Hiroshi Masaoka, 90, Higashi Ward, Hiroshima

Nov. 25, 2015

by Masahiro Yanagimoto, Staff Writer

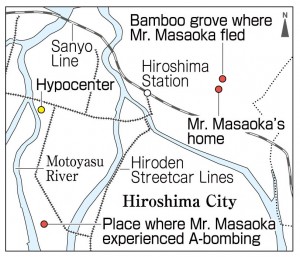

Hiroshi Masaoka, who experienced the atomic bombing in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward), about 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, suffered terrible burns to the left side of his upper body and his right arm, and hovered between life and death. But he was blessed with fortunate care and recovered. After the war, he joined Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation) and ultimately became a senior managing director. Mr. Masaoka says, “Nothing is more terrible than the destruction caused by an atomic bombing. But we go on living, and we make the present better and do things that can make others happy.” His experience of the atomic bombing, which caused widespread suffering and loss of innocent life, spurred his efforts to help reconstruct the city.

Back then Mr. Masaoka was 20 years old and a second-year student at the Hiroshima Technical Institute (now the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). On August 6, 1945, he was in his teacher’s office with three classmates. When someone said that something was falling from the sky, he approached the window. At that instant there was a blinding flash and his body was hit by burning heat, like a swarm of fireflies. When he dove under a table, he found that the floor was being pushed upward by the powerful winds from the blast and the building was pitching to one side.

Mr. Masaoka fled the room with the classmates who were with him and sought refuge in the nearby Motoyasu River, as the tide was rising. The homes in the area had collapsed, and all he could hear was his classmates’ voices. Beyond that, their surroundings were silent.

He returned to the institute then rode to Ujina (now part of Minami Ward) on a military truck. At first, Mr. Masaoka thought that a bomb had been dropped near his school, but he couldn’t comprehend what had happened when he witnessed the dreadful sights of the devastated city.

His sister, Ritsuko, then 18, was working for the Akatsuki Corps in Ujina. When he found her, hoping to see her before he died, she cooled his burns with ice.

After resting until around 3 p.m., he walked along the Ujina Line streetcar tracks which connected Ujina Port and Hiroshima Station, heading toward the Onaga district (now part of Higashi Ward), where his home was located. “If I’m going to die, I want to die at home,” he thought while stopping every few minutes to rest. When he finally arrived at a bamboo grove in the neighborhood, where his family had planned to flee in the event of an emergency, it had already grown dark. With relief, he reunited with his father and mother, and then he collapsed.

After that, Mr. Masaoka was unconscious until August 15. His mother, Asako, then 41, was given guidance from a burn specialist who had also fled to the bamboo grove. Following his advice, she melted antiperspirant powder with vegetable oil, spread it on old sheets of calligraphy paper, applied this mixture to the burns, then covered them with wet towels. She also helped him drink liquid extracted from the leaves of persimmon trees by the bamboo grove and a type of penicillin that her sister obtained from her workplace.

Fate was kind, and he was able to recover as he cooled his burns in the river and with ice. In late August he was on his feet again and he did not develop keloid scars as a result of his burns.

Mr. Masaoka joined Toyo Kogyo in 1947 and began his career as a factory worker because he wanted to learn about the manufacturing process. “I wanted to continue my education, but I was too occupied with the atomic bombing and Japan’s defeat in the war to study,” he recalled. “And I wanted to help earn money for our family.”

In the beginning, his work involved cleaning the factory, but he was given more opportunity after several years passed and put in charge of producing cylinders for engine parts. Leaving factory work around 1960, he became involved in rebuilding the retail side of the business in the United States, finally retiring from the post of senior managing director in 1988. “In this way,” he said, “I was involved in Hiroshima’s recovery.”

Mr. Masaoka heard that the supplies in the military-related facilities were quickly pilfered after the war ended. Ropes were stretched around burnt ruins before the landowners knew it, and some people’s land was nearly seized. It was a state of anarchy, the consequence of war. This is why Mr. Masaoka feels peace is so fundamental and he hopes that young people will find ways to solve problems through dialogue, not fighting.

Want to continue interviewing A-bomb survivors

What surprised me most was that no bodies came floating down the river when Mr. Masaoka jumped into the water. Because all the stories that I’ve heard mention that scores of bodies were floating on the river. I learned that it’s important to immediately cool the skin if you get burned. I recognized, too, that war must never be waged again. I want to continue interviewing A-bomb survivors. (Felix Walsh, 13)

War changed people’s nature

Mr. Masaoka said that the city was in a state of anarchy after the war, and even if people did wrong or committed crimes, no one could stop them. He also told us how all the rice in a rice warehouse was stolen by rioters in one night. War changed people’s nature. No matter how tough a situation might be, it’s important that our basic nature remain the same. I don’t want to change, even in difficult circumstances. (Hisashi Iwata, 14)

Realizing the importance of mutual understanding

Mr. Masaoka said again and again, “We should talk face to face.” If each side won’t give an inch, thinking they’re right, there will be conflict. I think we can avoid conflict if we seek mutual understanding and gradually find a place of compromise after talking it out, even if the discussion is uncomfortable. If we continue doing these things, I think we can avoid war. (Hiromi Ueoka, 14)

(Originally published on November 10, 2015)

Dreadful experience served as driving force in reconstructing Hiroshima

Hiroshi Masaoka, who experienced the atomic bombing in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward), about 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, suffered terrible burns to the left side of his upper body and his right arm, and hovered between life and death. But he was blessed with fortunate care and recovered. After the war, he joined Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation) and ultimately became a senior managing director. Mr. Masaoka says, “Nothing is more terrible than the destruction caused by an atomic bombing. But we go on living, and we make the present better and do things that can make others happy.” His experience of the atomic bombing, which caused widespread suffering and loss of innocent life, spurred his efforts to help reconstruct the city.

Back then Mr. Masaoka was 20 years old and a second-year student at the Hiroshima Technical Institute (now the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). On August 6, 1945, he was in his teacher’s office with three classmates. When someone said that something was falling from the sky, he approached the window. At that instant there was a blinding flash and his body was hit by burning heat, like a swarm of fireflies. When he dove under a table, he found that the floor was being pushed upward by the powerful winds from the blast and the building was pitching to one side.

Mr. Masaoka fled the room with the classmates who were with him and sought refuge in the nearby Motoyasu River, as the tide was rising. The homes in the area had collapsed, and all he could hear was his classmates’ voices. Beyond that, their surroundings were silent.

He returned to the institute then rode to Ujina (now part of Minami Ward) on a military truck. At first, Mr. Masaoka thought that a bomb had been dropped near his school, but he couldn’t comprehend what had happened when he witnessed the dreadful sights of the devastated city.

His sister, Ritsuko, then 18, was working for the Akatsuki Corps in Ujina. When he found her, hoping to see her before he died, she cooled his burns with ice.

After resting until around 3 p.m., he walked along the Ujina Line streetcar tracks which connected Ujina Port and Hiroshima Station, heading toward the Onaga district (now part of Higashi Ward), where his home was located. “If I’m going to die, I want to die at home,” he thought while stopping every few minutes to rest. When he finally arrived at a bamboo grove in the neighborhood, where his family had planned to flee in the event of an emergency, it had already grown dark. With relief, he reunited with his father and mother, and then he collapsed.

After that, Mr. Masaoka was unconscious until August 15. His mother, Asako, then 41, was given guidance from a burn specialist who had also fled to the bamboo grove. Following his advice, she melted antiperspirant powder with vegetable oil, spread it on old sheets of calligraphy paper, applied this mixture to the burns, then covered them with wet towels. She also helped him drink liquid extracted from the leaves of persimmon trees by the bamboo grove and a type of penicillin that her sister obtained from her workplace.

Fate was kind, and he was able to recover as he cooled his burns in the river and with ice. In late August he was on his feet again and he did not develop keloid scars as a result of his burns.

Mr. Masaoka joined Toyo Kogyo in 1947 and began his career as a factory worker because he wanted to learn about the manufacturing process. “I wanted to continue my education, but I was too occupied with the atomic bombing and Japan’s defeat in the war to study,” he recalled. “And I wanted to help earn money for our family.”

In the beginning, his work involved cleaning the factory, but he was given more opportunity after several years passed and put in charge of producing cylinders for engine parts. Leaving factory work around 1960, he became involved in rebuilding the retail side of the business in the United States, finally retiring from the post of senior managing director in 1988. “In this way,” he said, “I was involved in Hiroshima’s recovery.”

Mr. Masaoka heard that the supplies in the military-related facilities were quickly pilfered after the war ended. Ropes were stretched around burnt ruins before the landowners knew it, and some people’s land was nearly seized. It was a state of anarchy, the consequence of war. This is why Mr. Masaoka feels peace is so fundamental and he hopes that young people will find ways to solve problems through dialogue, not fighting.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Want to continue interviewing A-bomb survivors

What surprised me most was that no bodies came floating down the river when Mr. Masaoka jumped into the water. Because all the stories that I’ve heard mention that scores of bodies were floating on the river. I learned that it’s important to immediately cool the skin if you get burned. I recognized, too, that war must never be waged again. I want to continue interviewing A-bomb survivors. (Felix Walsh, 13)

War changed people’s nature

Mr. Masaoka said that the city was in a state of anarchy after the war, and even if people did wrong or committed crimes, no one could stop them. He also told us how all the rice in a rice warehouse was stolen by rioters in one night. War changed people’s nature. No matter how tough a situation might be, it’s important that our basic nature remain the same. I don’t want to change, even in difficult circumstances. (Hisashi Iwata, 14)

Realizing the importance of mutual understanding

Mr. Masaoka said again and again, “We should talk face to face.” If each side won’t give an inch, thinking they’re right, there will be conflict. I think we can avoid conflict if we seek mutual understanding and gradually find a place of compromise after talking it out, even if the discussion is uncomfortable. If we continue doing these things, I think we can avoid war. (Hiromi Ueoka, 14)

(Originally published on November 10, 2015)