Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Close-range Survivors 5

Aug. 25, 2014

84-year-old woman: On streetcar in Kawaya-cho

Woman agrees to interview on condition of anonymity

Still bothered by prospect of rumors

After repeated requests for an interview, an 84-year-old survivor of the atomic bombing agreed to talk about her experiences on condition that neither her name nor address be revealed. The woman lives alone in a small town in the mountains of Hiroshima Prefecture. She is one of the “close-range atomic bomb survivors” identified by Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Nuclear Medicine and Biology (now the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine) in 1972. Twelve of them, including the woman, are still living. Like Michie Kakimoto, 88, of Kure, who was featured in an article published on June 23, the woman was aboard a streetcar at the time of the A-bombing and miraculously survived.

At the time of the atomic bombing, the woman was a second-year student at the Hiroshima Electric Railway Girls’ School and was also working as a streetcar conductor. “I was busier with my work than I was with my studies,” the woman said. During the war, the railway company suffered a shortage of workers because many of its drivers and conductors were drafted, so it opened the school in 1943. There was also a dormitory in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward). The three-year school had 309 students.

Thermal rays blocked by other passengers

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the woman went to a stop near the dormitory to catch a streetcar to her worksite as a mobilized student. She squeezed onto the back of a crowded streetcar bound for Koi. The woman, who was then 15 years old and small for her age, was nearly crushed by the much taller male straphangers around her.

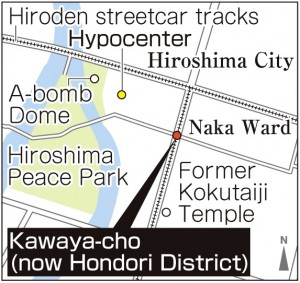

She recalls looking out of the streetcar and seeing a large tree receding into the distance near the Hiroshima branch of the Bank of Japan in Fukuro-machi (now part of Naka Ward). It was no doubt the large camphor tree on the grounds of Kokutaiji Temple (now located in Nishi Ward) just south of the bank. The woman’s atomic bomb survivor’s certificate states that she was in Ote-machi, 500 meters from the hypocenter, at the time of the A-bombing, but her actual location is believed to have been about 300 meters from the hypocenter near the Kawaya-cho streetcar stop (now part of Hondori).

When the atomic bomb exploded, “there was a loud bang, and everything went black,” the woman said. Before she knew it the entire area was in flames and her watch had stopped at 8:16. The train was so crowded she could hardly move, and the other passengers likely blocked the thermal rays and the shock wave. Showing a small white scar on the inside of her left elbow, the woman said, “I wasn’t burned, just cut here by glass or something.”

She ran into a nearby air raid shelter and waited there until the flames died down. The skin on both adults and children was peeling off and liquid was dribbling down. “It was truly a hell within a hell,” she said.

Three days later, on August 9, she made it to her family home in the mountains. Black spots appeared on her left thigh, and all her hair fell out. Neither her parents nor the local doctor knew how to treat her, so she simply rested. Amid the unprecedented chaos in Hiroshima, her school was closed.

After her hair grew back, the woman was employed as an office worker for the Hiroshima Electric Railway for about five years. In 1951, she married a man from her hometown who was employed by Japanese National Railways (now Japan Railways).

Her husband, who was a year younger, had been at Hiroshima Station at the time of the atomic bombing. The couple had no qualms about having children, and had a boy and a girl. But the woman’s husband, who had joined what is now the Ground Self-Defense Force, was concerned about the effect on his ability to be promoted, so he did not tell people that he was an A-bomb survivor nor did he get a survivor’s certificate.

Although the couple never told their neighbors in their hometown that they had been in Hiroshima at the time of the A-bombing, it was known to them. According to the woman, marriages to the couple’s children fell through on numerous occasions as the result of insensitive gossip by people who said that because both of their parents were A-bomb survivors they might have “strange” children. “I have two grandchildren, and they’re very bright,” the woman said proudly.

After four job transfers, primarily within western Japan, the couple returned to their hometown in 1984. The woman’s husband died of liver disease in 1997 at the age of 66.

Disturbed by debate

In addition to working in her garden every day, the woman spends a lot of time listening to the radio at home. She is disturbed by news about the right of collective defense and “bold” debate on the topic. “For people who haven’t experienced war or the A-bombing to talk that way…” she said angrily.

When asked again if she had any intention of revealing her name and talking about her A-bombing experiences, she remained adamant. “There are still people who say things,” she said. “People will inevitably talk.”

As I opened the door and stepped outside, something white and downy was floating in the air. “Chestnut blossoms,” the woman said. “The air here is really fresh – not like the air in town. I want to live as long as possible here. That’s the sole duty of survivors.” The stooped woman slowly got to her feet and saw me off.

(Originally published on June 30, 2014)

一帯の廃虚-300x283.jpg)