Former A-bomb hypocenter district restored in computer-animated film

Sep. 30, 2010

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which today attracts visitors from throughout the world, was once the site of the city's liveliest district, an area of homes and workplaces. But the atomic bomb obliterated this whole district in an instant.

Sixty-five years have passed since the atomic bombing. A documentary film entitled "Message from Hiroshima: What was Lost in the Bombing" has now been completed. The film restores the townscape, and the daily lives of its residents, in detail via computer animation. Incorporating the recorded testimonies of former residents, too, the film entrusts the next generation with the task of handing down the memories of that time.

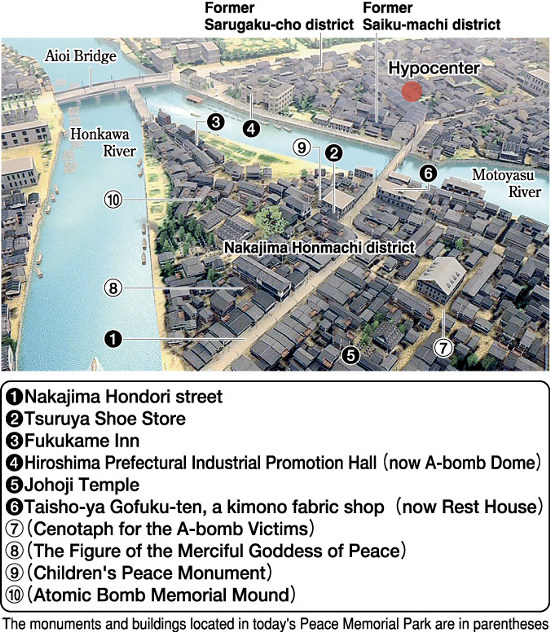

The Film Production Committee for the Restoration of Peace Memorial Park, a group composed of industry, academia, and government participation and supervised by the Knack Images Production Center, spent three years creating the film. The film is set in and around the former Nakajima Honmachi district near the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. The committee has produced a high-definition film of 60 minutes in length.

The former Nakajima Honmachi district covered the delta north of where the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims now stands in Peace Memorial Park, and a large number of residents of the district fell prey to the blast. A monument on which the names of 438 A-bomb victims from the area are inscribed stands in the park by the side of the "Figure of the Merciful Goddess of Peace," a memorial for the residents.

The film production committee has restored the appearance of 50 buildings in the film, basing its depictions on interviews with 60 surviving residents and such materials as photos from the time. A group from the USC School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, which lent its support to the project, took charge of restoring the inside of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now, the Atomic Bomb Dome).

Masaaki Tanabe, 72, the president of a film production company, spearheaded the project. Mr. Tanabe was born and raised in the former Sarugaku-cho area, where the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was located. Mr. Tanabe lost his parents and his younger brother in the bombing.

Since 1997, Mr. Tanabe has, using computer animation, faithfully restored the townscapes of the former Sarugaku-cho district and the former Saiku-machi district, the latter of which was just south of Sarugaku-cho and located beneath the explosion of the atomic bomb. On this occasion, Mr. Tanabe expanded the area for restoration to the former Nakajima Honmachi district, which was just west of Sarugaku-cho across the Motoyasu River. The latest effort is the culmination of his quest to reproduce "the communities obliterated by the atomic bombing."

What made you restore the townscape of the former Nakajima Honmachi district through the use of computer animation?

I showed a computer-animated film that featured the neighborhood of the A-bomb Dome, or the former Sarugaku-cho and the former Saiku-machi, at U.N. headquarters in New York in the spring of 2007. The local media then told me it was good that civilians didn't fall victim to the atomic bombing as the vicinity of the hypocenter had been a park. The comment inspired me to pursue this project.

It's surprising, but few people are aware that the area was once a bustling shopping district and that people were living there. As someone who was born in the area located beneath the explosion of the atomic bomb and an A-bomb survivor, I felt a sense of mission in "restoring" the appearance of these communities and passing this on to the next generation while people who remember those days are still alive.

What did you consider important in the making of the film?

In May of this year, at U.N. headquarters and three universities in the United States, I screened a 30-minute version of the film that was a shortened version of our work in progress. I then received a request that the film also describe the later lives of the A-bomb survivors. This request has served as the inspiration in producing the 60-minute film that conveys a powerful message. We put a lot of thought in the viewpoint involving what the atomic bombing brought to the later lives of survivors.

How would you like the film to be used?

The remains of A-bomb victims are still buried in heaps under Peace Memorial Park. I hope that the film will be used as teaching material in classes across the world so that people can learn why the neighborhood was transformed into a park and they can realize what was lost in the atomic bombing. We will complete the English version of the film as early as this year.

Profile

Masaaki Tanabe

Mr. Tanabe was born in the former Sarugaku-cho, where the A-bomb Dome now stands. He lost his parents and younger brother due to the atomic bombing. Mr. Tanabe was evacuated to Takamizu village in Yamaguchi Prefecture (now, the city of Shunan). He entered the city of Hiroshima on August 8 to look for his family and was exposed to the residual radiation of the atomic bomb. Mr. Tanabe lives in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima.

My family ran the "Tsuruya Shoe Shop" around where the Children's Peace Monument now stands. Colorful clog thongs were displayed behind the counter at which my parents used to sit. I would be fascinated by geisha girls who were choosing a clog thong. Taishoya Kimono Shop, which sold fabric for kimono and is now used as the "Rest House," was across the street. I was harshly scolded when I played hide-and-seek and hid under a kimono for sale in the shop.

In 1945, I found work and went to the former Manchuria in northeastern China. My parents were forced to allow their shop to be demolished to create a fire lane and my family moved to the Senda-machi district. When I came back to Hiroshima a year after the war had ended, I found that my old neighborhood had changed completely.

In the old days, Nakajima Hondori street, with its street lamps that were shaped like lily-of-the-valley flowers, was crowded with so many pedestrians that their shoulders practically rubbed up against one another. Whenever I recall such scenes, I feel nostalgic. I want to show the computer-animated film to my grandchildren and tell them, "The community your Grandpa lived in was so full of life."

My parents ran "Fukukame," a Japanese-style inn that served meals, which was also our home. Rickshaws would stop in front of the inn and geisha girls would come and go. The inn also boasted a tatami-mat room that afforded a view of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. I also remember the fantastic sight of rental boats floating on the Motoyasu River with their glowing lanterns. The computer-animated film has restored the townscape of those good old days. After the Pacific War began, the area gradually lost its vigor. Goods began to be distributed through the rationing system, and we had a difficult life.

On August 6, I escaped death in the atomic bombing, as I had already left home to work as a mobilized student. But I lost six members of my family, including my parents and grandparents. Because Peace Memorial Park was constructed on earth piled over the district that had been razed to the ground, the remains of my family would be found if the area was excavated. Even when the cherry blossoms are blooming, I never feel like I can enjoy the flowers in the park.

Johoji Temple, where my family lived, was located just west of where the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims now stands. The temple had a main hall, the priests' living quarters, and graveyard, among other things. It also played a role something like a cultural center where local residents gathered and enjoyed tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and other activities. The temple grounds were also a playground for children to play tag and "menko," a game of hurling a thick card down to the ground in order to flip over the card of an opponent.

I was evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture in a group of other children in April 1945. I lost my parents and older sister in the atomic bombing. When I got off at Hiroshima station 40 days after the bombing, I was staggered by the burnt ruins of the city, stretching as far as the eye could see. Nothing but rubble remained of the temple. Even the gravestones had been strewn to pieces.

It must be difficult to imagine the once-lively area, which was transformed into Peace Memorial Park, and the devastation wrought by the atomic bombing. However, that area is where our old neighborhood stood. I miss it, and all the more because I lost it.

(Originally published on Sept. 24, 2010)

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which today attracts visitors from throughout the world, was once the site of the city's liveliest district, an area of homes and workplaces. But the atomic bomb obliterated this whole district in an instant.

Sixty-five years have passed since the atomic bombing. A documentary film entitled "Message from Hiroshima: What was Lost in the Bombing" has now been completed. The film restores the townscape, and the daily lives of its residents, in detail via computer animation. Incorporating the recorded testimonies of former residents, too, the film entrusts the next generation with the task of handing down the memories of that time.

The Film Production Committee for the Restoration of Peace Memorial Park, a group composed of industry, academia, and government participation and supervised by the Knack Images Production Center, spent three years creating the film. The film is set in and around the former Nakajima Honmachi district near the hypocenter of the atomic bombing. The committee has produced a high-definition film of 60 minutes in length.

The former Nakajima Honmachi district covered the delta north of where the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims now stands in Peace Memorial Park, and a large number of residents of the district fell prey to the blast. A monument on which the names of 438 A-bomb victims from the area are inscribed stands in the park by the side of the "Figure of the Merciful Goddess of Peace," a memorial for the residents.

The film production committee has restored the appearance of 50 buildings in the film, basing its depictions on interviews with 60 surviving residents and such materials as photos from the time. A group from the USC School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, which lent its support to the project, took charge of restoring the inside of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now, the Atomic Bomb Dome).

Masaaki Tanabe, 72, the president of a film production company, spearheaded the project. Mr. Tanabe was born and raised in the former Sarugaku-cho area, where the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was located. Mr. Tanabe lost his parents and his younger brother in the bombing.

Since 1997, Mr. Tanabe has, using computer animation, faithfully restored the townscapes of the former Sarugaku-cho district and the former Saiku-machi district, the latter of which was just south of Sarugaku-cho and located beneath the explosion of the atomic bomb. On this occasion, Mr. Tanabe expanded the area for restoration to the former Nakajima Honmachi district, which was just west of Sarugaku-cho across the Motoyasu River. The latest effort is the culmination of his quest to reproduce "the communities obliterated by the atomic bombing."

Interview with Masaaki Tanabe, 72, leader of the project: The responsibility of A-bomb survivors

What made you restore the townscape of the former Nakajima Honmachi district through the use of computer animation?

I showed a computer-animated film that featured the neighborhood of the A-bomb Dome, or the former Sarugaku-cho and the former Saiku-machi, at U.N. headquarters in New York in the spring of 2007. The local media then told me it was good that civilians didn't fall victim to the atomic bombing as the vicinity of the hypocenter had been a park. The comment inspired me to pursue this project.

It's surprising, but few people are aware that the area was once a bustling shopping district and that people were living there. As someone who was born in the area located beneath the explosion of the atomic bomb and an A-bomb survivor, I felt a sense of mission in "restoring" the appearance of these communities and passing this on to the next generation while people who remember those days are still alive.

What did you consider important in the making of the film?

In May of this year, at U.N. headquarters and three universities in the United States, I screened a 30-minute version of the film that was a shortened version of our work in progress. I then received a request that the film also describe the later lives of the A-bomb survivors. This request has served as the inspiration in producing the 60-minute film that conveys a powerful message. We put a lot of thought in the viewpoint involving what the atomic bombing brought to the later lives of survivors.

How would you like the film to be used?

The remains of A-bomb victims are still buried in heaps under Peace Memorial Park. I hope that the film will be used as teaching material in classes across the world so that people can learn why the neighborhood was transformed into a park and they can realize what was lost in the atomic bombing. We will complete the English version of the film as early as this year.

Profile

Masaaki Tanabe

Mr. Tanabe was born in the former Sarugaku-cho, where the A-bomb Dome now stands. He lost his parents and younger brother due to the atomic bombing. Mr. Tanabe was evacuated to Takamizu village in Yamaguchi Prefecture (now, the city of Shunan). He entered the city of Hiroshima on August 8 to look for his family and was exposed to the residual radiation of the atomic bomb. Mr. Tanabe lives in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima.

Akinori Ueda, 81: "I want to tell my grandchildren that it was full of life"

My family ran the "Tsuruya Shoe Shop" around where the Children's Peace Monument now stands. Colorful clog thongs were displayed behind the counter at which my parents used to sit. I would be fascinated by geisha girls who were choosing a clog thong. Taishoya Kimono Shop, which sold fabric for kimono and is now used as the "Rest House," was across the street. I was harshly scolded when I played hide-and-seek and hid under a kimono for sale in the shop.

In 1945, I found work and went to the former Manchuria in northeastern China. My parents were forced to allow their shop to be demolished to create a fire lane and my family moved to the Senda-machi district. When I came back to Hiroshima a year after the war had ended, I found that my old neighborhood had changed completely.

In the old days, Nakajima Hondori street, with its street lamps that were shaped like lily-of-the-valley flowers, was crowded with so many pedestrians that their shoulders practically rubbed up against one another. Whenever I recall such scenes, I feel nostalgic. I want to show the computer-animated film to my grandchildren and tell them, "The community your Grandpa lived in was so full of life."

Kazuo Fukushima, 78: "The boats floating on the river were fantastic"

My parents ran "Fukukame," a Japanese-style inn that served meals, which was also our home. Rickshaws would stop in front of the inn and geisha girls would come and go. The inn also boasted a tatami-mat room that afforded a view of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. I also remember the fantastic sight of rental boats floating on the Motoyasu River with their glowing lanterns. The computer-animated film has restored the townscape of those good old days. After the Pacific War began, the area gradually lost its vigor. Goods began to be distributed through the rationing system, and we had a difficult life.

On August 6, I escaped death in the atomic bombing, as I had already left home to work as a mobilized student. But I lost six members of my family, including my parents and grandparents. Because Peace Memorial Park was constructed on earth piled over the district that had been razed to the ground, the remains of my family would be found if the area was excavated. Even when the cherry blossoms are blooming, I never feel like I can enjoy the flowers in the park.

Ryoga Suwa, 77: "I was deeply moved by the film, all the more for what I lost"

Johoji Temple, where my family lived, was located just west of where the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims now stands. The temple had a main hall, the priests' living quarters, and graveyard, among other things. It also played a role something like a cultural center where local residents gathered and enjoyed tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and other activities. The temple grounds were also a playground for children to play tag and "menko," a game of hurling a thick card down to the ground in order to flip over the card of an opponent.

I was evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture in a group of other children in April 1945. I lost my parents and older sister in the atomic bombing. When I got off at Hiroshima station 40 days after the bombing, I was staggered by the burnt ruins of the city, stretching as far as the eye could see. Nothing but rubble remained of the temple. Even the gravestones had been strewn to pieces.

It must be difficult to imagine the once-lively area, which was transformed into Peace Memorial Park, and the devastation wrought by the atomic bombing. However, that area is where our old neighborhood stood. I miss it, and all the more because I lost it.

(Originally published on Sept. 24, 2010)