”

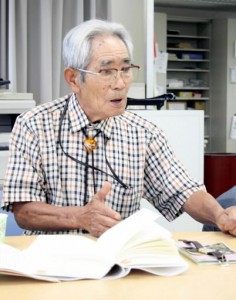

Kazunori Nishimura, a resident of Fuchu-cho, was 12 years old at the time of the atomic bombing. He still remembers a number of war songs including one called “Heitai-san” (“Soldiers”) that goes: “Soldiers are so handsome. I love soldiers.”

Mr. Nishimura learned war songs by listening to them on the radio and was taught them at school as well. “I fully believed that the lyrics were correct,” he said. “Even if I had doubted that they were, if I had said so I would have been scolded for being ‘unpatriotic.’ Those were terrible times.” But as he clapped his hands to the beat he seemed nostalgic. With their sensory elements, perhaps songs easily become part of a person.

Mr. Nishimura, who was 1.7 km from the hypocenter at the time of the atomic bombing, was badly burned. His homeroom teacher from his days at a national school came to his home to see him. When he told her he was in so much pain that he wanted to die, she slapped him and said, “Think about how you can live your life doing something on behalf of those who died.”

From his teacher who valued life Mr. Nakamura gained the strength to go on living. “I want young people to know that Japan went down the wrong path in the 1930s and ’40s, when people thought dying in the war was the right thing to do,” Mr. Nakamura said.

I realized that war is more than just battlefields, the A-bombing and air raids. The society in which children had to learn war songs was part of the war as well. That must never happen again. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 14)

(Originally published on September 24, 2015)

Junior writers’ postscripts

From my perspective as a high school student, wartime children’s literature was more difficult to read than the children’s stories of the present day. Of course, I was surprised by the content of books on the war and the military, but I hadn’t realized children read such complicated prose before the war. These days, children spend more time playing with electronic devices than reading. Perhaps for that reason they can no longer read difficult Chinese characters. I felt children today must make more time to read books. (Shino Taniguchi)

I had assumed that publications issued during the war were full of war-related content. It was frightening how common it was to intersperse material on pleasant subjects with hidden references to the war in a way that made these references difficult to detect. I want to write my articles keeping in mind that how people interpret what they read and how things are expressed vary from person to person. (Nanase Shode)

It was my first visit to the Kyoto International Manga Museum, and I was overwhelmed by the shelves and shelves of manga. I didn’t think there were many comic books from the past, but the 15 volumes we looked at were in excellent condition. I was even more surprised by that. I’d like to go back to the museum with my family and explain to them that there are manga from various eras. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi)