Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 2)

Apr. 10, 2012

Newspaper's Volunteer Citizens’ Corps wiped out

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Demolition of buildings: Devastation just after mobilization

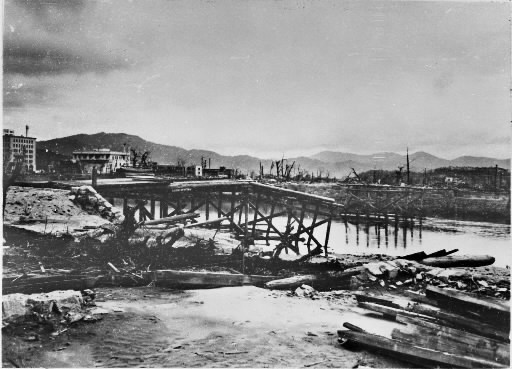

On the morning of August 6, 1945, in the downtown area of the Hiroshima delta, students in their early teens and men and women of all ages who were members of Volunteer Citizens’ Corps organizations were mobilized for the demolition of buildings on the order of the central government. They experienced the atomic bombing with nothing to shield them from its blast, thermal rays or radiation. The members of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps, made up of newspaper and news agency employees in Hiroshima, had gone to the right bank of the Motoyasu River, about 500 meters southwest of the hypocenter, an area that is now on the south side of Peace Memorial Park. In this article the Chugoku Shimbun pursues the story of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps, all of whose members at work that day died.

Whirlwinds and pillars of fire at Motoyasu River

Hiroshima resident Koji Kitayama, 76, spoke of his final parting from his father, who was also a reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun, saying, “I worked as the coordinator of the coverage of the atomic bombing, but when it comes to talking about myself, I feel like I’m dipping into something very painful… I never talked about it when I was at the company.”

On August 5, 1945, Mr. Kitayama, who was a fourth-grader at Danbara National Elementary School, and his brother Takuji, a sixth-grader, were visited by their father at Shokoji Temple in Yamanouchi Higashi (now part of Shobara), Hiroshima Prefecture, to which the boys and others had evacuated. After Koji beat his father at shogi (Japanese chess) for the first time, Mr. Kitayama smiled and said, “You’ve gotten good.” Mr. Kitayama took the boys to the Shobara bureau of the Chugoku Shimbun and offered them a snack. Then the three of them headed for the station.

Koji urged his father to stay the night, but he declined, saying he had to be at work early the next morning. That was Koji’s last conversation with his father.

On August 6, as second in command, Kazuo Kitayama, then 40, led the mobilization of the members of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps for the demolition of buildings. At the Chugoku Shimbun Mr. Kitayama was assistant manager of the business department and manager of the sales department.

Men up to 65, women up to 45

In March 1945 the Cabinet approved a “Matter Regarding the Organization of Volunteer Citizens’ Corps.” On the grounds of the need to “fully prepare the homeland’s defenses,” all males from those who had completed the equivalent of sixth grade through those aged 65 as well as women through the age of 45 were mobilized. Employees of news organizations were not excepted.

The Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps was made up of “employees of the Chugoku Shimbun, of all newspaper and news service bureaus in Hiroshima, and of the Chugoku-Shikoku District Headquarters and Hiroshima Prefecture Bureau of the Japan Newspaper Public Corporation.”

Ichiro Osako, then 32, was a reporter who covered the Hiroshima Prefectural government and other assignments for the Chugoku Shimbun. He kept copies of the regulations of the volunteer citizens’ corps and a list of its members. Mr. Osako’s son, Akira, 59, a resident of Tokyo, has preserved them.

Below the name of Jitsuichi Yamamoto, 55, the president of the Chugoku Shimbun, who served as leader of the corps, are 364 names. They include the names of 23 employees of the Hiroshima bureau of the Domei News Agency (according to the March 1997 report of the Japan Press Research Institute) and the names of the chiefs of the Hiroshima bureaus of the Asahi and Mainichi newspapers. Insofar as can be estimated from the list of members, it is believed that around 330 of the members of the corps were employees of the Chugoku Shimbun.

According to the August 4 entry in “Hiroshima 1945” by Mr. Osako, the Chugoku Shimbun received consent from the Prefectural Volunteer Citizens’ Corps Headquarters (headed by the governor) for the group to be mobilized each day “to be made up of 40 employees of the paper and six from the Hiroshima bureaus of other papers.”

At that time, the downtown area of the Hiroshima delta was “taking precautions against attacks by enemy aircraft” (according to the August 4 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun), and the sixth phase of the demolition of buildings was in full swing.

In order to “establish several open spaces of about 30,000 tsubo (approximately 3.3 square meters) or 60,000 tsubo including water as evacuation areas” (July 23 edition), every day volunteer citizens’ corps and students were mobilized to tear down private homes and to clear away the debris. The plan was to clear a fire break of up to 198,000 square meters from Tsurumi-cho in the east to Koami-cho in the west.

On August 6, 541 people, including members of the Newspaper Volunteer Citizens’ Corps and first- and second-year students from the Hiroshima Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School), were in the area extending from Tenjin-machi Minamigumi, which fronts on the Motoyasu River, to Kobiki-cho. (Kobiki-cho is now part of Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward. It represents the entire area on the south side of the Peace Memorial Museum).

Just after they set to work the atomic bomb was dropped, and all of them died.

Eight-page account remains

There is an account of the devastation just after the bombing in notes made by Chishiki Mizuhara, a Chugoku Shimbun reporter who was then 34 years old.

“There was nothing but people crying out for help… I shook hands firmly with a friend within reach and said a final goodbye, telling myself to be strong, but we were both in tears.” Mr. Mizuhara somehow made it to the Motoyasu River.

“There were several groups of people, young and old. The river was at full tide. The flames engulfing the houses on both sides of the river repeatedly licked the entire surface of the water. Here and there on the surface of the river large whirlwinds and huge pillars of fire five or ten meters high would suddenly arise… One by one the groups of people along the riverbank were gradually swallowed up and disappeared as I watched.”

Mr. Mizuhara swam downstream to the Yorozuyo Bridge (about 890 meters from the hypocenter) and climbed up onto the riverbank. On August12 he arrived at the home of a friend in Itsukaichi (Saeki Ward). “I kept thinking: There must never again be another war,” he wrote. On August 16, the day after the war ended, Mr. Mizuhara died. He had been in charge of the coverage of the Second General Headquarters of the Imperial Army, which was established in Hiroshima in April.

Mr. Mizuhara’s account consists of eight pages of tightly written notes. Shigeki Omae (later mayor of Itsukaichi), who took care of Mr. Mizuhara at the end, submitted Mr. Mizuhara’s notes to a collection of accounts of the A-bombing compiled by the city in 1950. The accounts are now preserved in the city’s archives. Mr. Omae’s dedication read: “This account is dedicated to the memory of M, a reporter for C Co.”

On August 10, Kazuo Kitayama, the leader of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps, arrived at Kamisugi (now part of Miyoshi), to which his daughter, a second-year student at the municipal girls’ high school, had been evacuated. He was accompanied by a subordinate with whom he was friendly.

His daughter came to meet them pulling a large cart. Hiroshima resident Naoko Kurokawa, 80, said, “Dad was using a cane, but unlike Mom, who was covered in bandages so only her eyes could be seen, he could talk.” Ms. Kurokawa’s mother Futaba, then 33, was on her way to demolish buildings in Tsurumi-cho along the Kyobashi River when she was exposed to thermal rays from the atomic bombing. Her aunt brought her to Kamisugi.

45 mobilized on day of bombing

As for the number of members of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps who were mobilized on August 6, Ms. Kurokawa said, “I recall my father telling me there were 45. He also said only three of them got away and were able to be taken home. Dad spent the entire night in the river. He said he apologized the next day at work.”

Mr. Kitayama died on the morning of August 13. Koji and his brother were notified and hurried off. “We went to the crematorium on Mt. Kamisugi,” Koji said. “Seeing how badly my mother was burned…”

Futaba somehow survived. In 1947 she was hired by the Chugoku Shimbun and came to live in Hiroshima with her three children. Her account of her experiences is included in the collection of A-bomb accounts compiled by the city.

“A keloid about the size of my palm ran from my left cheek to my mouth and throat… But I keep working on account of my poor children.” Futaba died in 1980 at the age of 68.

Koji said emphatically, “My mother threw away half of her life as a woman because of the A-bomb. She made raising the three of us kids and putting us through college her reason for living, but I still resent the war.”

Tokuho Kobayashi, chief of the Hiroshima bureau of the Domei News Agency, was with the members of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps when they set out on August 6. He died on August 7 in Shinjo-cho (Nishi Ward), to which he had evacuated. Before he died he asked, “Did you file my initial report?” (This account was submitted to the August 1967 edition of the bulletin of the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association by Satoshi Nakamura, editor at the Hiroshima branch.)

Of the members of the citizens’ volunteer corps and the others who died, how many were employees of the Chugoku Shimbun?

According to “Eighty Years’ History of the Chugoku Shimbun” published in 1972, a total of 107 employees died. “People and History: Record of the Deceased from the Chugoku Shimbun,” which was published to mark the paper’s centennial, lists the names of 113 people. Hidetaro Hayashi, then 28, was on leave from his job in the paper’s transport department at the time of the bombing and was at home in Sarugaku-cho (now Ote-machi, Naka Ward). If his death from the A-bombing (July 23, 1997 edition) is included, it brings the total to 114. This means one third of the newspaper’s employees at the time died as a result of the atomic bombing.

Of course, not only employees of the Chugoku Shimbun were victims. Hiroshima Prefecture has preserved a “List of the Civilian Volunteers Corps Dead” broken down by job and by area. Based on this list and a survey by the city’s Peace Memorial Museum, the victims included 166 employees of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, which stretched across Koami-cho; 115 employees of Hiroshima Aircraft; 102 employees of Yutani Heavy Industries, which stretched across Tenjin-machi; and 107 employees of the prefecture. If Kawauchi (now part of Asa Minami Ward) and other nearby towns are included, at least 4,632 civilian volunteer corps members were killed.

At least 7,196 students from 51 schools died. With the cooperation of their families, the Chugoku Shimbun followed up on the deaths of 277 first-year students from the girls’ high school and learned that the remains of nearly 75 percent of them were never found (June 22, 2000 edition).

Those who were mobilized by order of the central government to create fire breaks or to work in production at munitions factories became victims of the atomic bomb, bringing heartbreak and suffering to the families they left behind.

(Originally published on March 31, 2012)

Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 3)