Building Bridges: Pauline Baldwin, 59, Canadian interpreter and translator

Sep. 11, 2018

Still clearly recalls state of Hiroshima during period of city’s reconstruction

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

This past spring, in the year marking the 60th anniversary of the unveiling of the Children’s Peace Monument in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, Pauline Baldwin, 59, a Canadian interpreter and translator, completed the English translation of the Japanese book Genbaku no ko no zo, Roku-nen Takegumi no nakamatachi (The Children’s Peace Monument: Friends from the 6th Grade Takegumi “Bamboo Class”). The book was published by Tomiko Kawano, 76, a former classmate of Sadako Sasaki, the girl who died of A-bomb-induced leukemia and became the inspiration for raising the monument. Through her peace activities in Hiroshima, including the many videos of A-bomb survivors’ accounts that Ms. Baldwin has created the English subtitles for, she has developed a deep connection with Hiroshima. Each time she receives a Japanese text for translation, she reads it aloud over and over, in Hiroshima dialect, before she begins to translate the text into English. She stressed, “I believe I need to understand and feel a survivor’s experience as my own, to the extent possible, in order to create a faithful translation and this is why I spend a significant amount of energy on my work.”

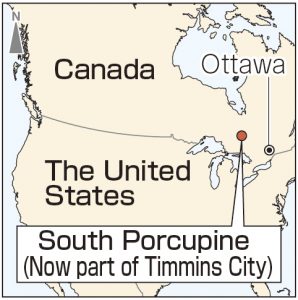

Growing up, she saw, first-hand, the people of Hiroshima moving forward with their lives during the period of reconstruction. Ms. Baldwin was born in South Porcupine (now part of Timmons City) in Ontario, Canada. In August 1960, when she was just a year old, she came to Japan with her family on the cargo-passenger ship "Hikawamaru" when her father, William Baldwin, now 87, was sent here as a Christian missionary of the Anglican Church of Canada. After living in Kyoto for a while, her family moved to Hiroshima in the summer of 1962.

When Ms. Baldwin arrived in Hiroshima, 15 years had passed since the atomic bombing. Still, she observed many traces of the bombing in town. Near her home in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward), she saw many survivors with keloid scars on their faces or hands. Though she and her parents were from Canada, their Caucasian appearance meant that they sometimes became a target for their neighbors’ anger toward the United States, which had dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. At her kindergarten, Ms. Baldwin was called such names as “A-bomb bitch” and “Miss America” and pushed off the top of the slide or the swings and locked in a room by other children. On one occasion, she even broke her arm.

Her father’s work in Hiroshima was not a missionary role; he was involving in helping those who were not receiving adequate support from the government. In particular, he tried hard to help Korean nationals who were living in Japan. Ms. Baldwin still vividly remembers the A-bombed slum area, where she went almost every week with her father. The slum was spread along the banks of the Honkawa River. While her father was busy working, she played with Korean children, and sang songs with them, at a corner near the rows of shacks. Compared to the adults who lived hand to mouth each day, she found the faces of the children there always cheerful. She emphasized, “The smiling faces of children are a sign of hope in any setting.”

After attending an international school in Kobe, Ms. Baldwin went to Victoria University in Canada. She then returned to Hiroshima when she was in her mid-20s and has done various types of work, including jobs as an English teacher at Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School and a reporter for TV and radio programs. Two years ago, she made the English translation of a manga comic book titled Hiroshima’s Revival, a project organized by RCC Broadcasting. This book was also given to Barack Obama, then U.S. president, when he visited Hiroshima. While working as an interpreter and translator, Ms. Baldwin is now also teaching English at universities and vocational schools in the Hiroshima area.

Looking back at her life and its deep roots in Hiroshima, Ms. Baldwin has come to feel that she is following in her parents’ footsteps, though the nature of her work has been different. Her father diligently provided support to others in a foreign land, while her mother, Eleanor Baldwin, 83, was a teacher who was involved in establishing the Hiroshima American School, now known as Hiroshima International School.

When she looks out at the world, Ms. Baldwin finds persistent problems that concern not only incidents of nuclear damage but also cases of conflict and human rights violations and that many people are completely unaware of these issues. With the words “Ignorance is sin” in mind, an expression often used by her mother, she remains determined to face such global issues from Hiroshima, understand them as best she can, and convey them to others as widely as possible.

(Originally published on September 11, 2018)

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

This past spring, in the year marking the 60th anniversary of the unveiling of the Children’s Peace Monument in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, Pauline Baldwin, 59, a Canadian interpreter and translator, completed the English translation of the Japanese book Genbaku no ko no zo, Roku-nen Takegumi no nakamatachi (The Children’s Peace Monument: Friends from the 6th Grade Takegumi “Bamboo Class”). The book was published by Tomiko Kawano, 76, a former classmate of Sadako Sasaki, the girl who died of A-bomb-induced leukemia and became the inspiration for raising the monument. Through her peace activities in Hiroshima, including the many videos of A-bomb survivors’ accounts that Ms. Baldwin has created the English subtitles for, she has developed a deep connection with Hiroshima. Each time she receives a Japanese text for translation, she reads it aloud over and over, in Hiroshima dialect, before she begins to translate the text into English. She stressed, “I believe I need to understand and feel a survivor’s experience as my own, to the extent possible, in order to create a faithful translation and this is why I spend a significant amount of energy on my work.”

Growing up, she saw, first-hand, the people of Hiroshima moving forward with their lives during the period of reconstruction. Ms. Baldwin was born in South Porcupine (now part of Timmons City) in Ontario, Canada. In August 1960, when she was just a year old, she came to Japan with her family on the cargo-passenger ship "Hikawamaru" when her father, William Baldwin, now 87, was sent here as a Christian missionary of the Anglican Church of Canada. After living in Kyoto for a while, her family moved to Hiroshima in the summer of 1962.

When Ms. Baldwin arrived in Hiroshima, 15 years had passed since the atomic bombing. Still, she observed many traces of the bombing in town. Near her home in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward), she saw many survivors with keloid scars on their faces or hands. Though she and her parents were from Canada, their Caucasian appearance meant that they sometimes became a target for their neighbors’ anger toward the United States, which had dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. At her kindergarten, Ms. Baldwin was called such names as “A-bomb bitch” and “Miss America” and pushed off the top of the slide or the swings and locked in a room by other children. On one occasion, she even broke her arm.

Her father’s work in Hiroshima was not a missionary role; he was involving in helping those who were not receiving adequate support from the government. In particular, he tried hard to help Korean nationals who were living in Japan. Ms. Baldwin still vividly remembers the A-bombed slum area, where she went almost every week with her father. The slum was spread along the banks of the Honkawa River. While her father was busy working, she played with Korean children, and sang songs with them, at a corner near the rows of shacks. Compared to the adults who lived hand to mouth each day, she found the faces of the children there always cheerful. She emphasized, “The smiling faces of children are a sign of hope in any setting.”

After attending an international school in Kobe, Ms. Baldwin went to Victoria University in Canada. She then returned to Hiroshima when she was in her mid-20s and has done various types of work, including jobs as an English teacher at Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior and Senior High School and a reporter for TV and radio programs. Two years ago, she made the English translation of a manga comic book titled Hiroshima’s Revival, a project organized by RCC Broadcasting. This book was also given to Barack Obama, then U.S. president, when he visited Hiroshima. While working as an interpreter and translator, Ms. Baldwin is now also teaching English at universities and vocational schools in the Hiroshima area.

Looking back at her life and its deep roots in Hiroshima, Ms. Baldwin has come to feel that she is following in her parents’ footsteps, though the nature of her work has been different. Her father diligently provided support to others in a foreign land, while her mother, Eleanor Baldwin, 83, was a teacher who was involved in establishing the Hiroshima American School, now known as Hiroshima International School.

When she looks out at the world, Ms. Baldwin finds persistent problems that concern not only incidents of nuclear damage but also cases of conflict and human rights violations and that many people are completely unaware of these issues. With the words “Ignorance is sin” in mind, an expression often used by her mother, she remains determined to face such global issues from Hiroshima, understand them as best she can, and convey them to others as widely as possible.

(Originally published on September 11, 2018)