Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Photographic record of the A-bombing

Sep. 4, 2014

Conflicted feelings over duty to take photos

Photographs documenting the atomic bombing are also “witnesses to history” that convey what happens to human beings when nuclear weapons are used. Through the end of 1945, 57 Japanese took at least 2,571 photos related to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima by the U.S. military on August 6, 1945. In particular, the photographs of Yoshito Matsushige (1913-2005) and Masami Onuka (1921-2011) provide a historical record of the devastation immediately after the A-bombing. This article traces the movements of the two photographers and examines what sort of photographs they took amid unprecedented conditions.

Yoshito Matsushige Took photographs on August 6, 1945

True horror impossible to convey even with several thousand photos

Yoshito Matsushige greeted the morning of August 6, 1945, at the Chugoku District Military Headquarters on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle and returned to his home in Midori-machi (now Nishi Midori-machi, Minami Ward), which also housed a barbershop. The previous year he had been officially hired by the Chugoku Shimbun, but he was also a member of the military’s news team.

He is the only person to capture on film graphic shots of citizens and mobilized students in the devastated Hiroshima delta on the day of the atomic bombing. “I was lucky enough to survive. That’s why I was able to take those photographs,” he said.

In his later years he talked with a young reporter on the paper about the events leading up to the five shots he took that day.

After eating breakfast at home, he set off for work by bicycle but turned around just before reaching the Miyuki Bridge to return home to go to the toilet. If he had continued on to the newspaper’s offices, which were then located in Kami-nagarekawa-cho (now Ebisu-cho, Naka Ward), it is likely he would not have survived.

He was at his home, about 2.7 km southeast of the hypocenter, when the atomic bomb was dropped. He described the events that followed in “The Atomic Bombings: A Photographic Record of Hiroshima, Volume 1,” which was published by Asahi Publishing in 1952 after the Allied Occupation of Japan ended.

“When I came to my senses I reached for my waist, and found my camera hanging there.” Mr. Matsushige said he usually kept his Mamiya 6 camera tied around his waist on a leather strap out of “a sense of professionalism” in case he should suddenly need it and because it was his most expensive possession. Luckily his camera was undamaged, so he was able to take pictures.

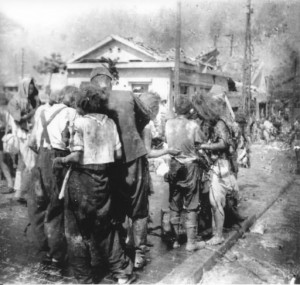

He took his first photos at the west end of the Miyuki Bridge, about 2.2 km from the hypocenter. He described his feelings at that time in the 1952 publication. “Dozens of people who seemed not of this world were moaning and weeping… With rage and sadness, I took two shots. Even now I clearly recall that the viewfinder was clouded by my tears.”

Speaking on behalf of her 98-year-old mother, Sumie, Miyoshi resident Kayo Inoshita, 71, talked about her father. “He never raised his voice at home,” she said. Former photographers who knew Mr. Matsushige uniformly described him as “a gentle person.” It was this nature that prevented him from calmly taking photos.

In the afternoon Mr. Matsushige made his way to Kamiya-cho (now part of Naka Ward), near the hypocenter. There he saw the remains of a streetcar. Inside were the burned bodies of several dozen people piled on top of each other just where they had probably been when they boarded. But the scene was “so dreadful” that he could not take a picture of it.

Mr. Matsushige was among a number of reporters and photographers who documented the A-bombing despite having experienced it themselves. They offered candid descriptions of their conflicted feelings in “Hiroshima: A Special Report,” which was published in 1980.

After taking five photos on the day of the A-bombing, Mr. Matsushige left Hiroshima. His wife was pregnant with their second child, and his injured niece had been brought to their house. They headed for Omishima Island in Ehime Prefecture, where Mr. Matsushige had sent his parents and daughter so they could escape air raids on Hiroshima.

The two shots Mr. Matsushige took at the Miyuki Bridge were first published in the July 6, 1946 edition of “Evening Edition Hiroshima,” a publication put out by a separate company run by the Chugoku Shimbun. The pictures appeared under the headline “Photographs of the century.” The accompanying article stated that an American magazine would reveal the photos to the world and referred to “Life” magazine, but in fact the pictures did not appear in that magazine until they were published in the September 29, 1952 issue under the headline “First Pictures – Atom Blasts through Eyes of Victims.”

Their initial publication in “Evening Edition Hiroshima” took place during the Allied Occupation, when coverage of the atomic bombing was censored by the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces. It is believed that the article was deliberately written in such a way as to get past the censors.

After being published in Japan and then overseas in 1952, the horrible scenes at the Miyuki Bridge became representative photos of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. After his retirement in 1969, Mr. Matsushige recounted his experiences in the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1978 he formed the Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima and collected 285 photos taken by 20 photographers, which he gave to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

He continued recounting his experiences until his death, despite suffering from kidney failure and having to undergo dialysis. His daughter Kayo said that when she urged him to stop out of concern for his health, he simply said, “It’s my duty.”

Reviewing Mr. Matsushige’s accounts of his experiences for this article, in 1981 he addressed the Independent Commission on Disarmament and Security Issues (Palme Commission), which met in Hiroshima. At that time he said, “The five pictures I took and the several thousand other photos that were taken cannot convey the true horror of the atomic bombing.” This is surely the cry of a survivor.

Masami Onuka Took photographs on August 7, 1945

Hesitant to follow orders Feeling guilty upon catching eye of subject

Japan’s sovereignty was restored in 1952 with the end of the Allied Occupation. That summer the cover of the August 6 edition of the “Asahi Graph” magazine featured a headline that read: “First look at A-bomb devastation.” The issue was reprinted several times, and ultimately about 700,000 copies were issued.

At the top of the feature article were three graphic photos, including one of a soldier who was burned all over his body and another of a woman whose back was hideously burned. There were no photo credits, but all three shots were taken by Masami Onuka, a member of the photographic team of the Imperial Japanese Army’s Shipping Command, which was based in Ujina (now part of Minami Ward).

Mr. Onuka was born in what is now Onan-cho in Shimane Prefecture. He was employed at a photography studio in Miyoshi in northern Hiroshima Prefecture. He became a member of the photographic team in 1941. He was also sent to the front lines in the South Pacific but returned safely.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was receiving instructions in the front courtyard of the Gaisenkan, the building in Ujina that housed the offices of the shipping command. Mr. Onuka’s story is among the accounts of those who photographed the destruction caused by the atomic bombing that were included in Volume 5 of “Record of the A-Bomb Disaster” issued by the City of Hiroshima in 1971. “Suddenly there was an intense yellow light right in front of my eyes and then a tremendous roar that resonated in my belly,” Mr. Onuka said.

At the orders of his superior, that day he went in search of his 60-year-old mother, Makino, who lived in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward). There was no one at home, so he headed for his sister’s house in Hirano-machi (now part of Naka Ward), but it was in flames and he could not get inside. “I had seen a lot of terrible things on the front lines on Bougainville, but this was much worse.”

He was ordered to take photos on August 7. A temporary field hospital had been set up at the army quarantine station on Ninoshima Island off Ujina. “On the order of an army doctor, I took a lot of photos, including shots of people who had been horribly burned and dead bodies that had been gathered in one place.”

In 1985, in response to a request from Yoshito Matsushige, eight photographers, including Mr. Onuka, gathered for a videotaped interview with the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. In the interview Mr. Onuka described how he felt about having been ordered to take photos.

“It was an order, but I hesitated,” he said. “When taking the photos, I would catch the eyes [of the wounded]. It was upsetting, and I couldn’t bring myself to take their pictures. So the army doctor ordered me to do it. I took a photo of the soldier who was unburned where his bellyband had been. But when our eyes met I felt guilty.”

He continued to take photos from August 7 on using a view camera, a Mamiyaflex and a Leica. On August 8, he accompanied members of the Kempeitai military police to relief stations in Hijiyama and Danbara (now parts of Minami Ward). He also took photos at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Fukuya department store (in what is now Naka Ward). Everywhere he went, he looked for his mother, but he was unable to find her.

At the end of the war the negatives of Mr. Onuka’s photographs documenting the devastation caused by the A-bombing met an unexpected fate: they were incinerated along with confidential documents.

But Yotsugi Kawahara, another member of the Shipping Command’s photographic team, had secretly kept 23 prints. (Mr. Kawahara died in 1972 at the age of 49.) Keisuke Misonoo, an army doctor who came to Hiroshima on August 14 to conduct a survey for the Army Ministry, kept 52 photos taken by the photographic team. (Mr. Misonoo died in 1995 at the age of 82.) The existence of these prints was discovered in 2005.

After the war Mr. Onuka opened a photography studio in Kawamoto, Shimane Prefecture, which adjoins his hometown, and had a family. The studio was taken over by his son Hidenori, 64.

From a young age he was accustomed to seeing his father quietly taking photos of local residents at weddings and on other special occasions. “My father never said much to us about what had happened in Hiroshima,” he said.

Mr. Onuka did not refer to himself as a photographer of the atomic bombing, but when the Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima was formed in 1978, he joined. In the 1990s, at the request of a local elementary school, he described his experiences to the students.

Until his later years he went to Hiroshima every August 6 to attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony in memory of his mother, whose remains were never found.

As part of a survey conducted by the Health and Welfare Ministry to mark the 50th anniversary of the A-bombing in 1995, Mr. Onuka described the devastation he saw in Hiroshima while taking photographs and searching for his mother.

“I saw many victims in a miserable state: a boy crying in pain and begging me for water, a half-naked schoolgirl. When I looked at them through the viewfinder I couldn’t maintain my usual composure.” He also wrote, “I kept calling my mother’s name, but in the end I couldn’t find her.” He closed by saying, “I think my mother died so that I could live.”

Photo captions (Originally published on August 4, 2014)