Survivors’ Stories: Kenzo Masui, 91, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

Apr. 2, 2018

World of death, like a silent movie

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Kenzo Masui (Chen Jigyo), 91, was born in Taiwan at the time it was under Japanese rule.

His hometown was Lukang, on the west coast, and he was the third son of six children. His family was poor, and when he was 16, he entered a sailors’ training school established by the Governor-General of Formosa. Having adopted a Japanese name, he identified himself as Kenzo Tagawa and became a sailor of the Kaisoku Maru, an oil tanker owned by a Japanese shipping company, after he graduated from school in 1944.

In July 1945, the ship at its moorings at Kure Port became a target in a bombardment by U.S. planes and was sheared in two, then sank. Mr. Masui survived the attack, but he had nowhere to go in Japan. He then began to serve as a sailor, living in a dormitory near the naval port of Ujina.

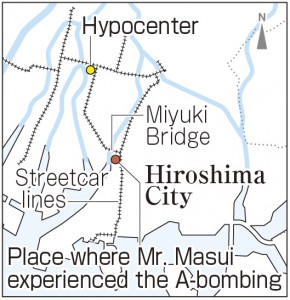

On the morning of August 6, he headed to an ice manufacturer in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward), pushing a two-wheeled cart with a colleague from Taiwan as he was asked to. Along the way, he saw the brilliant flash of the atomic bomb.

He heard a great roaring sound and saw smoke rise from the city center. Back then, he was 18 years old. Not knowing what was happening, both of them went to the hypocenter because they were curious to see a fire in the downtown area.

When they crossed Miyuki Bridge, located 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, they saw that houses had collapsed as far as the eye could see. A thick cloud spread out over their heads and things became dim. It was around 8:30 in the morning. Mr. Masui said, “I got the feeling that we had strayed into a world of death, like a silent movie.”

Mr. Masui heard the crackling sound of burning trees and low voices, here and there, begging for water from the wreckage of buildings. They went on further, to near the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, but turned back because they felt the way forward was ominous.

Mr. Masui remembers going back to Ujina Port with his friend and feeling dazed, leaning against a tree in front of the post office. People with disheveled hair and burnt skin and two-wheeled carts piled with bodies came to the port, one after another, on the street before them. Looking back now, they may have been headed to Ninoshima Island, where a temporary relief station was established.

When Mr. Masui returned to the dormitory and took a bath, his hair came out in a handful, and he had diarrhea for a week from the day after the A-bomb attack. These symptoms were likely aftereffects from his exposure to the bomb’s radiation.

After the war, he did not have enough money to return to his homeland. Mainland China, where the Chinese Communist Party now ruled, and the island of Taiwan, governed by the Republic of China and ruled by the Kuomintang, had fallen into disorder so he stayed in Japan. He pursued different types of work and moved from place to place in the Chugoku region and Kyushu. This was back when there was strong discrimination against people from other countries and A-bomb survivors. Thus, he told others that he spoke a dialect of Japanese because he was from Kyushu.

The turning point in his life arrived in 1960. Mr. Masui married Kiyoko, now 78, who was working alongside him at a beer hall in Hiroshima. The following year, their daughter was born, Mika Kusaka, now 56. He opened a Chinese restaurant downtown, seeking to add further stability to his life, and obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate around this time.

His fried rice and dumplings became popular because he added small twists to them, and his restaurant became a flourishing business. In 1969, he moved his restaurant to a site across the river from the Peace Memorial Park and named it Heiwa-rō with the Chinese character meaning “peace.” After retiring from this restaurant, where he had worked for about 20 years, he acquired Japanese nationality. He joined an around-the-world trip organized by Peace Boat, a non-governmental organization (NGO), and saw scars left by the war in about 40 countries, including Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines.

Takashi Kusaka, 25, Mr. Masui’s first grandchild, whose first name is derived from Mr. Masui’s Taiwanese name, plans to travel abroad on Peace Boat in September and share his grandfather’s A-bomb experience. “To understand other people is the first step for creating a peaceful world,” Mr. Masui said, conveying his hopes. “I’d like my grandson to exchange views and ideas with others, wherever he goes, in place of me.”

Teenagers’ impressions

I would be in tears

It was the first time I listened to the experience of an A-bomb survivor from Taiwan. Mr. Masui was at the mercy of history, and he suffered many hardships, but he still looked happy. If I were in his shoes, I would be in tears, wondering, “Why did I have to experience such a terrible thing? I want to go back to my own country.” I knew about A-bomb survivors from other countries, but I want to view Japanese history with the history of other countries in mind, such as why those people came to Japan. (Hitoha Katsura, 13)

Surprised by Japanese-style education in Taiwan

Mr. Masui said, “It’s important to exchange views with consideration for other people.” I think he said this because he experienced life from the perspective of someone who’s both Taiwanese and Japanese. He also told us about the relationship between Taiwan and Japan from the days before the war to the present. In particular, I was surprised to hear that the Japanese-style education was carried out in Taiwan, especially when it was a Japanese colony. I thought how it’s important to know other people’s viewpoints and widen my perspective in order to help foster mutual understanding. (Anna Ikeda, 16)

(Originally published on April 2, 2018)

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Kenzo Masui (Chen Jigyo), 91, was born in Taiwan at the time it was under Japanese rule.

His hometown was Lukang, on the west coast, and he was the third son of six children. His family was poor, and when he was 16, he entered a sailors’ training school established by the Governor-General of Formosa. Having adopted a Japanese name, he identified himself as Kenzo Tagawa and became a sailor of the Kaisoku Maru, an oil tanker owned by a Japanese shipping company, after he graduated from school in 1944.

In July 1945, the ship at its moorings at Kure Port became a target in a bombardment by U.S. planes and was sheared in two, then sank. Mr. Masui survived the attack, but he had nowhere to go in Japan. He then began to serve as a sailor, living in a dormitory near the naval port of Ujina.

On the morning of August 6, he headed to an ice manufacturer in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward), pushing a two-wheeled cart with a colleague from Taiwan as he was asked to. Along the way, he saw the brilliant flash of the atomic bomb.

He heard a great roaring sound and saw smoke rise from the city center. Back then, he was 18 years old. Not knowing what was happening, both of them went to the hypocenter because they were curious to see a fire in the downtown area.

When they crossed Miyuki Bridge, located 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, they saw that houses had collapsed as far as the eye could see. A thick cloud spread out over their heads and things became dim. It was around 8:30 in the morning. Mr. Masui said, “I got the feeling that we had strayed into a world of death, like a silent movie.”

Mr. Masui heard the crackling sound of burning trees and low voices, here and there, begging for water from the wreckage of buildings. They went on further, to near the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, but turned back because they felt the way forward was ominous.

Mr. Masui remembers going back to Ujina Port with his friend and feeling dazed, leaning against a tree in front of the post office. People with disheveled hair and burnt skin and two-wheeled carts piled with bodies came to the port, one after another, on the street before them. Looking back now, they may have been headed to Ninoshima Island, where a temporary relief station was established.

When Mr. Masui returned to the dormitory and took a bath, his hair came out in a handful, and he had diarrhea for a week from the day after the A-bomb attack. These symptoms were likely aftereffects from his exposure to the bomb’s radiation.

After the war, he did not have enough money to return to his homeland. Mainland China, where the Chinese Communist Party now ruled, and the island of Taiwan, governed by the Republic of China and ruled by the Kuomintang, had fallen into disorder so he stayed in Japan. He pursued different types of work and moved from place to place in the Chugoku region and Kyushu. This was back when there was strong discrimination against people from other countries and A-bomb survivors. Thus, he told others that he spoke a dialect of Japanese because he was from Kyushu.

The turning point in his life arrived in 1960. Mr. Masui married Kiyoko, now 78, who was working alongside him at a beer hall in Hiroshima. The following year, their daughter was born, Mika Kusaka, now 56. He opened a Chinese restaurant downtown, seeking to add further stability to his life, and obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate around this time.

His fried rice and dumplings became popular because he added small twists to them, and his restaurant became a flourishing business. In 1969, he moved his restaurant to a site across the river from the Peace Memorial Park and named it Heiwa-rō with the Chinese character meaning “peace.” After retiring from this restaurant, where he had worked for about 20 years, he acquired Japanese nationality. He joined an around-the-world trip organized by Peace Boat, a non-governmental organization (NGO), and saw scars left by the war in about 40 countries, including Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines.

Takashi Kusaka, 25, Mr. Masui’s first grandchild, whose first name is derived from Mr. Masui’s Taiwanese name, plans to travel abroad on Peace Boat in September and share his grandfather’s A-bomb experience. “To understand other people is the first step for creating a peaceful world,” Mr. Masui said, conveying his hopes. “I’d like my grandson to exchange views and ideas with others, wherever he goes, in place of me.”

Teenagers’ impressions

I would be in tears

It was the first time I listened to the experience of an A-bomb survivor from Taiwan. Mr. Masui was at the mercy of history, and he suffered many hardships, but he still looked happy. If I were in his shoes, I would be in tears, wondering, “Why did I have to experience such a terrible thing? I want to go back to my own country.” I knew about A-bomb survivors from other countries, but I want to view Japanese history with the history of other countries in mind, such as why those people came to Japan. (Hitoha Katsura, 13)

Surprised by Japanese-style education in Taiwan

Mr. Masui said, “It’s important to exchange views with consideration for other people.” I think he said this because he experienced life from the perspective of someone who’s both Taiwanese and Japanese. He also told us about the relationship between Taiwan and Japan from the days before the war to the present. In particular, I was surprised to hear that the Japanese-style education was carried out in Taiwan, especially when it was a Japanese colony. I thought how it’s important to know other people’s viewpoints and widen my perspective in order to help foster mutual understanding. (Anna Ikeda, 16)

(Originally published on April 2, 2018)