Special Series: 60 Years of RERF, Part III [2]

Sep. 8, 2014

Hiroshima and the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission: Survey of newborns

by Hiromi Morita, Staff Writer

This feature series on the past and future of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) originally began to appear in the Chugoku Shimbun in June 2007.

Submitting reports without knowing aims of the research

The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), which was established by the United States in Hiroshima in 1947, launched an extensive study on newborn babies the following year. The prompt start to this six-year research project points to the extraordinarily high level of interest held by the United States concerning the question of whether babies born to survivors of the atomic bombings suffered genetic damage--a question that has yet to be clearly answered to this today.

Haruko Okubo, 88, still remembers the chaotic days she weathered after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. “Many people were worried about giving birth to children with abnormalities,” she said. During her almost 70-year career as a midwife, Ms. Kubo, a resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima, has had a hand in more than 8,000 births.

“In those days, we were told to report immediately on any abnormalities found in expectant mothers or in the delivery of their babies,” Ms. Okubo recalled. “Midwives in the city of Hiroshima had to submit documents, and it looked like a lot of work, but in our area we weren’t asked to cooperate with ABCC’s research.”

The area where Ms. Okubo lived at the time was a village that lay outside the city limits, so she was part of a group of midwives that was separate from the midwives of Hiroshima. “I heard another midwife say that the Americans came to ask for information in Hiroshima with annoying frequency,” she said.

On the early morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Okubo saw off neighbors headed to central Hiroshima as voluntary workers. Her own duties as a midwife kept her in the village, and this saved her from the fate of these others. After the bombing, she dedicated time to caring for the survivors. Some had been burned so badly that their faces were deformed.

Ms. Okubo was left with strong feelings of guilt over having survived while so many died. But she devoted herself to delivering babies after the war, and sometimes her maternity clinic was filled to capacity. It was a joy for her to be surrounded by babies.

“I suppose those reports and documents helped the Americans understand the effects of the bomb,” she said. “This is what the midwives of Hiroshima believed as they attended to their duties.”

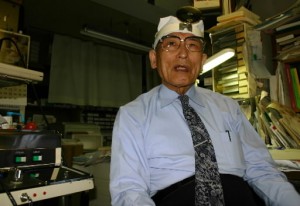

Takashi Takemoto, 82, a medical doctor, worked in the heredity division of the ABCC between 1950 and 1954. At the time of the bombing, he lived in the city of Okayama. The morning after the blast, he returned to Hiroshima to search for family members and was exposed to radiation from the bomb. Looking back on the time when he landed a job with the ABCC, an organization founded by the United States, he said, “I was struggling to survive in a land that was devastated and under occupation.”

His first assignment was to pursue research on newborns. He carried cards, typed with the addresses of households that had babies, and made door-to-door visits. He was not told whether or not the parents were A-bomb survivors in order to prevent bias from influencing the survey. He examined the presence or absence of congenital abnormalities, and gave mothers soap made in the United States.

Dr. Takemoto said, “It seems that they identified almost 100 percent of the newborn babies born to survivors.” Feeling that he was being taken advantage of by the American side, he quit working for the ABCC. “I just followed their instructions and wrote reports,” he said. He was not given any information about how the ABCC was managed and had no way of knowing how his reports were used in the United States.

(Originally published on June 7, 2007)