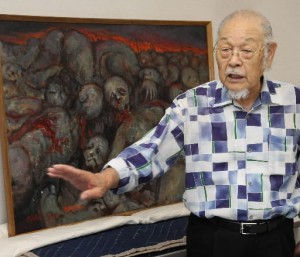

Ryo Usagawa, 84, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Sep. 25, 2015

Oil painting depicts devastation of atomic bombing

by Gosuke Nagahisa, Staff Writer

An oil painting titled “Reizan” (“Ghostly Mountain”) is held in a storage room at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in Naka Ward. It depicts piles of naked corpses in the flaming ruins of the atomic bombing. The painter, Ryo Usagawa, whose real name is Yoshitaka Usagawa, rendered the devastation he saw that day, 70 years ago, near Hakushima-cho (now part of Naka Ward). At the time of the bombing, Mr. Usagawa was 14 years old.

He made the painting in 1961, 16 years after the A-bomb attack, then donated it to the museum. In late August, after an interval of about half a century, he saw the painting again. “I can still recall the rumbling sound and the smell,” he said. “I never want to see a scene like that again.”

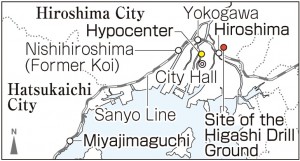

In the spring of 1945 he joined the former Japan National Railway and did repair work on the railway tracks. On the morning of August 6, he was fishing for octopus, to have more to eat at lunch, with his coworkers on a pier in Miyajimaguchi (now part of Hatsukaichi City). They were about 15 kilometers from the A-bomb’s hypocenter. Suddenly, there was a blinding flash of light. Mr. Usagawa heard a loud boom and a rumbling in the ground, then saw a mushroom cloud rising above the city of Hiroshima.

His supervisor directed him and his coworkers to go to the Higashi Drill Ground (located in today’s Higashi Ward) on the north side of Hiroshima Station (now in Minami Ward) for rescue operations. Including Mr. Usagawa, there were about 15 people in this group. They took a diesel railcar from Miyajimaguchi to Koi Station (now Nishihiroshima Station in Nishi Ward), then walked along the train tracks.

The station building at Yokogawa Station (now in Nishi Ward) had collapsed, and fire was approaching in the vicinity. He heard a woman’s voice calling for help from under the fallen building. Mr. Usagawa took a crowbar and tried to lift a pillar, but it wouldn’t budge. With the flames closing in, he had to flee. He says he still remembers, even today, the sound of her voice.

While heading toward Hiroshima Station without uttering a word, he heard the groans of the victims pleading for water from all around, as if they were welling up from the very earth. He saw a baby pawing at the breasts of a mother who lay motionless. “It was hell. And I was angry.” His painting reflected the sights he witnessed at that time.

He and his coworkers arrived at the Higashi Drill Ground before noon. Mr. Usagawa was assigned the task of cremating unidentified bodies, which were carried in one after another. The skin of the victims was peeling away and even their gender could not be identified. He piled up the bodies on railroad ties, doused the pile with heavy oil, and set them ablaze. He said, “Who would do this sort of thing? Why did they have to meet such tragic deaths?”

On the night of August 9, after three full days of this work, he walked back to his home in Miyauchi Village (now part of Hatsukaichi City) and told his parents that he was quitting his job. He could no longer endure the horrific assignment of cremating the dead.

After frequently changing jobs, including working as a taxi driver, a printer, and a carpenter, he began a career as an oil painter in his late 20s. Today he serves as an honorable commissioner of Daichowakai, a national association of representational painters.

In all his works, “Reizan” is the only painting which depicts the devastation of the atomic bombing. While he said he felt a responsibility to hand down his memories, as a painter, to the next generations, “All I could do was paint that one painting.” It was too painful for him to recall his experience of the atomic bombing beyond that.

His harrowing memories influenced the style of his paintings. Nothing was more frightening than human beings, he felt, who would wage war in such ways. “I was moved to paint people from behind,” he said, “showing their backs, the furtive parts of their bodies.” He went on to produce many paintings, one of which shows an old man from behind, walking along with his shoulders slumped.

His former coworkers of the Japan National Railway have died, one after the other, over the past several years, and he began to feel more strongly about speaking out. He now shares his experience of the atomic bombing at junior high schools. “If everyone would live in harmony with their neighbors, war could be prevented,” he said, in a message for young people.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Conveying his A-bomb experience

Mr. Usagawa was reluctant to talk about his A-bomb experience or depict it in his paintings. But as he grew older, he began to think that he should tell others about his account. Though his memories are painful, he felt that he had to face them and convey them to the next generations. With this in mind, I want to help share his experience with many people. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 13)

Deepen mutual understanding with others

Mr. Usagawa said, “Human beings waged war and dropped the atomic bomb. I want everyone to value life.” To today’s youth, he made the strong message: “Feel the warmth of your neighbors by joining hands to create a peaceful community.” I think I have to help fulfill his hopes. I want to talk with people who are different and have the courage to deepen our mutual understanding. (Yoshiko Hirata, 14)

Shocked that a 14-year-old boy cremated bodies

I was shocked to hear that Mr. Usagawa cremated so many bodies when he was 14 years old, younger than I am now. He told us about the sounds and smells at that time, which only people who experienced the bombing could describe, and are things we don’t usually imagine. He said over and over that he never wants to see such awful sights again. I want to help keep the world peaceful so these terrible scenes will not be repeated. (Kyoka Yamada, 17)

(Originally published on September 7, 2015)