Peace education today at Hiroshima’s junior high schools

Apr. 28, 2009

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

With the start of the new school year, the Chugoku Shimbun took a look at the state of peace education at junior high schools in Hiroshima City. As the atomic bombing recedes into the past, it is becoming more and more difficult to conduct classes in which students hear directly from survivors of the bombing. And with the emphasis on academic achievement, there is a tendency to cut the time allotted to peace education. In addition, teachers who lead peace education efforts were born after the war. For these reasons, passing on the know-how necessary to teach students about the atomic bombing and peace education is now a compelling challenge.

Booklet describing A-bombing experiences passed down

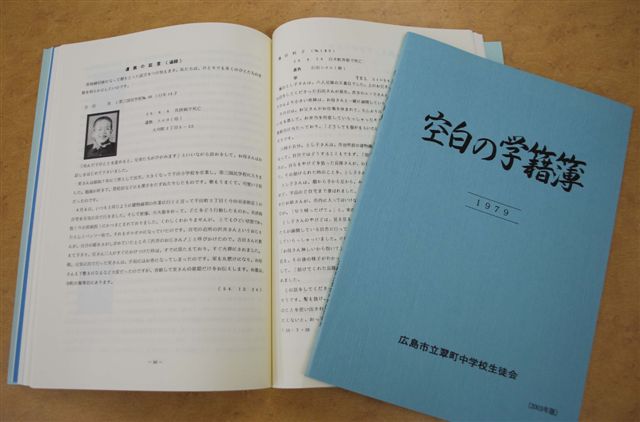

Upon assuming the post of principal of Midorimachi Junior High School this month, Kenji Naka, 54, received a booklet titled Kuhaku no Gakusekibo ("The Blank School Register") from his predecessor. He has begun dipping into the blue booklet, which the school’s principals have been reading for more than 20 years.

According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb Disaster, 143 students from Midorimachi Junior High School, then called Elementary School No. 3, were killed in the atomic bombing as they worked to demolish buildings in the Zakoba-cho district (now, the Kokutaiji-machi district). Kuhaku no Gakusekibo provides accounts of the experiences of their families and teachers.

Starting in 1977, the student council visited the homes of the families of students who were killed in the bombing and tape-recorded their stories. Addressing themselves to the students, all of those interviewed expressed the hope that children would never again meet the same fate.

Here is an excerpt from one account: “Satoko didn’t give up. She walked all the way home from Zakoba-cho across the hot, burned ground with the bones in her feet exposed. Her mother and father were at her side when she died later that day.”

This booklet is still used as a supplementary reader for peace education at Midorimachi Junior High School. Every July the students read it aloud during their homeroom period and learn about the students who conducted the interviews through a program produced by a local television station in 1977.

The school’s current teachers share the belief that they have an obligation to pass on the contents of the booklet to future generations and are opposed to eliminating peace education.

But most of the junior high schools in Hiroshima say that it has become more difficult to make time for peace education.

For example, these days only first-year students at Kokutaiji Junior High School have peace education classes. The school’s principal, Tatsuhiko Hamamura, 56, said it was a tough decision but that the school’s top priority was to make time for compulsory subjects. At the same time he said he believes schools have an increasingly important role to play as children lose the opportunity to hear about the atomic bombing from family members. So since last summer all of the school’s students have been required to participate in the ceremonies commemorating the atomic bombing that are conducted at the elementary schools from which they graduated.

Meanwhile, Hisaharu Matsui, 55, a teacher of Ozu Junior High School said, “Focusing on the decline in peace education is counterproductive.” As a member of the Peace Education Committee of the city’s teachers’ union, which has conducted a survey of peace education at the city’s elementary and junior high schools since 1982, he believes many schools and teachers are still making an effort to maintain their peace education programs.

This year Eba Junior High School has allotted about 15 hours for peace education to students in all three grades. For the first time this year, second-year students will take part in field work using the online resource "Atomic Bombing in Pictures," a collection of pictures drawn by survivors.

Teams of students will visit locations depicted in these pictures and interview people involved in the rebuilding of those areas. Kimihiko Watanabe, 56, the teacher who came up with the idea for the class, said, “I want the students to not only learn about what happened in the past but also to be aware of the efforts that were made to rebuild the city and to see the strength of the message of Hiroshima in a fresh light.” Mr. Watanabe, through sharing information with four teachers from other schools over the past four years, formulated the lesson plan.

With the aging of the atomic bomb survivors, it has become more difficult to hear first-person accounts of the bombing. Consequently, in some cases, the focus of peace education has begun to shift to other areas such as disseminating a message of peace to the world.

In March, all of the soon-to-be second-year students at Misuzugaoka Junior High School sent paper cranes that they had folded to junior high school students in Nuremberg, Germany. On the cranes they wrote messages in German calling for peace. Masakiyo Hasegawa, 13, said that his grandfather talked about his experiences of the atomic bombing to him only once. “Grandpa was spared because he didn’t go to school that day, but many of his classmates were killed,” he said. On his crane he wrote, “The most important thing is peace.”

Masao Narasaki, 47, the school’s vice principal, said, “I would like the children of Hiroshima to do even more to spread the message of peace.” The letter that arrived from Germany this month had “thank you” and other messages written on it in English. The students translated the letter in their English class and plan to send a reply in English.

School board provides materials for city’s schools

According to a survey conducted by the Hiroshima Municipal Board of Education in 2005, 67.6% of junior high school students in the city could correctly give the year and date of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, down from 74.7% 10 years earlier. On the other hand, the number of students who said they felt no desire to do something to help bring about peace in the future increased during the same period from 11.8% to 16.1%.

In many cases peace education is offered during the class time allotted for “integrated learning.” The Education Ministry’s curriculum guidelines provide several examples of subjects that may be covered in integrated learning such as work experience, the environment, and welfare, but peace education is not included.

Meanwhile the teachers who survived the atomic bombing have retired, and it is difficult to pass on their knowledge about peace education to current teachers. Also, as the atomic bomb survivors grow old, there are fewer opportunities to invite those who live in the neighborhood to schools to tell students about their experiences.

This school year the school board expanded the trial introduction of its so-called “Hiroshima-style curriculum,” a program that makes use of the Internet, newspapers, and other materials to enhance students’ ability to utilize language and mathematics, to all of the city’s junior high schools. Teachers have reportedly complained that this has made it even more difficult to conduct peace education.

According to Teacher Supervisory Division II of the school board’s School Education Department, “Some facets of Hiroshima’s peace education are the product of individual teachers’ efforts, but thinking of the future, the school board must offer its support.”

In 2006, the school board distributed “Instructional Materials for Peace Education” to all principals of elementary and junior high schools in the city, and since last fall “Goals of Peace Education” have been posted on the school board’s website. These goals are centered on passing down the atomic bombing experience and spreading the message of peace. In addition, they have begun collecting footage of A-bomb survivors sharing their experiences with schoolchildren and introducing possible overseas partners for exchange activities related to peace.

How do you regard the current state of peace education in Hiroshima?

Peace education became common in elementary and junior high schools in the 1970s. In his peace declaration in 1971, then Mayor Setsuo Yamada said that “education for peace should be promoted with vigour and cogency throughout the world. This should be the absolute way to avoid the recurrence of the tragedy of Hiroshima.” As a result, every school made an effort to set aside time for peace education. Efforts like Midorimachi’s Kuhaku no Gakusekibo are assets to the city, but now schools are having difficulty finding time for compulsory subjects, and peace education is being squeezed out.

Some people have suggested that the stricter curriculum put forth by the Ministry of Education in 1998 weakened peace education.

I think it had a major impact. Even in Hiroshima, teachers were daunted, but we can’t blame everything on the stricter curriculum. I think that in some respects Hiroshima-style peace education, which involves learning about the tragedy of the atomic bombing and conveying the importance of peace, has reached a turning point. With peace education in a rut, it demoralizes not only students but teachers as well. The peace education curriculum needs to be reviewed.

What kind of classes do you think we should have?

How can teachers who did not experience the war, pass on the atomic bombing experience to children who were born in the last 15 years? Teachers must continue to seek an answer to this question. You can show students a photograph that was taken immediately after the war and ask them why it shows many female students. In this way, you could provide an opportunity for students to look at the issue of mobilized students from their point of view.

How about asking young teachers and the parents of elementary and junior high school students for suggestions for a new kind of peace education? Issues like poverty and the environment as well as current conflicts like the Iraq war and Israel’s attacks on Gaza should be included.

What is needed to carry on and expand peace education?

First of all, a system whereby veteran teachers can pass on their know-how to younger teachers must be created. Younger teachers should be provided with such information as the kinds of teaching methods and materials that can hold the interest of today’s students. It is difficult for these younger teachers to acquire good experience unless they have a chance to work at a school where the principal and other, more experienced teachers are enthusiastic about peace education. We need a mechanism to expand ties between schools and between teachers and to allow information to be shared.

Many classroom teachers say they have never seen the school board’s “Instructional Materials for Peace Education.” The school board must make an effort to ensure that not only school principals but also classroom teachers are aware of the importance of peace education.

Bringing up young people who will build a peaceful world is the foundation of education. We need to reaffirm the significance of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima with an awareness of the attention focused on Hiroshima from outside. If we use a little creativity, we can find ways to introduce the subject of peace into Japanese, social studies, and foreign language classes.

Yoshie Funahashi

Native of Nagoya. Specializes in the study of the history of social thought. Chairperson of the Association for Counselors for Hibakusha. Author of Hyuumu to Ningen no Kagaku ("Hume and Human Science") and other titles.

(Originally published April 20, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

With the start of the new school year, the Chugoku Shimbun took a look at the state of peace education at junior high schools in Hiroshima City. As the atomic bombing recedes into the past, it is becoming more and more difficult to conduct classes in which students hear directly from survivors of the bombing. And with the emphasis on academic achievement, there is a tendency to cut the time allotted to peace education. In addition, teachers who lead peace education efforts were born after the war. For these reasons, passing on the know-how necessary to teach students about the atomic bombing and peace education is now a compelling challenge.

Booklet describing A-bombing experiences passed down

Upon assuming the post of principal of Midorimachi Junior High School this month, Kenji Naka, 54, received a booklet titled Kuhaku no Gakusekibo ("The Blank School Register") from his predecessor. He has begun dipping into the blue booklet, which the school’s principals have been reading for more than 20 years.

According to the Record of the Hiroshima A-bomb Disaster, 143 students from Midorimachi Junior High School, then called Elementary School No. 3, were killed in the atomic bombing as they worked to demolish buildings in the Zakoba-cho district (now, the Kokutaiji-machi district). Kuhaku no Gakusekibo provides accounts of the experiences of their families and teachers.

Starting in 1977, the student council visited the homes of the families of students who were killed in the bombing and tape-recorded their stories. Addressing themselves to the students, all of those interviewed expressed the hope that children would never again meet the same fate.

Here is an excerpt from one account: “Satoko didn’t give up. She walked all the way home from Zakoba-cho across the hot, burned ground with the bones in her feet exposed. Her mother and father were at her side when she died later that day.”

This booklet is still used as a supplementary reader for peace education at Midorimachi Junior High School. Every July the students read it aloud during their homeroom period and learn about the students who conducted the interviews through a program produced by a local television station in 1977.

The school’s current teachers share the belief that they have an obligation to pass on the contents of the booklet to future generations and are opposed to eliminating peace education.

But most of the junior high schools in Hiroshima say that it has become more difficult to make time for peace education.

For example, these days only first-year students at Kokutaiji Junior High School have peace education classes. The school’s principal, Tatsuhiko Hamamura, 56, said it was a tough decision but that the school’s top priority was to make time for compulsory subjects. At the same time he said he believes schools have an increasingly important role to play as children lose the opportunity to hear about the atomic bombing from family members. So since last summer all of the school’s students have been required to participate in the ceremonies commemorating the atomic bombing that are conducted at the elementary schools from which they graduated.

Meanwhile, Hisaharu Matsui, 55, a teacher of Ozu Junior High School said, “Focusing on the decline in peace education is counterproductive.” As a member of the Peace Education Committee of the city’s teachers’ union, which has conducted a survey of peace education at the city’s elementary and junior high schools since 1982, he believes many schools and teachers are still making an effort to maintain their peace education programs.

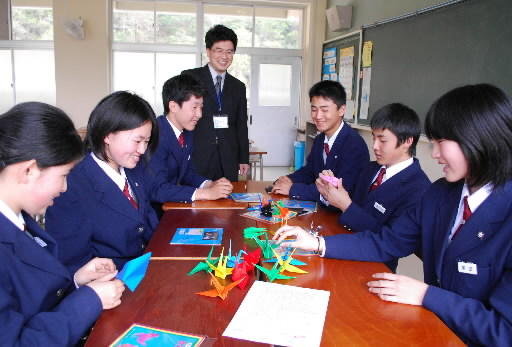

This year Eba Junior High School has allotted about 15 hours for peace education to students in all three grades. For the first time this year, second-year students will take part in field work using the online resource "Atomic Bombing in Pictures," a collection of pictures drawn by survivors.

Teams of students will visit locations depicted in these pictures and interview people involved in the rebuilding of those areas. Kimihiko Watanabe, 56, the teacher who came up with the idea for the class, said, “I want the students to not only learn about what happened in the past but also to be aware of the efforts that were made to rebuild the city and to see the strength of the message of Hiroshima in a fresh light.” Mr. Watanabe, through sharing information with four teachers from other schools over the past four years, formulated the lesson plan.

With the aging of the atomic bomb survivors, it has become more difficult to hear first-person accounts of the bombing. Consequently, in some cases, the focus of peace education has begun to shift to other areas such as disseminating a message of peace to the world.

In March, all of the soon-to-be second-year students at Misuzugaoka Junior High School sent paper cranes that they had folded to junior high school students in Nuremberg, Germany. On the cranes they wrote messages in German calling for peace. Masakiyo Hasegawa, 13, said that his grandfather talked about his experiences of the atomic bombing to him only once. “Grandpa was spared because he didn’t go to school that day, but many of his classmates were killed,” he said. On his crane he wrote, “The most important thing is peace.”

Masao Narasaki, 47, the school’s vice principal, said, “I would like the children of Hiroshima to do even more to spread the message of peace.” The letter that arrived from Germany this month had “thank you” and other messages written on it in English. The students translated the letter in their English class and plan to send a reply in English.

School board provides materials for city’s schools

According to a survey conducted by the Hiroshima Municipal Board of Education in 2005, 67.6% of junior high school students in the city could correctly give the year and date of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, down from 74.7% 10 years earlier. On the other hand, the number of students who said they felt no desire to do something to help bring about peace in the future increased during the same period from 11.8% to 16.1%.

In many cases peace education is offered during the class time allotted for “integrated learning.” The Education Ministry’s curriculum guidelines provide several examples of subjects that may be covered in integrated learning such as work experience, the environment, and welfare, but peace education is not included.

Meanwhile the teachers who survived the atomic bombing have retired, and it is difficult to pass on their knowledge about peace education to current teachers. Also, as the atomic bomb survivors grow old, there are fewer opportunities to invite those who live in the neighborhood to schools to tell students about their experiences.

This school year the school board expanded the trial introduction of its so-called “Hiroshima-style curriculum,” a program that makes use of the Internet, newspapers, and other materials to enhance students’ ability to utilize language and mathematics, to all of the city’s junior high schools. Teachers have reportedly complained that this has made it even more difficult to conduct peace education.

According to Teacher Supervisory Division II of the school board’s School Education Department, “Some facets of Hiroshima’s peace education are the product of individual teachers’ efforts, but thinking of the future, the school board must offer its support.”

In 2006, the school board distributed “Instructional Materials for Peace Education” to all principals of elementary and junior high schools in the city, and since last fall “Goals of Peace Education” have been posted on the school board’s website. These goals are centered on passing down the atomic bombing experience and spreading the message of peace. In addition, they have begun collecting footage of A-bomb survivors sharing their experiences with schoolchildren and introducing possible overseas partners for exchange activities related to peace.

Schools must share know-how: Interview with Yoshie Funahashi, Professor Emeritus of Hiroshima University

How do you regard the current state of peace education in Hiroshima?

Peace education became common in elementary and junior high schools in the 1970s. In his peace declaration in 1971, then Mayor Setsuo Yamada said that “education for peace should be promoted with vigour and cogency throughout the world. This should be the absolute way to avoid the recurrence of the tragedy of Hiroshima.” As a result, every school made an effort to set aside time for peace education. Efforts like Midorimachi’s Kuhaku no Gakusekibo are assets to the city, but now schools are having difficulty finding time for compulsory subjects, and peace education is being squeezed out.

Some people have suggested that the stricter curriculum put forth by the Ministry of Education in 1998 weakened peace education.

I think it had a major impact. Even in Hiroshima, teachers were daunted, but we can’t blame everything on the stricter curriculum. I think that in some respects Hiroshima-style peace education, which involves learning about the tragedy of the atomic bombing and conveying the importance of peace, has reached a turning point. With peace education in a rut, it demoralizes not only students but teachers as well. The peace education curriculum needs to be reviewed.

What kind of classes do you think we should have?

How can teachers who did not experience the war, pass on the atomic bombing experience to children who were born in the last 15 years? Teachers must continue to seek an answer to this question. You can show students a photograph that was taken immediately after the war and ask them why it shows many female students. In this way, you could provide an opportunity for students to look at the issue of mobilized students from their point of view.

How about asking young teachers and the parents of elementary and junior high school students for suggestions for a new kind of peace education? Issues like poverty and the environment as well as current conflicts like the Iraq war and Israel’s attacks on Gaza should be included.

What is needed to carry on and expand peace education?

First of all, a system whereby veteran teachers can pass on their know-how to younger teachers must be created. Younger teachers should be provided with such information as the kinds of teaching methods and materials that can hold the interest of today’s students. It is difficult for these younger teachers to acquire good experience unless they have a chance to work at a school where the principal and other, more experienced teachers are enthusiastic about peace education. We need a mechanism to expand ties between schools and between teachers and to allow information to be shared.

Many classroom teachers say they have never seen the school board’s “Instructional Materials for Peace Education.” The school board must make an effort to ensure that not only school principals but also classroom teachers are aware of the importance of peace education.

Bringing up young people who will build a peaceful world is the foundation of education. We need to reaffirm the significance of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima with an awareness of the attention focused on Hiroshima from outside. If we use a little creativity, we can find ways to introduce the subject of peace into Japanese, social studies, and foreign language classes.

Yoshie Funahashi

Native of Nagoya. Specializes in the study of the history of social thought. Chairperson of the Association for Counselors for Hibakusha. Author of Hyuumu to Ningen no Kagaku ("Hume and Human Science") and other titles.

(Originally published April 20, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.