Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Paper Monuments 4

Feb. 18, 2015

Recollections and Stars Are Watching express sorrow for lost children

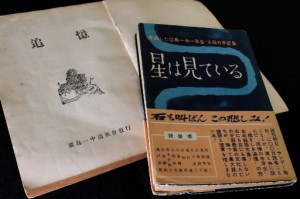

About 500 copies of the book were printed at Hiroshima Prison. The collection of A-bomb experiences, not intended for sale, drew media attention and awareness from the public. Published by the Association of Bereaved Families of Hiroshima First Middle School in April 1954, the book, then titled Tsuioku (Recollections), contained 86 written accounts.

The Sunday Mainichi and Shukan Asahi, two major weekly magazines, each with a circulation of one million at the time, featured excerpts of the book in their August 1 editions. Meanwhile, 33 of the accounts from Tsuioku were published by Masu Shobo, a publisher in Tokyo, on August 3 of that year under the title Hoshi wa Miteiru (Stars Are Watching). The following year, an NHK radio program called “My Bookshelf” narrated the accounts continuously for three days, starting on August 8.

353 students lost their lives

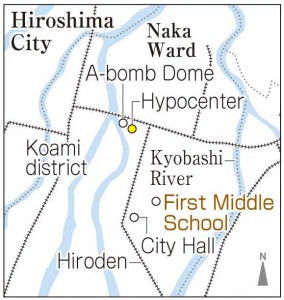

Hiroshima First Middle School (now Kokutaiji High School) lost 353 students in the atomic bombing. They perished in the school building, located about 800 meters away from the hypocenter, or at sites where they were mobilized to help dismantle buildings to make fire lanes near Hiroshima City Hall and in the Koami district (now in the area transformed into Peace Boulevard).

The book’s written accounts, filled with the mourning of parents whose beloved children were stolen away in the atomic bombing, was met by a powerful response. In March 1954, just a month before the book was first published, crew members of a Japanese fishing boat, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), were exposed to radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test conducted by the U.S. military. This event, dubbed the Bikini Incident, shocked the public and triggered nationwide signature drives to ban atomic and hydrogen weapons. It also stirred renewed interest in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“My father was thinking that he, as a military man, should have died instead of his son,” said Takatora Masaki, 79, a resident of Tokyo, showing letters exchanged between his father and mother in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. These, and a will his father penned, indicate that he had contemplated suicide after the war.

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Masaki’s older brother Yoshitora, who was 13 at the time, experienced the atomic bombing while in the school building. He managed to return, on his own power, to the town of Kuba (now part of Otake City), where his mother Tomoko, then 35, and Mr. Masaki himself had evacuated before the bombing. But on August 29, he passed away.

Their father, Ikutora, 42 at the time, was a captain in the technical department of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Early on, he learned that the new bomb dropped on Hiroshima, his hometown, was an atomic bomb, but was unable to return to the family and hold his eldest son’s ashes until September 21.

Recording the life of a lost son

In his written account for the book, Ikutora records the life of his lost son by quoting Yoshitora’s words: “I want to be able to swim well this year by practicing in the river [Kyobashi River] behind us.” Ikutora continues to recall what his son said and did in his last days of life: “I used cardboard to make the school emblem of First Middle School. When I get better, I look forward to going back to school and taking it with me.” Ikutora also blames himself for recommending that Yoshitora attend First Middle School.

The title of the book, Stars Are Watching, comes from the account written by the mother of Hirohisa Fujino, a first-year student who was 13 years old at the time. Hirohisa’s mother, Toshie, was 41.

She writes: “I have come to feel that all their souls have gone to the sky and become stardust. They are silently watching over us each night so that this tragedy is not repeated again on the earth.”

Masayuki Akita (who died in 1975 at the age of 79) was the leader of the group of bereaved families and had talked about the effort to collect these accounts. His words later appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on July 26, 1975: “Parents can never forget the loss of their children. These written accounts serve as graves for their children in the hearts of family members.”

Stars Are Watching was republished by the association three times, the last printing in 2005. Five years ago, the book was included in a series of books entitled Heiwa Bunko (Peace Pocket Books).

Mr. Masaki said, “There are now only a few parents who can tell others about their experience of losing their children in such a terrible way, so I sincerely hope that the collection will be read widely.” His father passed away in 1990, followed by his mother in 2006.

To comfort Yoshitora’s spirit, their father, Ikutora, carved and erected a stone statue of Kannon, the deity of mercy. On the statue was inscribed a haiku poem he had included in his written account for the collection. It reads: “A firefly in autumn, out of season, illuminates parents in anguish.” Mr. Masaki, who was present at the death of his elder brother, has attended the memorial ceremony held by First Middle School each year since his retirement in his early 70s, carrying the thoughts of his parents with him.

Realizing that the number of siblings of the lost students is declining, Mr. Masaki began organizing the letters and diaries left by his parents. It was then that he found his own essay, written in 1946, the year after the atomic bombing: “Memories of My Dear Elder Brother.”

Reading this essay, he was again struck by, as he had put it, “the cruelty of war and the sorrow of a family that was forced to sever ties with a loved one.”

(Originally published on February 10, 2015)