Hiroshima Memo: The vow of the inscription on the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims

Aug. 19, 2011

by Akira Tashiro, Executive Director of the Hiroshima Peace Media Center

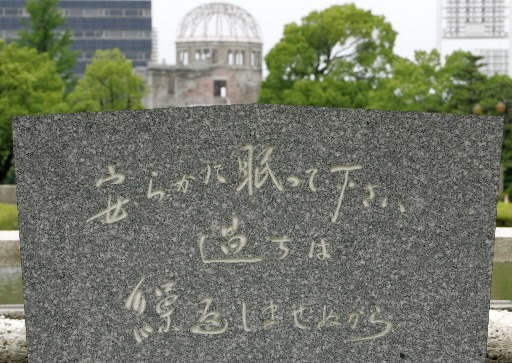

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is located near my office. When I want to stretch my legs, the park is where I go. As I walk through the park, I often stop at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims to read the inscription on the cenotaph.

“Let all the souls here rest in peace; for we shall not repeat the evil.”

The inscription signifies a vow that each person standing at the cenotaph makes for the victims of the atomic bombing. For me, it is a spot where I can ask myself whether or not my work is contributing to this cause.

In early June, the author Haruki Murakami attended an award presentation ceremony in Barcelona, Spain. Mr. Murakami cited the inscription during his acceptance speech and said, “We must inscribe the words on our hearts once again.” He also referred to the radiation contamination wrought by the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, and the fact that the small, quake-prone country of Japan has the third largest number of nuclear power plants in the world. “We, the Japanese, should have kept saying 'No' to nuclear power,” Mr. Murakami said.

Antipathy toward nuclear power had been instilled in the minds of the Japanese people as a result of the nation's experience of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his speech, Mr. Murakami stressed that the Japanese “should have made developing energy sources without using nuclear power the core proposition in the post-war path of Japan,” by “retaining uncompromisingly” that antipathy toward nuclear power.

Nuclear weapons and nuclear power generation are the same in the sense that both utilize the same hazardous nuclear materials. Mr. Murakami's convictions arise from the recognition that the military use and the peaceful use of these nuclear materials “share the same roots.”

However, people's perceptions of nuclear power differed in the mid-1950s when U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower proclaimed the idea of “Atoms for Peace” at the United Nations in 1953, and Japan began to take steps toward bringing nuclear power to this nation. Many of the A-bomb survivors who had suffered the effects of radiation on their bodies from their firsthand experience, as well as nuclear scientists, held a positive opinion of the peaceful use of nuclear power, seeing it as an “ideal source of energy” that could sustain humanity into the future. Indeed, the U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954, which showered the Japanese crew of tuna fishing boats with radioactive fallout and resulted in the contamination of large catches of tuna fish, triggered a nationwide movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs, but did not lead to opposition against the introduction of nuclear power in Japan.

At the time, the Japanese people were beguiled by the nation's economic recovery following their defeat in World War II, as well as the allure of becoming a society of scientific and technological prowess. They believed that the power behind the atomic bombs, which had unleashed an annihilating force on the nation, could now contribute to “the wealth and welfare of the people” if humanity would harness and utilize nuclear energy with a firm moral hand. In part, this idea was bred by an information campaign pursued by the United States, which sought to market its nuclear energy technology to Japan and ease anti-U.S. sentiment that had mounted in the wake of its nuclear tests. However, it can also said that the Japanese people held a simplistic view of nuclear power back then.

Less than one year after Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum opened its doors in August 1955, the museum held a large-scale exhibition on the “peaceful use of atomic energy.” In line with the “safety myth” of nuclear power plants--the idea that they would never produce a radiation-related accident--the fact that A-bomb survivors were suffering from the lingering effects of radiation released by the atomic bombs was treated as a “different aspect” of nuclear weapons.

It is fortunate indeed that human beings have managed to avoid nuclear warfare since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But as a consequence of the nuclear arms race, the spread of nuclear energy, and the use of depleted uranium shells, the invisible threat of radiation continues to plague us to this day. Scores of new hibakusha, or radiation sufferers, and radiation-contaminated areas have been created across the world.

In the late 1980s, I myself came to learn the gravity of this situation. Through my work as a journalist, I encountered the horrific reality of the new hibakusha that are being produced by the development of nuclear weapons and accidents at nuclear power plants, among other causes. Since that time I have continued my investigation of this peril. So that “the evil” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will not be repeated, it is not enough to end war and eliminate nuclear weapons from the earth. We must also avoid producing further hibakusha.

But the disaster at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant means that the people of the A-bombed nation of Japan have already committed this evil themselves.

Late as the time may be, we must bring together all the expertise, technology, capital, and political will at our disposal to break away from the nation's reliance on nuclear energy. This, I believe, is the lesson that must be learned from Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Bikini, and now the accident in Fukushima. I believe, too, that this new path would enable us to at last live up to the inscription found on the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims.

(Originally published on July 22, 2011)

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is located near my office. When I want to stretch my legs, the park is where I go. As I walk through the park, I often stop at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims to read the inscription on the cenotaph.

“Let all the souls here rest in peace; for we shall not repeat the evil.”

The inscription signifies a vow that each person standing at the cenotaph makes for the victims of the atomic bombing. For me, it is a spot where I can ask myself whether or not my work is contributing to this cause.

In early June, the author Haruki Murakami attended an award presentation ceremony in Barcelona, Spain. Mr. Murakami cited the inscription during his acceptance speech and said, “We must inscribe the words on our hearts once again.” He also referred to the radiation contamination wrought by the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, and the fact that the small, quake-prone country of Japan has the third largest number of nuclear power plants in the world. “We, the Japanese, should have kept saying 'No' to nuclear power,” Mr. Murakami said.

Antipathy toward nuclear power had been instilled in the minds of the Japanese people as a result of the nation's experience of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his speech, Mr. Murakami stressed that the Japanese “should have made developing energy sources without using nuclear power the core proposition in the post-war path of Japan,” by “retaining uncompromisingly” that antipathy toward nuclear power.

Nuclear weapons and nuclear power generation are the same in the sense that both utilize the same hazardous nuclear materials. Mr. Murakami's convictions arise from the recognition that the military use and the peaceful use of these nuclear materials “share the same roots.”

However, people's perceptions of nuclear power differed in the mid-1950s when U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower proclaimed the idea of “Atoms for Peace” at the United Nations in 1953, and Japan began to take steps toward bringing nuclear power to this nation. Many of the A-bomb survivors who had suffered the effects of radiation on their bodies from their firsthand experience, as well as nuclear scientists, held a positive opinion of the peaceful use of nuclear power, seeing it as an “ideal source of energy” that could sustain humanity into the future. Indeed, the U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954, which showered the Japanese crew of tuna fishing boats with radioactive fallout and resulted in the contamination of large catches of tuna fish, triggered a nationwide movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs, but did not lead to opposition against the introduction of nuclear power in Japan.

At the time, the Japanese people were beguiled by the nation's economic recovery following their defeat in World War II, as well as the allure of becoming a society of scientific and technological prowess. They believed that the power behind the atomic bombs, which had unleashed an annihilating force on the nation, could now contribute to “the wealth and welfare of the people” if humanity would harness and utilize nuclear energy with a firm moral hand. In part, this idea was bred by an information campaign pursued by the United States, which sought to market its nuclear energy technology to Japan and ease anti-U.S. sentiment that had mounted in the wake of its nuclear tests. However, it can also said that the Japanese people held a simplistic view of nuclear power back then.

Less than one year after Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum opened its doors in August 1955, the museum held a large-scale exhibition on the “peaceful use of atomic energy.” In line with the “safety myth” of nuclear power plants--the idea that they would never produce a radiation-related accident--the fact that A-bomb survivors were suffering from the lingering effects of radiation released by the atomic bombs was treated as a “different aspect” of nuclear weapons.

It is fortunate indeed that human beings have managed to avoid nuclear warfare since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But as a consequence of the nuclear arms race, the spread of nuclear energy, and the use of depleted uranium shells, the invisible threat of radiation continues to plague us to this day. Scores of new hibakusha, or radiation sufferers, and radiation-contaminated areas have been created across the world.

In the late 1980s, I myself came to learn the gravity of this situation. Through my work as a journalist, I encountered the horrific reality of the new hibakusha that are being produced by the development of nuclear weapons and accidents at nuclear power plants, among other causes. Since that time I have continued my investigation of this peril. So that “the evil” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will not be repeated, it is not enough to end war and eliminate nuclear weapons from the earth. We must also avoid producing further hibakusha.

But the disaster at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant means that the people of the A-bombed nation of Japan have already committed this evil themselves.

Late as the time may be, we must bring together all the expertise, technology, capital, and political will at our disposal to break away from the nation's reliance on nuclear energy. This, I believe, is the lesson that must be learned from Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Bikini, and now the accident in Fukushima. I believe, too, that this new path would enable us to at last live up to the inscription found on the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims.

(Originally published on July 22, 2011)