Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: The “Value” of Plutonium

Jun. 1, 2016

by Yoko Yamamoto and Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writers

Plutonium is a nuclear substance that is artificially produced in a nuclear reactor. Japan has sought to make use of plutonium for many years, as a resource for the peaceful use of nuclear energy. However, holding a large amount of this material, which can be used to make nuclear weapons, could also fuel nuclear proliferation. The Chugoku Shimbun considers the “value” of plutonium from the village of Rokkasho, in Aomori Prefecture, where a commercial reprocessing plant is being pursued, and Sellafield, in the United Kingdom, a plant now reprocessing spent nuclear fuel from Japan.

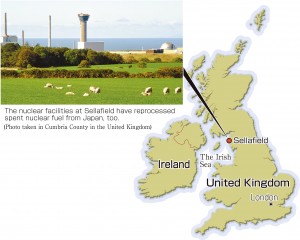

In the early morning, local residents walk their dogs along the beach which faces the Irish Sea. The Sellafield site is located in a corner of the Lake District, in the United Kingdom. This is considered the home of the well-known picture book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit. However, years of radioactive discharges from the Sellafield reprocessing plant, which stands on hilly land, has spread contamination to the seashore and the Irish Sea. And Japan’s nuclear policies are intimately tied to Sellafield.

Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment (CORE) is a citizens’ group that has monitored radioactive contamination in the district since 1980. Jean McSorley, 56, who has been a member of CORE since its inception, explains that contamination from Sellafield has been found on most of the British coastlines.

Following World War II, Sellafield grew as a center of nuclear facilities, mainly producing plutonium for the development of nuclear weapons. The backbone of the site is the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant, or THORP, a large-scale nuclear fuel reprocessing plant which began operations in 1994. Japanese electric power companies covered some of the construction costs and Sellafield undertook the disposal of spent nuclear fuel from Japan, which is why it has been referred to as “Japan’s plant.”

In 1957, a fire broke out in the plutonium production reactor, used in the making of nuclear weapons. Nuclear fuel melted, resulting in a serious accident that ranked at a level 5 in severity, equal to the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the United States in 1979. Moreover, the massive release of radioactive liquid waste from the reprocessing plant, which persisted until the 1980s, spread contamination to other countries through the Irish Sea. This created the unusual situation where the Irish government was demanding that the Sellafield plant be closed. A survey conducted in the Sellafield area revealed that the incidence of leukemia among local children is about ten times the national average.

In 1994, when the British government decided to halt use of the fast-breeder reactor due to economic concerns, THORP ironically began operating. But having served to reprocess nuclear fuels from Japan and Germany, THORP is expected to be shut down in 2018 because of economic inefficiency.

As a result, about 120 tons of plutonium, the largest amount of this substance in the world, is now stored in the United Kingdom, with about 20 tons of it from Japan. While the British government hopes to recycle this plutonium for continuous use as fuel, it has no concrete plan for using it at nuclear power plants in that nation. John Large, a nuclear safety consultant in the United Kingdom, pointed out the possibility of this surplus plutonium coming under terrorist attack and said that terrorists could achieve their aim through the use of a “dirty bomb,” which would spread plutonium through an explosion, even if they were unable to produce a nuclear weapon.

The United Kingdom is now accelerating its technological efforts to “consume” plutonium. The National Nuclear Laboratory (NNL) is pursuing research on a way of storing plutonium safely by applying high pressure and temperature. Together with the NNL and British universities, nuclear power plant companies are moving forward with plans to commercialize a fast reactor which can be fueled using plutonium.

The United Kingdom is confronted by plutonium’s “negative legacy”: it has nowhere to go and there is no end in sight. Ms. McSorley, who has paid a visit to village of Rokkasho, says that Japan, which has already experienced the atomic bombings and the nuclear accident in Fukushima, should not seek to operate a reprocessing plant which would generate a large amount of nuclear material.

If the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho operates at full capacity, it is expected that this facility can separate up to eight tons of plutonium per year. There is a danger that the surplus will increase rapidly, beyond the existing 47 tons. Even though Japan accepts inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and strictly controls these nuclear materials, there is strong concern among the international community that Japan’s privilege to reprocess and enrich uranium could potentially encourage other nations to insist on holding the same right.

However, the NPT guarantees that nations have the “inalienable right” to the peaceful use of nuclear energy in exchange for agreeing never to acquire nuclear weapons. The treaty itself does not regulate reprocessing or uranium enrichment.

The international community is waiting for the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty to be implemented. This treaty aims to enhance the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation system by inhibiting the production of specific materials, including highly enriched uranium for nuclear weapons or plutonium.

In 1995, a special committee to conclude the treaty was first established at the Geneva-based Conference on Disarmament, but substantive negotiations have not taken place. And even if the treaty is concluded, it would not serve to control fissile materials produced for civilian use, which can be used to produce nuclear arms. Thus, there is growing concern over this current state of affairs from the perspective of the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons materials.

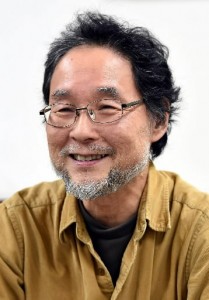

Japanese policy involving the nuclear fuel cycle has persisted without a long-term vision. Masafumi Takubo, who heads a website on nuclear issues, is familiar with the situation surrounding plutonium, both inside and outside Japan. We asked his views on the background and problems involving this nation’s nuclear energy policy.

What do you think of Japan’s policy, in deeming plutonium a “resource”?

Plutonium is troublesome nuclear waste. A few years ago, the United Kingdom suggested that they dispose of Japan’s plutonium held there, along with U.K. plutonium, if they could come to an agreement. This means that Japan would have to pay for such services. The market price for plutonium is now below zero because producing fuel with uranium is less costly.

After 1974, when India conducted a nuclear test using separated plutonium under the pretext of peaceful use, the United States stopped reprocessing spent fuel because of concerns over nuclear proliferation. The United States reversed its policy and demanded that other nations also stop reprocessing spent fuel.

How has this impacted nuclear proliferation?

After the terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, there was fear as people thought, “What if it had been nuclear weapons?” This heightened concerns over nuclear proliferation. The idea that nuclear material must not fall into the hands of terrorists spread internationally. Last spring, the Nuclear Security Summit, held in the Netherlands, issued a statement demanding that nuclear materials involved in making nuclear arms be “mimimized.”

If the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho, which can extract plutonium equivalent to 1,000 nuclear weapons per year, goes into operation, it will be the only facility on a commercial scale in a non-nuclear-weapon state. This could set a bad precedent, but concern over the issue among the Japanese people is low.

Why doesn’t Japan change its policy?

The policy concerning the nuclear fuel cycle has already collapsed. Nevertheless, there are advocates of this policy because the spent fuel pools at the nuclear power plants in Japan are approaching their capacity and we have no choice but to transport spent fuel to the village of Rokkasho.

The solution is “dry cask storage,” in which spent fuel is housed in metal cylinders located inside and outside the nuclear power plant sites and cooled by air. This would be an alternative to transporting the spent fuel to Rokkasho. More than one member of the Nuclear Regulation Authority has also pointed out that this would be much safer than a storage pool. It would be better for the areas where nuclear plants are located.

What role do you think Hiroshima and Nagasaki can play?

We can’t win the understanding of others if we appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons while continuing this policy of amassing plutonium. First of all, to help advance a world without nuclear weapons, Japan should abandon its plan to run a reprocessing plant. If the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki raise their voices against this plan, this will have an important influence.

Profile

Masafumi Takubo

Born in 1951 in the city of Imabari, Ehime Prefecture, Mr. Takubo led international affairs for the Japan Congress against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, and became an instructor of peace studies at Hosei University. He heads up the website “Kakujoho” and is an analyst of nuclear power and policy. He is also a member of the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

In March, at a regular meeting of the prefectural assembly, Shingo Mimura, the governor of Aomori Prefecture, responded to questions. “Nuclear energy and the nuclear fuel cycle are important to Japan, and I see them as firm national strategies,” he said. Since the time a former governor agreed to host nuclear facilities in the village of Rokkasho 30 years ago, Aomori Prefecture has been aligned with the nation’s nuclear policy.

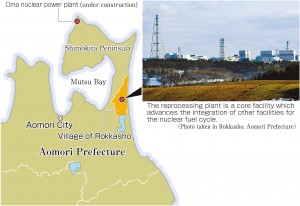

Rokkasho Village stretches along the coast of the Pacific Ocean on the Shimokita Peninsula in Aomori Prefecture. A vast 740-hectare site surrounded by barbed-wire fences is dotted with facilities for the nuclear fuel cycle. The date for completing the reprocessing plant, where plutonium is extracted from spent nuclear fuel, has been postponed more than 20 times. It is now scheduled to begin operations in March 2016. However, the fast-breeder reactor Monju, located in Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture, which was intended to burn the plutonium extracted by this reprocessing activity, has not been operating since an accident in 1995 which involved a sodium leak.

The capacity of the reprocessing plant is 800 tons of spent nuclear fuel per year, from which about 8 tons of plutonium can be extracted, equivalent to more than 1000 atomic bombs. Several inspectors from the IAEA are already stationed at these facilities around the clock. They monitor the stockpile of plutonium extracted from past tests. A spokesperson from the Japan Nuclear Fuel Industry, which oversees this activity, said, “The plant has an ‘on-site laboratory’ and inspections are performed in the most stringent way yet seen in the world.”

The amount of spent fuel and radioactive waste being brought to Rokkasho from across Japan continues to grow, while the reprocessing cycle remains inactive. If this policy is finally abandoned, the spent fuel would instantly change from “resources” into “waste.” Aomori Prefecture and the village of Rokkasho is seeking to discourage the country from taking this step by warning that the spent fuel would be returned to each nuclear power plant.

Koji Asaishi, 74, a lawyer, leads a lawsuit filed by a group of 10,000 plaintiffs who seek to stop the nuclear fuel cycle. “The central government and local governments are co-conspirators,” he said. The Basic Energy Plan that was adopted by the Abe administration last spring, without adequate debate, includes “promoting” the nuclear fuel cycle and there are now few opportunities to discuss the pros and cons of this policy. “We will continue questioning this through the court system,” Mr. Asaishi said.

However, supporters of the opposition movement have aged over the past 30 years, and the involvement of younger generations has been limited. Drying kelp on the beach, Nobuo Taneichi, 80, part of the group of plaintiffs, said, “We won’t stop fighting against nuclear fuel. This is my role.” The number of villagers who openly express their opposition is small, but their voices have been heard at every election for mayor when an opposition candidate runs for office. Still, when they imagine a time when no opposition remains, anxiety rises: “Nuclear materials from this plant might be used in war one day.”

Syoko Sawai, 61, another plaintiff, works for the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center in Tokyo. Pointing to plans at the Oma nuclear power plant to use plutonium-uranium mixed oxide (MOX) fuel for the whole reactor core, she warned, “Shimokita Peninsula could become a center for plutonium.”

Even within the movement against nuclear power plants to date, the typical reaction of many people to the problems of nuclear reprocessing and plutonium is: “I don’t know about this very well.” Steeling herself, Ms. Sawai said, “We have to make these problems involving plutonium known to the world, conveying this information to a wide range of citizens, just like people are showing greater concern over restarting nuclear plants, which is an issue that’s closer to them.”

How has the city of Hiroshima faced the problem of plutonium? It is hard to say that efforts to abolish nuclear weapons and oppose the reprocessing of spent fuel have had a unified front.

Aileen Mioko Smith, 64, the head of Green Action, an NGO in Kyoto which opposes the use of plutonium, clearly recalls her experience in New York in 2005 during the time of the Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

She took part in a demonstration with banners that bore slogans like “No more plutonium” and “Stop Rokkasho.” However, while activists from other nations took interest and helped carry signs, Japanese people who were appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons showed little reaction. She thought, “Hiroshima should be angry at Japan for producing plutonium.” She still feels some discomfort over that experience.

The late Ichiro Moritaki, the former head of the Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs (Gensuikin), stressed that “The human race cannot coexist with nuclear weapons or nuclear energy.” In 1989, he called for 10,000 participants for a rally in the village of Rokkasho and stood at the head of the human chain which surrounded the nuclear facilities there. In 1972, Gensuikin decided to “oppose nuclear power plants, which bring utter destruction and radioactive contamination to the environment, as well as nuclear facilities for reprocessing spent fuel.”

However, Yukio Yokohara, 74, director of the Hiroshima Congress against A- and H-Bombs, looked back and said, “We had the right idea, but we couldn’t get a campaign going from Hiroshima.”

In 1987, A-bomb survivors and sufferers of nuclear tests and nuclear accidents gathered in New York for the World Convention of Victims of Radiation. Mr. Yokohara was pressed by Western participants who said that Japan was a quasi-nuclear power and that Japan was forcing used fuel and contamination upon the United Kingdom and France. Shocked by this experience, he learned about the problems involving reprocessing and joined a lawsuit, as a private citizen, to halt Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle. Still, he said, “Many people even in Gensuikin didn’t like linking nuclear abolition with this problem.”

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If the project goes as planned, the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho will begin operations next spring. “Are we going to accept becoming a plutonium society against the global trend?” said Mr. Yokohara. “In the antinuclear movement, the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are questioned as to whether we will be able to create a movement which not only conveys our own memories of the atomic bombings but also expresses opposition to the nuclear fuel cycle.”

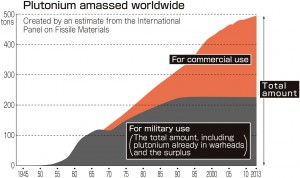

At a presentation held in Washington D.C. last fall, Zia Mian, 53, a physicist at Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security, pointed at a graph and said that plutonium for commercial purposes could be used for nuclear weapons, and that “a world without nuclear weapons” could only be realized if these materials are not manufactured. Mr. Mian served as co-chair of the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), which consists of experts from 18 nations.

The graph showed that the amount of plutonium stock for commercial use is growing. It is clear that Mr. Mian’s criticism, though he mentioned no names, was targeting Japan, which has been amassing a large stockpile of plutonium for no apparent purpose.

Among the non-nuclear powers, reprocessing spent fuel to extract plutonium is permitted only in Japan. The time limit for this, stipulated in the current Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy, is 2018. Japan, where the nuclear fuel cycle policy is still uncertain, could be forced to “withdraw” due to outside pressure.

At a session of the Liberal Democratic Party held in late February, Taro Kono, a member of the Lower House, said to an official of the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, “You should speak sincerely with Aomori Prefecture and tell them that the nation’s policy may change.” Mr. Kono believes that “The cycle has failed, but it never stops. All the government can do is apologize for the errors and start reviewing Japan’s nuclear energy policy from scratch.”

Mr. Kono was told by an executive of an electric power company, which shuns heavy expenses, “Be assured that the plant in Rokkasho will not operate for the time being.” After the nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, Richard Armitage, the former U.S. deputy secretary of state, told Mr. Kono that he wants to see a halt to reprocessing in Japan.

The United States is concerned that some nations, such as South Korea and South Africa, will seek the right to engage in reprocessing, following Japan’s example. Mr. Kono said, “Japan should stop its reprocessing efforts and insist that other countries not get involved in reprocessing.” He laments the fact that, under current circumstances, the A-bombed nation could be paving the way for nuclear proliferation.

The international community holds deep doubts over Japan. The United States has pledged to protect Japan, its ally, with the U.S. nuclear umbrella, thinking that, otherwise, Japan might seek to build its own nuclear arsenal to rival China and North Korea. But, in fact, unless Japan should quit the NPT, this is an unrealistic concern. Still, it is undeniable that holding a large amount of plutonium stocks and repeated remarks by some conservative politicians that Japan should become a “nuclear-armed-nation” cast a shadow over Japan’s reputation.

How will Japan manage its surplus plutonium? This has become a major concern which severely tests the management skills of those in charge. And yet a private-sector corporation, financed by the electric power companies, is operating the whole business of the nuclear fuel cycle. Even among proponents of the nuclear fuel cycle, there are strong calls for the Japanese government to assume full responsibility for the nation’s surplus plutonium.

Saburo Kikuchi, director of the Radwaste and Decommissioning Center, said, “The cycle should be nationalized.” He has been the Japanese delegate to an international meeting on reprocessing and was even dubbed “Mr. Plutonium.”

Mr. Kikuchi headed the classified project where plutonium returned from France was carried to Japan by ship. The direction from the U.S. military instructed Japan to submerge the ship in the sea if it came under attack. Mr. Kikuchi, who had the final authority, keenly felt the weight of his responsibility, as if the ship was carrying an atomic bomb.

Drawn by a fait accompli, Japan is seeking to become deeply involved in the nuclear fuel cycle. If its sense of responsibility and initiative as a nation lacks strength, Japan will have no persuasive power to insist on non-proliferation or the prevention of nuclear terrorism.

Keywords

Plutonium

An element that rarely exists in nature, plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,000 years. When a uranium fuel rod is burned in a nuclear reactor, uranium-238, which is an element in uranium fuel and does not fission, absorbs neutrons and the new element “plutonium” is produced. Plutonium can be extracted by reprocessing spent nuclear fuel and become material for nuclear weapons or fast breeder reactors. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) states that eight kilograms of plutonium is needed to manufacture a nuclear weapon, though some experts believe that a lesser amount is sufficient.

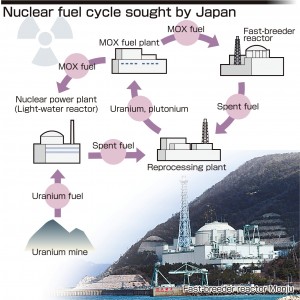

Nuclear fuel cycle

A system in which spent nuclear fuel from nuclear power plants is reprocessed and the extracted uranium and plutonium are combined to form mixed oxide (MOX) fuel for reuse. A core fast-breeder reactor is called a “dream reactor” because it produces more plutonium than it consumes in fuel. However, the prototype fast-breeder reactor Monju has experienced a series of setbacks, and the Nuclear Regulation Authority issued an order to effectively halt the operation of Monju in May 2013. Problems include economic efficiency and safety concerns involving pluthermal (plutonium-thermal) power generation, where MOX fuel is burned at standard nuclear power plants.

Japan-U.S. Atomic Agreement

In line with this agreement, which Japan made with the United States in 1955, Japan was provided with enriched uranium and nuclear energy development then proceeded at full swing. A revised agreement in 1968 advanced the launch of commercial nuclear power plants. Under the agreement, U.S. consent is required to reprocess spent nuclear fuel, extract plutonium, and implement the nuclear fuel cycle policy. In the wake of India’s nuclear test in 1974, the United States strengthened its policy regarding the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, but agreed to Japan’s commercial reprocessing based on the existing Japan-U.S. Atomic Agreement. The next negotiations for revision of the agreement are due to conclude in 2018.

■Major incidents and influences on Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle policy

December 1953: U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower proclaims the idea of “Atoms for Peace” at the United Nations.

November 1955: Japan and the U.S. sign the Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy, an agreement that is central to providing Japan with enriched uranium.

July 1966: The Tokai nuclear power plant begins operations, marking Japan’s first use of commercial nuclear energy.

February 1970: Japan signs the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

June 1971: Construction of a reprocessing facility begins in Tokaimura in Ibaraki Prefecture.

May 1974: India conducts its first nuclear test.

April 1977: The U.S. announces a change in its nuclear non-proliferation policy, which includes indefinitely postponing commercial reprocessing in the country.

January 1981: The reprocessing facility in Tokaimura begins full-scale operations.

November 1984: A Japanese ship, the Seishin-maru, arrives back at port in Japan with 280 kilograms of plutonium returned from France.

April 1985: The governor of Aomori Prefecture accepts hosting facilities for the nuclear fuel cycle in the village of Rokkasho.

April 1986: A severe accident occurs at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

November 1987: Japan and the U.S. sign the current Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy. (It takes effect in July 1988.)

January 1993: A Japanese ship, the Akatsuki-maru, returns from France, arriving back at port in Japan with about 1.7 tons of plutonium.

January 1994: The U.K reprocessing plant THORP begins operations.

December 1995: The fast-breeder reactor Monju suffers a sodium-leak accident.

February 1997: The government approves “pluthermal,” or plutonium-thermal, power generation at Cabinet meetings.

February 1998: The French government officially decides to decommission the fast-breeder reactor Superphénix.

March 2006: The reprocessing plant in Rokkasho begins active tests to extract plutonium.

December 2009: The Genkai Nuclear Power Unit No. 3 of the Kyushu Electric Power Company is the first to introduce full-scale pluthermal.

March 2014: At the Nuclear Security Summit held in the Netherlands, a statement which calls for reductions in stockpiles of nuclear materials is adopted. Japan announces that about 300 kilograms of plutonium will be returned to the U.S.

March 2016: The reprocessing plant in Rokkasho is scheduled to begin operations.

(Originally published on March 28, 2015)

Plutonium is a nuclear substance that is artificially produced in a nuclear reactor. Japan has sought to make use of plutonium for many years, as a resource for the peaceful use of nuclear energy. However, holding a large amount of this material, which can be used to make nuclear weapons, could also fuel nuclear proliferation. The Chugoku Shimbun considers the “value” of plutonium from the village of Rokkasho, in Aomori Prefecture, where a commercial reprocessing plant is being pursued, and Sellafield, in the United Kingdom, a plant now reprocessing spent nuclear fuel from Japan.

U.K. reprocessing plant spreads contamination

In the early morning, local residents walk their dogs along the beach which faces the Irish Sea. The Sellafield site is located in a corner of the Lake District, in the United Kingdom. This is considered the home of the well-known picture book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit. However, years of radioactive discharges from the Sellafield reprocessing plant, which stands on hilly land, has spread contamination to the seashore and the Irish Sea. And Japan’s nuclear policies are intimately tied to Sellafield.

Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment (CORE) is a citizens’ group that has monitored radioactive contamination in the district since 1980. Jean McSorley, 56, who has been a member of CORE since its inception, explains that contamination from Sellafield has been found on most of the British coastlines.

Japanese companies support construction

Following World War II, Sellafield grew as a center of nuclear facilities, mainly producing plutonium for the development of nuclear weapons. The backbone of the site is the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant, or THORP, a large-scale nuclear fuel reprocessing plant which began operations in 1994. Japanese electric power companies covered some of the construction costs and Sellafield undertook the disposal of spent nuclear fuel from Japan, which is why it has been referred to as “Japan’s plant.”

In 1957, a fire broke out in the plutonium production reactor, used in the making of nuclear weapons. Nuclear fuel melted, resulting in a serious accident that ranked at a level 5 in severity, equal to the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in the United States in 1979. Moreover, the massive release of radioactive liquid waste from the reprocessing plant, which persisted until the 1980s, spread contamination to other countries through the Irish Sea. This created the unusual situation where the Irish government was demanding that the Sellafield plant be closed. A survey conducted in the Sellafield area revealed that the incidence of leukemia among local children is about ten times the national average.

In 1994, when the British government decided to halt use of the fast-breeder reactor due to economic concerns, THORP ironically began operating. But having served to reprocess nuclear fuels from Japan and Germany, THORP is expected to be shut down in 2018 because of economic inefficiency.

Fears of a terrorist attack

As a result, about 120 tons of plutonium, the largest amount of this substance in the world, is now stored in the United Kingdom, with about 20 tons of it from Japan. While the British government hopes to recycle this plutonium for continuous use as fuel, it has no concrete plan for using it at nuclear power plants in that nation. John Large, a nuclear safety consultant in the United Kingdom, pointed out the possibility of this surplus plutonium coming under terrorist attack and said that terrorists could achieve their aim through the use of a “dirty bomb,” which would spread plutonium through an explosion, even if they were unable to produce a nuclear weapon.

The United Kingdom is now accelerating its technological efforts to “consume” plutonium. The National Nuclear Laboratory (NNL) is pursuing research on a way of storing plutonium safely by applying high pressure and temperature. Together with the NNL and British universities, nuclear power plant companies are moving forward with plans to commercialize a fast reactor which can be fueled using plutonium.

The United Kingdom is confronted by plutonium’s “negative legacy”: it has nowhere to go and there is no end in sight. Ms. McSorley, who has paid a visit to village of Rokkasho, says that Japan, which has already experienced the atomic bombings and the nuclear accident in Fukushima, should not seek to operate a reprocessing plant which would generate a large amount of nuclear material.

NPT does not regulate reprocessing

If the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho operates at full capacity, it is expected that this facility can separate up to eight tons of plutonium per year. There is a danger that the surplus will increase rapidly, beyond the existing 47 tons. Even though Japan accepts inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and strictly controls these nuclear materials, there is strong concern among the international community that Japan’s privilege to reprocess and enrich uranium could potentially encourage other nations to insist on holding the same right.

However, the NPT guarantees that nations have the “inalienable right” to the peaceful use of nuclear energy in exchange for agreeing never to acquire nuclear weapons. The treaty itself does not regulate reprocessing or uranium enrichment.

The international community is waiting for the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty to be implemented. This treaty aims to enhance the nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation system by inhibiting the production of specific materials, including highly enriched uranium for nuclear weapons or plutonium.

In 1995, a special committee to conclude the treaty was first established at the Geneva-based Conference on Disarmament, but substantive negotiations have not taken place. And even if the treaty is concluded, it would not serve to control fissile materials produced for civilian use, which can be used to produce nuclear arms. Thus, there is growing concern over this current state of affairs from the perspective of the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons materials.

Interview with Masafumi Takubo, head of the website “Kakujoho” (Nuclear Information)

Japanese policy involving the nuclear fuel cycle has persisted without a long-term vision. Masafumi Takubo, who heads a website on nuclear issues, is familiar with the situation surrounding plutonium, both inside and outside Japan. We asked his views on the background and problems involving this nation’s nuclear energy policy.

What do you think of Japan’s policy, in deeming plutonium a “resource”?

Plutonium is troublesome nuclear waste. A few years ago, the United Kingdom suggested that they dispose of Japan’s plutonium held there, along with U.K. plutonium, if they could come to an agreement. This means that Japan would have to pay for such services. The market price for plutonium is now below zero because producing fuel with uranium is less costly.

After 1974, when India conducted a nuclear test using separated plutonium under the pretext of peaceful use, the United States stopped reprocessing spent fuel because of concerns over nuclear proliferation. The United States reversed its policy and demanded that other nations also stop reprocessing spent fuel.

How has this impacted nuclear proliferation?

After the terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, there was fear as people thought, “What if it had been nuclear weapons?” This heightened concerns over nuclear proliferation. The idea that nuclear material must not fall into the hands of terrorists spread internationally. Last spring, the Nuclear Security Summit, held in the Netherlands, issued a statement demanding that nuclear materials involved in making nuclear arms be “mimimized.”

If the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho, which can extract plutonium equivalent to 1,000 nuclear weapons per year, goes into operation, it will be the only facility on a commercial scale in a non-nuclear-weapon state. This could set a bad precedent, but concern over the issue among the Japanese people is low.

Why doesn’t Japan change its policy?

The policy concerning the nuclear fuel cycle has already collapsed. Nevertheless, there are advocates of this policy because the spent fuel pools at the nuclear power plants in Japan are approaching their capacity and we have no choice but to transport spent fuel to the village of Rokkasho.

The solution is “dry cask storage,” in which spent fuel is housed in metal cylinders located inside and outside the nuclear power plant sites and cooled by air. This would be an alternative to transporting the spent fuel to Rokkasho. More than one member of the Nuclear Regulation Authority has also pointed out that this would be much safer than a storage pool. It would be better for the areas where nuclear plants are located.

What role do you think Hiroshima and Nagasaki can play?

We can’t win the understanding of others if we appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons while continuing this policy of amassing plutonium. First of all, to help advance a world without nuclear weapons, Japan should abandon its plan to run a reprocessing plant. If the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki raise their voices against this plan, this will have an important influence.

Profile

Masafumi Takubo

Born in 1951 in the city of Imabari, Ehime Prefecture, Mr. Takubo led international affairs for the Japan Congress against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, and became an instructor of peace studies at Hosei University. He heads up the website “Kakujoho” and is an analyst of nuclear power and policy. He is also a member of the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Village of Rokkasho warns that “resources” will turn to “waste” if policy shifts

In March, at a regular meeting of the prefectural assembly, Shingo Mimura, the governor of Aomori Prefecture, responded to questions. “Nuclear energy and the nuclear fuel cycle are important to Japan, and I see them as firm national strategies,” he said. Since the time a former governor agreed to host nuclear facilities in the village of Rokkasho 30 years ago, Aomori Prefecture has been aligned with the nation’s nuclear policy.

Completion postponed more than 20 times

Rokkasho Village stretches along the coast of the Pacific Ocean on the Shimokita Peninsula in Aomori Prefecture. A vast 740-hectare site surrounded by barbed-wire fences is dotted with facilities for the nuclear fuel cycle. The date for completing the reprocessing plant, where plutonium is extracted from spent nuclear fuel, has been postponed more than 20 times. It is now scheduled to begin operations in March 2016. However, the fast-breeder reactor Monju, located in Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture, which was intended to burn the plutonium extracted by this reprocessing activity, has not been operating since an accident in 1995 which involved a sodium leak.

The capacity of the reprocessing plant is 800 tons of spent nuclear fuel per year, from which about 8 tons of plutonium can be extracted, equivalent to more than 1000 atomic bombs. Several inspectors from the IAEA are already stationed at these facilities around the clock. They monitor the stockpile of plutonium extracted from past tests. A spokesperson from the Japan Nuclear Fuel Industry, which oversees this activity, said, “The plant has an ‘on-site laboratory’ and inspections are performed in the most stringent way yet seen in the world.”

The amount of spent fuel and radioactive waste being brought to Rokkasho from across Japan continues to grow, while the reprocessing cycle remains inactive. If this policy is finally abandoned, the spent fuel would instantly change from “resources” into “waste.” Aomori Prefecture and the village of Rokkasho is seeking to discourage the country from taking this step by warning that the spent fuel would be returned to each nuclear power plant.

Koji Asaishi, 74, a lawyer, leads a lawsuit filed by a group of 10,000 plaintiffs who seek to stop the nuclear fuel cycle. “The central government and local governments are co-conspirators,” he said. The Basic Energy Plan that was adopted by the Abe administration last spring, without adequate debate, includes “promoting” the nuclear fuel cycle and there are now few opportunities to discuss the pros and cons of this policy. “We will continue questioning this through the court system,” Mr. Asaishi said.

Limited involvement from younger generations

However, supporters of the opposition movement have aged over the past 30 years, and the involvement of younger generations has been limited. Drying kelp on the beach, Nobuo Taneichi, 80, part of the group of plaintiffs, said, “We won’t stop fighting against nuclear fuel. This is my role.” The number of villagers who openly express their opposition is small, but their voices have been heard at every election for mayor when an opposition candidate runs for office. Still, when they imagine a time when no opposition remains, anxiety rises: “Nuclear materials from this plant might be used in war one day.”

Syoko Sawai, 61, another plaintiff, works for the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center in Tokyo. Pointing to plans at the Oma nuclear power plant to use plutonium-uranium mixed oxide (MOX) fuel for the whole reactor core, she warned, “Shimokita Peninsula could become a center for plutonium.”

Even within the movement against nuclear power plants to date, the typical reaction of many people to the problems of nuclear reprocessing and plutonium is: “I don’t know about this very well.” Steeling herself, Ms. Sawai said, “We have to make these problems involving plutonium known to the world, conveying this information to a wide range of citizens, just like people are showing greater concern over restarting nuclear plants, which is an issue that’s closer to them.”

Reprocessing problem draws scant attention in Hiroshima

How has the city of Hiroshima faced the problem of plutonium? It is hard to say that efforts to abolish nuclear weapons and oppose the reprocessing of spent fuel have had a unified front.

Aileen Mioko Smith, 64, the head of Green Action, an NGO in Kyoto which opposes the use of plutonium, clearly recalls her experience in New York in 2005 during the time of the Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

She took part in a demonstration with banners that bore slogans like “No more plutonium” and “Stop Rokkasho.” However, while activists from other nations took interest and helped carry signs, Japanese people who were appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons showed little reaction. She thought, “Hiroshima should be angry at Japan for producing plutonium.” She still feels some discomfort over that experience.

The late Ichiro Moritaki, the former head of the Japan Congress against A- and H-Bombs (Gensuikin), stressed that “The human race cannot coexist with nuclear weapons or nuclear energy.” In 1989, he called for 10,000 participants for a rally in the village of Rokkasho and stood at the head of the human chain which surrounded the nuclear facilities there. In 1972, Gensuikin decided to “oppose nuclear power plants, which bring utter destruction and radioactive contamination to the environment, as well as nuclear facilities for reprocessing spent fuel.”

However, Yukio Yokohara, 74, director of the Hiroshima Congress against A- and H-Bombs, looked back and said, “We had the right idea, but we couldn’t get a campaign going from Hiroshima.”

In 1987, A-bomb survivors and sufferers of nuclear tests and nuclear accidents gathered in New York for the World Convention of Victims of Radiation. Mr. Yokohara was pressed by Western participants who said that Japan was a quasi-nuclear power and that Japan was forcing used fuel and contamination upon the United Kingdom and France. Shocked by this experience, he learned about the problems involving reprocessing and joined a lawsuit, as a private citizen, to halt Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle. Still, he said, “Many people even in Gensuikin didn’t like linking nuclear abolition with this problem.”

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If the project goes as planned, the reprocessing plant in Rokkasho will begin operations next spring. “Are we going to accept becoming a plutonium society against the global trend?” said Mr. Yokohara. “In the antinuclear movement, the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are questioned as to whether we will be able to create a movement which not only conveys our own memories of the atomic bombings but also expresses opposition to the nuclear fuel cycle.”

Japan holds a large surplus of plutonium

At a presentation held in Washington D.C. last fall, Zia Mian, 53, a physicist at Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security, pointed at a graph and said that plutonium for commercial purposes could be used for nuclear weapons, and that “a world without nuclear weapons” could only be realized if these materials are not manufactured. Mr. Mian served as co-chair of the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), which consists of experts from 18 nations.

The graph showed that the amount of plutonium stock for commercial use is growing. It is clear that Mr. Mian’s criticism, though he mentioned no names, was targeting Japan, which has been amassing a large stockpile of plutonium for no apparent purpose.

Among the non-nuclear powers, reprocessing spent fuel to extract plutonium is permitted only in Japan. The time limit for this, stipulated in the current Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy, is 2018. Japan, where the nuclear fuel cycle policy is still uncertain, could be forced to “withdraw” due to outside pressure.

At a session of the Liberal Democratic Party held in late February, Taro Kono, a member of the Lower House, said to an official of the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, “You should speak sincerely with Aomori Prefecture and tell them that the nation’s policy may change.” Mr. Kono believes that “The cycle has failed, but it never stops. All the government can do is apologize for the errors and start reviewing Japan’s nuclear energy policy from scratch.”

Mr. Kono was told by an executive of an electric power company, which shuns heavy expenses, “Be assured that the plant in Rokkasho will not operate for the time being.” After the nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, Richard Armitage, the former U.S. deputy secretary of state, told Mr. Kono that he wants to see a halt to reprocessing in Japan.

The United States is concerned that some nations, such as South Korea and South Africa, will seek the right to engage in reprocessing, following Japan’s example. Mr. Kono said, “Japan should stop its reprocessing efforts and insist that other countries not get involved in reprocessing.” He laments the fact that, under current circumstances, the A-bombed nation could be paving the way for nuclear proliferation.

The international community holds deep doubts over Japan. The United States has pledged to protect Japan, its ally, with the U.S. nuclear umbrella, thinking that, otherwise, Japan might seek to build its own nuclear arsenal to rival China and North Korea. But, in fact, unless Japan should quit the NPT, this is an unrealistic concern. Still, it is undeniable that holding a large amount of plutonium stocks and repeated remarks by some conservative politicians that Japan should become a “nuclear-armed-nation” cast a shadow over Japan’s reputation.

How will Japan manage its surplus plutonium? This has become a major concern which severely tests the management skills of those in charge. And yet a private-sector corporation, financed by the electric power companies, is operating the whole business of the nuclear fuel cycle. Even among proponents of the nuclear fuel cycle, there are strong calls for the Japanese government to assume full responsibility for the nation’s surplus plutonium.

Saburo Kikuchi, director of the Radwaste and Decommissioning Center, said, “The cycle should be nationalized.” He has been the Japanese delegate to an international meeting on reprocessing and was even dubbed “Mr. Plutonium.”

Mr. Kikuchi headed the classified project where plutonium returned from France was carried to Japan by ship. The direction from the U.S. military instructed Japan to submerge the ship in the sea if it came under attack. Mr. Kikuchi, who had the final authority, keenly felt the weight of his responsibility, as if the ship was carrying an atomic bomb.

Drawn by a fait accompli, Japan is seeking to become deeply involved in the nuclear fuel cycle. If its sense of responsibility and initiative as a nation lacks strength, Japan will have no persuasive power to insist on non-proliferation or the prevention of nuclear terrorism.

Keywords

Plutonium

An element that rarely exists in nature, plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,000 years. When a uranium fuel rod is burned in a nuclear reactor, uranium-238, which is an element in uranium fuel and does not fission, absorbs neutrons and the new element “plutonium” is produced. Plutonium can be extracted by reprocessing spent nuclear fuel and become material for nuclear weapons or fast breeder reactors. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) states that eight kilograms of plutonium is needed to manufacture a nuclear weapon, though some experts believe that a lesser amount is sufficient.

Nuclear fuel cycle

A system in which spent nuclear fuel from nuclear power plants is reprocessed and the extracted uranium and plutonium are combined to form mixed oxide (MOX) fuel for reuse. A core fast-breeder reactor is called a “dream reactor” because it produces more plutonium than it consumes in fuel. However, the prototype fast-breeder reactor Monju has experienced a series of setbacks, and the Nuclear Regulation Authority issued an order to effectively halt the operation of Monju in May 2013. Problems include economic efficiency and safety concerns involving pluthermal (plutonium-thermal) power generation, where MOX fuel is burned at standard nuclear power plants.

Japan-U.S. Atomic Agreement

In line with this agreement, which Japan made with the United States in 1955, Japan was provided with enriched uranium and nuclear energy development then proceeded at full swing. A revised agreement in 1968 advanced the launch of commercial nuclear power plants. Under the agreement, U.S. consent is required to reprocess spent nuclear fuel, extract plutonium, and implement the nuclear fuel cycle policy. In the wake of India’s nuclear test in 1974, the United States strengthened its policy regarding the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, but agreed to Japan’s commercial reprocessing based on the existing Japan-U.S. Atomic Agreement. The next negotiations for revision of the agreement are due to conclude in 2018.

■Major incidents and influences on Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle policy

December 1953: U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower proclaims the idea of “Atoms for Peace” at the United Nations.

November 1955: Japan and the U.S. sign the Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy, an agreement that is central to providing Japan with enriched uranium.

July 1966: The Tokai nuclear power plant begins operations, marking Japan’s first use of commercial nuclear energy.

February 1970: Japan signs the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

June 1971: Construction of a reprocessing facility begins in Tokaimura in Ibaraki Prefecture.

May 1974: India conducts its first nuclear test.

April 1977: The U.S. announces a change in its nuclear non-proliferation policy, which includes indefinitely postponing commercial reprocessing in the country.

January 1981: The reprocessing facility in Tokaimura begins full-scale operations.

November 1984: A Japanese ship, the Seishin-maru, arrives back at port in Japan with 280 kilograms of plutonium returned from France.

April 1985: The governor of Aomori Prefecture accepts hosting facilities for the nuclear fuel cycle in the village of Rokkasho.

April 1986: A severe accident occurs at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

November 1987: Japan and the U.S. sign the current Agreement for Cooperation between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy. (It takes effect in July 1988.)

January 1993: A Japanese ship, the Akatsuki-maru, returns from France, arriving back at port in Japan with about 1.7 tons of plutonium.

January 1994: The U.K reprocessing plant THORP begins operations.

December 1995: The fast-breeder reactor Monju suffers a sodium-leak accident.

February 1997: The government approves “pluthermal,” or plutonium-thermal, power generation at Cabinet meetings.

February 1998: The French government officially decides to decommission the fast-breeder reactor Superphénix.

March 2006: The reprocessing plant in Rokkasho begins active tests to extract plutonium.

December 2009: The Genkai Nuclear Power Unit No. 3 of the Kyushu Electric Power Company is the first to introduce full-scale pluthermal.

March 2014: At the Nuclear Security Summit held in the Netherlands, a statement which calls for reductions in stockpiles of nuclear materials is adopted. Japan announces that about 300 kilograms of plutonium will be returned to the U.S.

March 2016: The reprocessing plant in Rokkasho is scheduled to begin operations.

(Originally published on March 28, 2015)