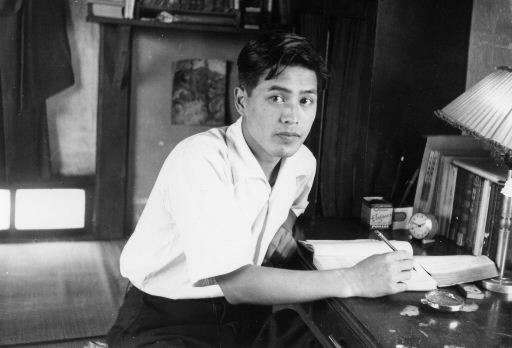

My Life: Interview with former Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka, Part 5

Oct. 14, 2009

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

After returning to Japan from Korea, Mr. Hiraoka graduated from the former Hiroshima High School in 1948, then moved to Tokyo.

I was actively involved in the student movement, or should I say in collecting signatures to support the Stockholm Appeal. I did not join the Communist Party, but I was definitely influenced by the general atmosphere of the times.

As a Hiroshima native, I saw the horror of the atomic bombing and naturally thought that nuclear weapons should not be used again. When the Korean War broke out [in June 1950], I often heard the names of places that were familiar to me over the radio and there were concerns that the United States might again use atomic bombs. Korean residents living in Japan were desperately engaged in the antiwar movement. I felt inspired by them.

The World Peace Council, led by the former Soviet Union, announced an appeal for a total ban on nuclear weapons in March 1950. More than six million signatures to support the appeal were collected in Japan, then occupied by the United States.

In those days, I was busy with editing work. The editor in chief at Yuhikaku Publishing Co., Ltd. was a former Hiroshima High School graduate, and I got a part-time job there. Toshio Hironaka [currently professor emeritus at Tohoku University], who also graduated from the same high school a year before me, was also working there part-time. He asked me to join the present-day University of Tokyo Press [established in March 1951]. This was after the company's forerunner, the Tokyo University Cooperative Publishing Department, published a compilation of writings by student soldiers. This book, titled Kike Wadatumi no Koe (Listen to the Voices from the Sea), was issued in October 1949 and met with much success.

There were four staff members in the editorial section. I was in charge of literature and history books. One of the works by Sho Ishimoda [one of the leading Marxist historians of the time who died in 1986], Rekishi to Minzoku no Hakken (Discovery of History and Ethnicity) is very special to me. Since he delved into the history of ordinary people, I asked him to write for us, but he said he didn't have time. So I searched newspapers and magazines at the National Diet Library for articles he had written and compiled a book largely based on those articles.

The book was published in March 1952 and became very popular among students. In its preface, Mr. Ishimoda expressed his gratitude, saying, "This book would not have been completed without the help of Takashi Hiraoka."

I studied German at Hiroshima High School, so I majored in German literature at Waseda University. I chose Kafka for the theme of my graduation thesis. At that time, not many of his works had been translated into Japanese. I graduated from the university in 1952, when it was very hard to land a job. Even for those who had an education, the only jobs available were those in teaching. I had already quit working for the University of Tokyo Press at the beginning of that year, as it had come to be under the direct control of the university. On top of that, my health wasn't good. My father repeatedly asked me to come back to Hiroshima. So, even though my friends pitied me for leaving Tokyo, I returned to Hiroshima.

(Originally published on October 3, 2009)

Living in Tokyo: Busy in activism and editing

After returning to Japan from Korea, Mr. Hiraoka graduated from the former Hiroshima High School in 1948, then moved to Tokyo.

I was actively involved in the student movement, or should I say in collecting signatures to support the Stockholm Appeal. I did not join the Communist Party, but I was definitely influenced by the general atmosphere of the times.

As a Hiroshima native, I saw the horror of the atomic bombing and naturally thought that nuclear weapons should not be used again. When the Korean War broke out [in June 1950], I often heard the names of places that were familiar to me over the radio and there were concerns that the United States might again use atomic bombs. Korean residents living in Japan were desperately engaged in the antiwar movement. I felt inspired by them.

The World Peace Council, led by the former Soviet Union, announced an appeal for a total ban on nuclear weapons in March 1950. More than six million signatures to support the appeal were collected in Japan, then occupied by the United States.

In those days, I was busy with editing work. The editor in chief at Yuhikaku Publishing Co., Ltd. was a former Hiroshima High School graduate, and I got a part-time job there. Toshio Hironaka [currently professor emeritus at Tohoku University], who also graduated from the same high school a year before me, was also working there part-time. He asked me to join the present-day University of Tokyo Press [established in March 1951]. This was after the company's forerunner, the Tokyo University Cooperative Publishing Department, published a compilation of writings by student soldiers. This book, titled Kike Wadatumi no Koe (Listen to the Voices from the Sea), was issued in October 1949 and met with much success.

There were four staff members in the editorial section. I was in charge of literature and history books. One of the works by Sho Ishimoda [one of the leading Marxist historians of the time who died in 1986], Rekishi to Minzoku no Hakken (Discovery of History and Ethnicity) is very special to me. Since he delved into the history of ordinary people, I asked him to write for us, but he said he didn't have time. So I searched newspapers and magazines at the National Diet Library for articles he had written and compiled a book largely based on those articles.

The book was published in March 1952 and became very popular among students. In its preface, Mr. Ishimoda expressed his gratitude, saying, "This book would not have been completed without the help of Takashi Hiraoka."

I studied German at Hiroshima High School, so I majored in German literature at Waseda University. I chose Kafka for the theme of my graduation thesis. At that time, not many of his works had been translated into Japanese. I graduated from the university in 1952, when it was very hard to land a job. Even for those who had an education, the only jobs available were those in teaching. I had already quit working for the University of Tokyo Press at the beginning of that year, as it had come to be under the direct control of the university. On top of that, my health wasn't good. My father repeatedly asked me to come back to Hiroshima. So, even though my friends pitied me for leaving Tokyo, I returned to Hiroshima.

(Originally published on October 3, 2009)