Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Close-range Survivors 4

Aug. 25, 2014

Michie Kakimoto, 88: Tangerine-producing island

Inside streetcar in Sakan-cho at time of A-bombing

Charms still provide moral support

When the atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima, Michie Kakimoto, 88, was aboard a streetcar that had just crossed the Aioi Bridge, the T-shaped bridge that was the bomb’s target. Ms. Kakimoto now lives on Mikado Shima, a small island off the coast of Kure accessible by a 10-minute ferry ride from Osaki Shimojima. Thirty-eight people live on the island, which is covered with tangerines trees.

Ms. Kakimoto was interviewed while relaxing at her home by the sea. “I’m the only atomic bomb survivor on the island,” she said. “There’s no hospital and it’s inconvenient, but I don’t want to leave my hometown.” Until her legs and back gave out two years ago, she continued to grow tangerines, a business she took over from her parents. She lives alternately one week with her son Mitsugu, 64, who works at a boatyard on the island, and at a nursing home on Osaki Shimojima the next.

Her daughter Chiyoko Kakimoto, 62, a resident of Fukuyama, came back to Mikado Shima to sit in on her mother’s interview. “She hardly told us anything about the atomic bombing,” Chiyoko said. In response her mother pulled out a charm from Ishizuchi Shrine in Saijo, Ehime Prefecture that she wears around her neck. “I can’t help but think that this is what has kept me alive,” she said. She talked about the summer she was 19.

“A flash and a bang”

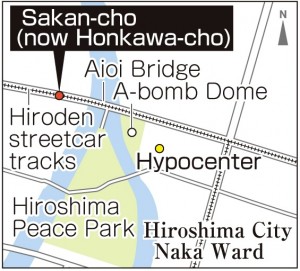

On the morning of August 6, Ms. Kakimoto boarded a streetcar in front of the Finance Ministry’s Monopoly Bureau (in what is now Minami-machi, Minami Ward). She had come to Hiroshima to visit a friend and had spent the night in the city. Just after the streetcar crossed the Aioi Bridge “suddenly there was a flash and a bang.” This is how Ms. Kakimoto described the moment the atomic bomb exploded when she was in Sakan-cho (now part of Honkawa-cho in Naka Ward), about 500 meters northwest of the hypocenter. She ducked down among the other passengers on the crowded train, and then, in her eagerness to escape, walked across the backs of those who had collapsed and climbed out a window.

According to the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, 63 streetcars were in service on the morning of August 6. The three streetcars – two wooden and one steel – that were traveling west of the Aioi Bridge toward Nishi Tokaichi were completely destroyed.

Many residents of the island were faithful adherents of Ishizuchi Shrine, and Ms. Kakimoto always wore a charm from the shrine. Clutching the charm, she wandered the city, which was filled with dead bodies, not knowing her way around. Near Hiroshima Station she came across a truck that was headed for Kure. From Kure she boarded a boat, determined to get home. She arrived on the island on August 8.

Once home she was afflicted with acute radiation sickness and suffered from a high fever, bleeding gums and hair loss.

“My parents fed me herbs and seafood that are good for you,” Ms. Kakimoto said. “I was luckier than those in the city who lost their homes and had nothing to eat.” She gradually recovered, and in 1949 she married. She and her husband had a son and two daughters. In 1956 they divorced, and Ms. Kakimoto supported her children by growing tangerines.

But over the years she continued to have fevers and get purple spots on her body. Because she had been caught in the black rain on the day of the A-bombing, whenever possible she refrained from going out in the rain. Even when working in the fields on sunny days she always took a covering for her head in case of a sudden shower. There was no doctor nearby who could examine her for the effects of radiation.

In 1962 she was diagnosed with hepatitis and was hospitalized at the Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital (now the Hiroshima Red Cross & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital) for one month. While she was able to undergo comprehensive treatment, she also saw the A-bomb survivor who shared her room die of liver cancer, and her fears could not be dispelled.

Swallowed frustration

Ms. Kakimoto was later certified as an atomic bomb survivor as a result of her hepatitis. “Some people in the neighborhood said, ‘Lucky you. You get money.’” Her children had gotten jobs off the island after graduating from junior high school, and she didn’t want them to worry about her medical expenses. She swallowed her vexation.

Her visits to Ishizuchi Shrine provided moral support. In 1946 she began visiting the shrine every year. Last year she went to the shrine with Chiyoko and got a new charm. “I didn’t know she was wearing one at the time of the A-bombing,” Chiyoko said. She occasionally expressed surprise as she listened to her mother’s account of her A-bombing experiences.

Every year as the anniversary of the A-bombing approaches there is an event at which survivors recount their experiences aboard a streetcar. “I couldn’t talk about it even if I were asked to,” Ms. Kakimoto said. “All I can do is pray for the health of my family.” When on the island, she pushes a small cart to Mikado Shrine, where she offers prayers to the patron deity. The good health of her five grandchildren is her fondest desire and what brings her happiness.

(Originally published on June 23, 2014)

と千代子さん親子-213x300.jpg)

西側で全壊全焼した木造路面電車の残骸-300x195.jpg)