Miyoko Sasaki, 84, Minami Ward, Hiroshima City

Oct. 2, 2013

Felt exhausted, in despair, but “I have to go on”

Miyoko Sasaki, (nee Adachi), lost the father she loved dearly, Itsuji, to the atomic bombing. Over the years she has felt sorrow and anguish, and even now, her memories bring her to tears. “I won’t take an airplane that was made by the company that built the B-29 bomber [Boeing, an American aerospace company],” she said. “Because one of those planes carried the atomic bomb.”

In August 1945, her father was working as an accountant at the army’s Chubu Headquarters in Osaka. On August 5, one day before the atomic bombing, he returned to Hiroshima. The next day, when the bomb was dropped, he was on his way to City Hall to take care of paperwork to relocate his family, who were living in Senda-machi, part of present-day Naka Ward, to an evacuation site in Koyo-cho, north of the city center in today’s Asakita Ward.

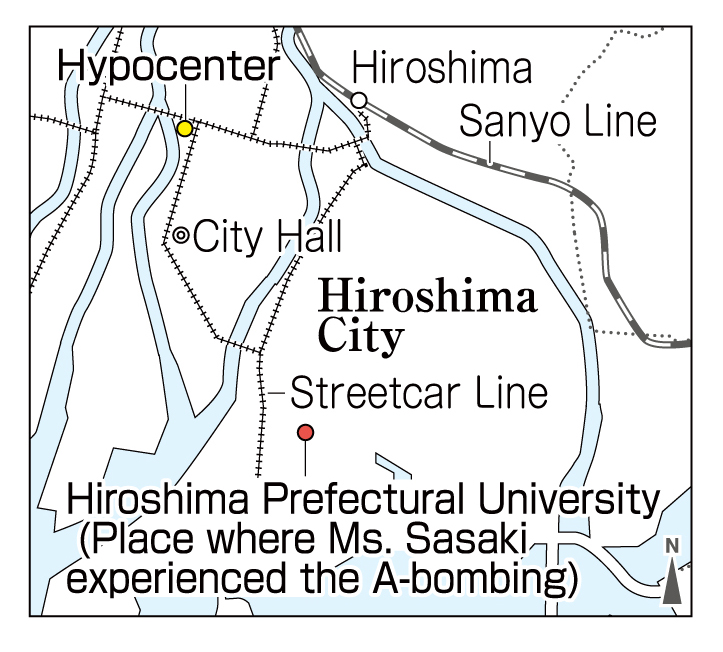

Ms. Sasaki was 16 years old and in her first year at the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women (now, Hiroshima Prefectural University), located in Ujina, in today’s Minami Ward, about 3.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. She was in the school auditorium, about to leave after listening to the principal speak, when there was a large flash and the chandelier hanging from the ceiling tumbled down. Fortunately, most of the students, including Ms. Sasaki, were unhurt.

Making use of a wooden door, she helped carry the wounded who had fled the city center. In the midst of these relief efforts, someone told her that her father had arrived at the school. Ms. Sasaki hurried to the main gate and found her father, badly burned all over his body. Without heeding the risks of his own condition, he had come to the school to check on his daughter’s safety.

She helped her father lie on a tatami floor at the school, but his burns were so severe that she was unable to cool him down with a wet towel. She could only fan him with a notebook. Her father’s skin turned black and rough, like asphalt, and from around August 8, the wounds became infested with maggots. Ms. Sasaki picked them out with chopsticks she cut in half.

On August 7, she walked back to Kamifukawa, her family’s evacuation site, and told her brother Seijo, 7, and other family members about her father. Because her father was in dire condition, she then traveled to Oasacho, in northern Hiroshima Prefecture, to pick up her brother Yoshinari, 10, who had earlier been evacuated out of the city in a group of children.

Their father sometimes called out the names of family members and murmured, “I see beautiful sights,” but he died on August 14.

After her father’s death, Ms. Sasaki was left with her mother and three younger siblings. Their house in Senda-machi had burned down. She felt exhausted, in despair, but when she saw the scar on her mother’s neck, suffered in Senda-machi as a result of the bomb’s heat rays, she told herself, “I have to go on.” She said she burned with hatred for the United States, thinking “Damn you for what you did!”

In the spring of 1948, Ms. Sasaki graduated from the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women. That fall, she got married. Her father-in-law opened a high-class Japanese restaurant in 1950 and she spent her days, until the business closed in 2004, busily working as a hostess there. Throughout the time, she didn’t share her account of the atomic bombing with the people around her. Recently, however, she thinks, “My son [who’s now 64] should know about my experience.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women: Building escaped fire, served as relief station

The Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women (now, Hiroshima Prefectural University, located in Minami Ward) was established in 1928 to provide continuing education to women who had graduated from elementary school (six years) and high school (four or five years).

According to a record of the damage wrought by the atomic bombing, on August 6, the day the bomb was dropped, about 160 first-year students, along with about 20 second- and third-year students who hadn’t been mobilized for work because of poor health or other reasons, were at the college. In addition, around 60 soldiers from the Akatsuki Corps, a military unit, were present at the college, too, waiting to ship out.

The college was located approximately 3.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, and there were injuries on the campus, but no deaths. However, two students who were ill and staying in a dormitory in Higashisenda-cho (in today’s Naka Ward) were killed. And six students who were on their way to school went missing, and were later identified as victims.

The auditorium was badly damaged, and the school building suffered damage, too. The wooden building leaned to one side, its windows shattered, but it escaped the fires that consumed the city. As a result, the building became a temporary relief station.

After the bombing, the city center was a burnt plain, with universities and other schools of higher education razed to the ground. For the next two years or so, the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women played an important role in the cultural life of Hiroshima.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Have a goal and work toward it

After losing her father, Ms. Sasaki grieved and wondered how she could go on living. But at the same time, she thought, “I have to help my mother.” Even though going on with her life was very hard, she had to find a new purpose in living.

We should try hard to set a goal for our life, and not give up easily in the things we do. (Miyu Okada, 12)

I want to cherish my family

It hit me hard how distressed and frustrated Ms. Sasaki must have felt when she couldn’t help her father, who she loved so much, when he was suffering there in front of her.

Ms. Sasaki told us, “Please cherish your parents.” I plan to change my attitude because I often talk back to my mother or my grandmother when I get upset at what they say. I want to appreciate the fact that they’re here in my life. (Marina Misaki, 14)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

During the war, Miyoko Sasaki (nee Adachi) and other girls enjoyed having their photographs taken at a portrait studio. From First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School in Nakamachi (part of present-day Naka Ward), she would run to a portrait studio near the Hondori shopping street with her classmates during recess to get their photos taken. The cost was reasonable and they used the money from their allowance. The picture of her at the age of 15 was taken at this studio. At the time, high school girls had particular hair styles in line with their grade: first- and second-year students had bobbed hair, third-year students parted their hair in front, and fourth-year students tied their hair up behind them.

Ms. Sasaki’s father, Itsuji, sent letters to her mother, Ryoko, every day from the places where he was working in Japan and overseas. Within the military, this fact became well known and eventually his letters could be delivered to their home addressed only to Ryoko Adachi, Empire of Japan.” When Miyoko and her 3-year-old sister Reiko saw the words “My beloved Ryoko” at the end of her father’s letters, they were surprised, because such direct expressions of love weren’t common in Japanese custom of the time. On the day of the atomic bombing, Reiko was mobilized to work in the village of Kawauchi, part of today’s Asaminami Ward, and she rushed to the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women to look after her wounded father with Miyoko. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on September 10, 2013)

Miyoko Sasaki, (nee Adachi), lost the father she loved dearly, Itsuji, to the atomic bombing. Over the years she has felt sorrow and anguish, and even now, her memories bring her to tears. “I won’t take an airplane that was made by the company that built the B-29 bomber [Boeing, an American aerospace company],” she said. “Because one of those planes carried the atomic bomb.”

In August 1945, her father was working as an accountant at the army’s Chubu Headquarters in Osaka. On August 5, one day before the atomic bombing, he returned to Hiroshima. The next day, when the bomb was dropped, he was on his way to City Hall to take care of paperwork to relocate his family, who were living in Senda-machi, part of present-day Naka Ward, to an evacuation site in Koyo-cho, north of the city center in today’s Asakita Ward.

Ms. Sasaki was 16 years old and in her first year at the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women (now, Hiroshima Prefectural University), located in Ujina, in today’s Minami Ward, about 3.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. She was in the school auditorium, about to leave after listening to the principal speak, when there was a large flash and the chandelier hanging from the ceiling tumbled down. Fortunately, most of the students, including Ms. Sasaki, were unhurt.

Making use of a wooden door, she helped carry the wounded who had fled the city center. In the midst of these relief efforts, someone told her that her father had arrived at the school. Ms. Sasaki hurried to the main gate and found her father, badly burned all over his body. Without heeding the risks of his own condition, he had come to the school to check on his daughter’s safety.

She helped her father lie on a tatami floor at the school, but his burns were so severe that she was unable to cool him down with a wet towel. She could only fan him with a notebook. Her father’s skin turned black and rough, like asphalt, and from around August 8, the wounds became infested with maggots. Ms. Sasaki picked them out with chopsticks she cut in half.

On August 7, she walked back to Kamifukawa, her family’s evacuation site, and told her brother Seijo, 7, and other family members about her father. Because her father was in dire condition, she then traveled to Oasacho, in northern Hiroshima Prefecture, to pick up her brother Yoshinari, 10, who had earlier been evacuated out of the city in a group of children.

Their father sometimes called out the names of family members and murmured, “I see beautiful sights,” but he died on August 14.

After her father’s death, Ms. Sasaki was left with her mother and three younger siblings. Their house in Senda-machi had burned down. She felt exhausted, in despair, but when she saw the scar on her mother’s neck, suffered in Senda-machi as a result of the bomb’s heat rays, she told herself, “I have to go on.” She said she burned with hatred for the United States, thinking “Damn you for what you did!”

In the spring of 1948, Ms. Sasaki graduated from the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women. That fall, she got married. Her father-in-law opened a high-class Japanese restaurant in 1950 and she spent her days, until the business closed in 2004, busily working as a hostess there. Throughout the time, she didn’t share her account of the atomic bombing with the people around her. Recently, however, she thinks, “My son [who’s now 64] should know about my experience.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women: Building escaped fire, served as relief station

The Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women (now, Hiroshima Prefectural University, located in Minami Ward) was established in 1928 to provide continuing education to women who had graduated from elementary school (six years) and high school (four or five years).

According to a record of the damage wrought by the atomic bombing, on August 6, the day the bomb was dropped, about 160 first-year students, along with about 20 second- and third-year students who hadn’t been mobilized for work because of poor health or other reasons, were at the college. In addition, around 60 soldiers from the Akatsuki Corps, a military unit, were present at the college, too, waiting to ship out.

The college was located approximately 3.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, and there were injuries on the campus, but no deaths. However, two students who were ill and staying in a dormitory in Higashisenda-cho (in today’s Naka Ward) were killed. And six students who were on their way to school went missing, and were later identified as victims.

The auditorium was badly damaged, and the school building suffered damage, too. The wooden building leaned to one side, its windows shattered, but it escaped the fires that consumed the city. As a result, the building became a temporary relief station.

After the bombing, the city center was a burnt plain, with universities and other schools of higher education razed to the ground. For the next two years or so, the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women played an important role in the cultural life of Hiroshima.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Have a goal and work toward it

After losing her father, Ms. Sasaki grieved and wondered how she could go on living. But at the same time, she thought, “I have to help my mother.” Even though going on with her life was very hard, she had to find a new purpose in living.

We should try hard to set a goal for our life, and not give up easily in the things we do. (Miyu Okada, 12)

I want to cherish my family

It hit me hard how distressed and frustrated Ms. Sasaki must have felt when she couldn’t help her father, who she loved so much, when he was suffering there in front of her.

Ms. Sasaki told us, “Please cherish your parents.” I plan to change my attitude because I often talk back to my mother or my grandmother when I get upset at what they say. I want to appreciate the fact that they’re here in my life. (Marina Misaki, 14)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

During the war, Miyoko Sasaki (nee Adachi) and other girls enjoyed having their photographs taken at a portrait studio. From First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School in Nakamachi (part of present-day Naka Ward), she would run to a portrait studio near the Hondori shopping street with her classmates during recess to get their photos taken. The cost was reasonable and they used the money from their allowance. The picture of her at the age of 15 was taken at this studio. At the time, high school girls had particular hair styles in line with their grade: first- and second-year students had bobbed hair, third-year students parted their hair in front, and fourth-year students tied their hair up behind them.

Ms. Sasaki’s father, Itsuji, sent letters to her mother, Ryoko, every day from the places where he was working in Japan and overseas. Within the military, this fact became well known and eventually his letters could be delivered to their home addressed only to Ryoko Adachi, Empire of Japan.” When Miyoko and her 3-year-old sister Reiko saw the words “My beloved Ryoko” at the end of her father’s letters, they were surprised, because such direct expressions of love weren’t common in Japanese custom of the time. On the day of the atomic bombing, Reiko was mobilized to work in the village of Kawauchi, part of today’s Asaminami Ward, and she rushed to the Hiroshima Prefectural College for Women to look after her wounded father with Miyoko. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on September 10, 2013)