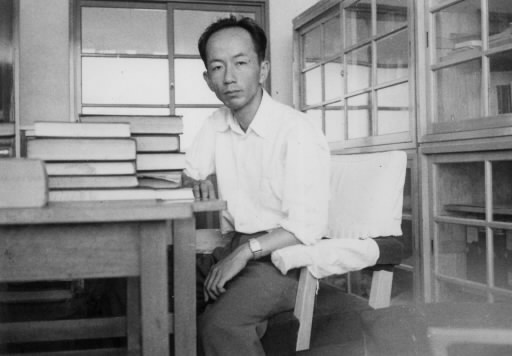

My Life: Interview with Makoto Kitanishi, political scientist, Part 7

Jul. 4, 2013

Instructor at Hiroshima University

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Running “Society of Academics”

In March 1954, the U.S. military tested a hydrogen bomb on Bikini Atoll. In November of that year, Mr. Kitanishi became a research assistant in the Faculty of Politics and Economics at Hiroshima University.

We used classrooms at the prefectural commercial high school in Eba (Funairi Minami, Naka Ward). (The faculty relocated to Higashi Senda-machi in 1957.) Tsugimaro Imanaka, who got me the post as a research assistant, also helped me find a place to live. It was right across the street from his place in Yoshijima (Yoshijima Higashi, Naka Ward). In fact, he was my landlord.

He often invited my wife and me over for dinner, and we sometimes played shogi. I was better than he was, and he was a sore loser. I think I was the only person he felt so at ease with, even among his students. So when he asked me to help him with the “Society of Academics” I accepted without any argument even though I thought the name sounded snobbish.

The official name was the “Society of Academics for the Preservation of Peace and Learning.” The Subversive Activities Prevention Act had become law in 1952, and people were worried about the possibility of the revival of the Public Order Preservation Act. That’s why the group was formed. When I joined, Mr. Imanaka was the president and Kiyoshi Sakuma (professor in the Faculty of Science) was secretary-general. There were about 150 members. Most of them were from Hiroshima University, but there were some from the women’s university (now the Prefectural University of Hiroshima) and Hiroshima Jogakuin University too.

The Society of Academics was formed in 1953. The following year the group published a collection of essays entitled “The Atomic Bomb and Hiroshima.” It included works by Ichiro Moritaki, Seiichi Nakano, Tomin Harada, and Naomi Shono, who were leaders of the peace movement in Hiroshima.

The society’s business affairs were handled by me, Suguru Yokoyama of the Faculty of Literature and Hiroshi Yamada of the Faculty of General Education. I could write in block style, which is easy to read, so I was in charge of mimeographing the society’s newsletter. I called myself the “mimeo killer.” The Hiroshima local of the teachers’ union provided funds to support our activities. The old education center was near Hiroshima University in Higashi Senda-machi (Naka Ward). Society members served as lecturers for the teachers’ union’s National Conference on Educational Research and other seminars for very low fees and got regular donations.

What surprised me when I came to Hiroshima was that scholars were treated very well. For example, the teachers at Hiroshima University could run a tab even if they were new customers. In Hakata merchants are traditionally strong, and people complained that Kyushu University (Hakozaki campus) blocked the eastern edge of town and prevented development. But when the Society of Academics held a press conference to issue a statement, it got a lot of coverage in the newspapers. The atmosphere at Hiroshima University was conservative, but as an educational group the society exerted quite a bit of influence.

After the Bikini incident, more and more people around the country began to call for the hydrogen bomb to be banned, and, in 1955, the first World Conference against Atomic & Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima. I decided to actively assist with that event.

(Originally published on April 17, 2013)

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Running “Society of Academics”

In March 1954, the U.S. military tested a hydrogen bomb on Bikini Atoll. In November of that year, Mr. Kitanishi became a research assistant in the Faculty of Politics and Economics at Hiroshima University.

We used classrooms at the prefectural commercial high school in Eba (Funairi Minami, Naka Ward). (The faculty relocated to Higashi Senda-machi in 1957.) Tsugimaro Imanaka, who got me the post as a research assistant, also helped me find a place to live. It was right across the street from his place in Yoshijima (Yoshijima Higashi, Naka Ward). In fact, he was my landlord.

He often invited my wife and me over for dinner, and we sometimes played shogi. I was better than he was, and he was a sore loser. I think I was the only person he felt so at ease with, even among his students. So when he asked me to help him with the “Society of Academics” I accepted without any argument even though I thought the name sounded snobbish.

The official name was the “Society of Academics for the Preservation of Peace and Learning.” The Subversive Activities Prevention Act had become law in 1952, and people were worried about the possibility of the revival of the Public Order Preservation Act. That’s why the group was formed. When I joined, Mr. Imanaka was the president and Kiyoshi Sakuma (professor in the Faculty of Science) was secretary-general. There were about 150 members. Most of them were from Hiroshima University, but there were some from the women’s university (now the Prefectural University of Hiroshima) and Hiroshima Jogakuin University too.

The Society of Academics was formed in 1953. The following year the group published a collection of essays entitled “The Atomic Bomb and Hiroshima.” It included works by Ichiro Moritaki, Seiichi Nakano, Tomin Harada, and Naomi Shono, who were leaders of the peace movement in Hiroshima.

The society’s business affairs were handled by me, Suguru Yokoyama of the Faculty of Literature and Hiroshi Yamada of the Faculty of General Education. I could write in block style, which is easy to read, so I was in charge of mimeographing the society’s newsletter. I called myself the “mimeo killer.” The Hiroshima local of the teachers’ union provided funds to support our activities. The old education center was near Hiroshima University in Higashi Senda-machi (Naka Ward). Society members served as lecturers for the teachers’ union’s National Conference on Educational Research and other seminars for very low fees and got regular donations.

What surprised me when I came to Hiroshima was that scholars were treated very well. For example, the teachers at Hiroshima University could run a tab even if they were new customers. In Hakata merchants are traditionally strong, and people complained that Kyushu University (Hakozaki campus) blocked the eastern edge of town and prevented development. But when the Society of Academics held a press conference to issue a statement, it got a lot of coverage in the newspapers. The atmosphere at Hiroshima University was conservative, but as an educational group the society exerted quite a bit of influence.

After the Bikini incident, more and more people around the country began to call for the hydrogen bomb to be banned, and, in 1955, the first World Conference against Atomic & Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima. I decided to actively assist with that event.

(Originally published on April 17, 2013)