Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: The “Wall of Myth” in the U.S.

May 28, 2015

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

In 1995, a special exhibition of the fuselage of the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was planned at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. The exhibition also intended to display materials related to the atomic bombings. But the plan provoked a heated backlash in the United States. The “myth” which justifies the A-bomb attacks often intrudes when attempts are made to convey the inhumane consequences of the bombings and call for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Twenty years have passed since this controversy involving the Smithsonian exhibition. This article explores the “wall of myth” which still stands in the country that used the atomic bombs.

The hanger is crammed with aircraft, from space shuttles to Japanese kamikaze planes. The silver fuselage of Enola Gay stands out among them. In the bottom right corner of the panel which provides explanation, the size of the plane is described. Wingspan: 43 meters; Length: 30.2 meters: Height: 9 meters; and other measurements.

But there are no figures which indicate how many people became victims of the Hiroshima bombing. The only explanation given about what happened on August 6, 1945 is that this plane dropped the first atomic weapon used in warfare on Hiroshima, Japan.

This annex of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum is located about 40 kilometers west of downtown Washington D.C., the U.S. capital. The museum attracts about 1.3 million visitors annually, roughly the same number of people who visit Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Nicholas Partridge, 34, a public relations specialist, said there is no plan to add further explanation about Enola Gay. Mr. Partridge’s polite manner in guiding this reporter from Hiroshima seemed to stem from some nervousness.

When World War II ended, the airplane was dismantled and preserved. After being restored, part of its fuselage was displayed at the museum’s main building in downtown Washington, D.C. in 1995. When the annex opened in 2003, the whole plane was put on permanent display there.

In 1995, 50 years after the atomic bombings, the museum planned to display materials linked to the bombings, borrowed from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with photos showing the devastation in the aftermath of the attacks. But the planned exhibition was aborted after widespread opposition from veterans and conservative leaders.

A-bomb survivors have continued to pay visits to the museum and have spoken out against the exhibits which provide no information about the damage wrought by the bombings. But nothing has changed.

◆ ◆ ◆

The Los Alamos National Laboratory, located in New Mexico in the western part of the United States, served as the base for the development of the atomic bombs. At a museum affiliated with the laboratory, black-and-white photos of scientists are on display. This quickly makes it clear that the development of the atomic bombs is seen as an achievement of advanced technology that should be a source of pride.

Don Cavness, 68, who works at the museum, said in a gentle voice, with a friendly smile, that he would not have been born if the atomic bombs were not used.

In the closing days of World War II, Mr. Cavness’s father was scheduled to serve in Japan after returning from the front in Europe. His father and his mother, still boyfriend and girlfriend at the time, sat at a soda fountain and vowed to marry if he came home alive. Then they heard news of Japan’s surrender over the radio. The following year, Mr. Cavness said, he was born.

There are many Americans who share these same feelings, and they have left messages in notebooks for visitors to the museum: “My grandfather didn’t have to fight in Japan. Thank God.” “The atomic bombs ended the war more quickly and saved the lives of many Japanese people, too.”

The administration of President Harry S. Truman estimated that the number of casualties would be 500,000 or one million if the United States invaded Japan. The “myth” goes that the atomic bombs brought about Japan’s prompt surrender and saved more lives than were lost in the atomic bombings.

However, historians have pointed to official documents and testimonies by high-level figures which contradict this belief. The invasion of Japan was planned for November 1945, not as swiftly as many American citizens have come to believe since the war ended. In addition, the numbers of casualties had no solid basis: they were only estimates made by President Truman and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson after the war was over.

Still, there are many who hold fast to this myth. It is as if they can downplay the ethical dilemma of the atomic bombings by imagining that the number of people who “would have died” were larger.

In the eastern state of Massachusetts, I interviewed a 61-year-old relative of an American soldier who lost his life in the fighting against Japan. He spoke candidly in saying, “When the atomic bombs become the subject of conversation, people tread cautiously so they won’t enter a debate over the pros and cons of the atomic bombings. Some veterans and family members of war victims have begun to question, at the back of their minds, whether the bombings were really right or not.”

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the United States, the mood of celebration over the 70th anniversary of victory in World War II will prevail. In terms of historical perception, this is the gulf between the two nations, not simply the difference in perception involving the atomic bombings.

◆ ◆ ◆

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Martin Harwit, who was director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum when the exhibition featuring Enola Gay was being planned, and Hiroshi Harada, then director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum who had been negotiating with Mr. Harwit to lend materials involving the atomic bombing.

Why do you think the initial plan for the exhibition was met with such strong opposition?

I think the veterans felt that, because they had lived through these events, they wanted to tell the story of World War II. They felt that they were the only ones who could present a complete picture, that they understood the situation much better than historians or people at a museum who were reading documents and the diaries of leaders of that time.

The great number of letters protesting the exhibition show that the brunt of the criticism was directed your way.

Meanwhile, we were still trying to organize the event. We were planning to display not just the fuselage but also the latest research findings on the historical background of the war. We wanted to create an exhibition that was informative, accurate, and also respected the points of view of both Americans and the Japanese in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Giving adequate regard to both sides must have been a challenge.

For the purpose of the exhibition, the artifacts were essential. It must have been very difficult for the survivors to lend us items that had belonged to victims of the bombings and are imbued with deep emotions. I understand why it took time for the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to decide whether to lend these artifacts.

But as opposition from U.S. veterans grew stronger, I began to have the distinct impression that the survivors would no longer offer their cooperation and we wouldn’t be able to borrow the items we had asked for.

Now that 20 years have passed, do you think it would be possible to hold the exhibition as originally planned?

Last year was the 100th anniversary of World War I. Europe has been integrated and relations between former enemy countries have changed. But the Armenians and Turks have never settled their differences over the involvement of the Imperial Government in many Armenian deaths [in the genocide of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire]. They still view this history very differently.

Once a historical event becomes part of a nation’s identity or history, people hold fast to that view, and not just those who were involved in the event but also the children who want to honor what their grandparents and parents endured. A change of generation doesn’t necessarily bring change to the situation. But I haven’t studied current conditions between the U.S. and Japan, so I can’t really answer this question.

Last year you gave the documents you had copied shortly before you resigned as director of the museum and then held to the Smithsonian Institution Archives. Why?

Among the regents of the Smithsonian, there were some Congressmen who had been adamantly opposed to the exhibition and had also removed items from other exhibits at the museum that they didn’t want the public to see. I was worried that the items I would give might also be destroyed. So I had to make sure that wouldn’t happen through the help of former colleagues at the Smithsonian.

It’s important for scholars to study the issues that caused this controversy. I felt that I could provide some additional background that would be useful to them.

You hold in high esteem those who make a sincere effort to view history from various angles. It seems to me that your approach toward history is also quite sincere.

I felt that I could provide some additional background which would be useful to scholars. It was an important attempt to help address a controversy which is critical in the mind of the public. So I thought that the more information, the better it would be. It would be quite interesting to include the comments made by veterans’ organizations in these materials.

Profile

Martin Harwit

Born in The Czech Republic in 1931 (then Czechoslovakia), he was forced to flee the country when Germany invaded. Via Turkey, he moved to the United States then earned a doctorate in space physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After serving as head of the astrophysics section at Cornell University, he became a professor emeritus. From 1987 to 1995, he was director of the National Air and Space Museum. He is currently involved in projects at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the European Space Agency.

Can you describe your first contact with the National Air and Space Museum (NASM)?

In April 1993, shortly after I became director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Martin Harwit visited Hiroshima for the first time and spoke with Takashi Hiraoka, the mayor back then. They discussed the idea of lending materials from the museum for the exhibition at the Smithsonian.

It was a request from a world-class museum, and it would have offered us an important opportunity to convey the devastation of the bombing and Hiroshima’s wish for nuclear abolition to people in the United States. Still, we weren’t sure about the context in which the materials from our museum and the bomber would be displayed. It would be unacceptable if they were used in a way that ended up strengthening approval of the atomic bombings.

You had to be very careful.

The NASM was interested in borrowing photos and particular artifacts, including the charred lunch box, but these are very important personal belongings donated by the victims’ families. As a premise of discussing whether or not to lend these materials for the exhibition, the feelings of the victims had to be understood. I sincerely hoped that the NASM staff would come to Hiroshima on the anniversary of the atomic bombing. That day is very different from other days, and I believed they would feel something special. So, at my own discretion, I requested that he return on August 6. Mr. Harwit paid another visit to Hiroshima on that day, with members of his family.

We went to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound and attended the Peace Memorial Ceremony. He remained silent, but I felt his facial expressions conveyed his thoughts toward the victims. I thought he understood Hiroshima’s wishes. The mayor would make the final decision, but I believed we could lend the materials to him.

What did you think when the planned exhibition was canceled?

When the City of Hiroshima decided to loan the materials with conditions in November 1993, we knew that pressure on the NASM was growing.

We waited to receive the initial script for the exhibition. When we saw it, we realized that the plan had evolved into something very far from the wishes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I wanted to meet Mr. Harwit and ask him directly what they would do with the materials they had wanted to borrow, but he was forced into a very difficult position.

The positive view of the atomic bombings is a large obstacle not only in the United States but in other places as well.

After the exhibition was canceled, Mayor Hiraoka and I went to an A-bomb exhibition held at American University in July 1995. In a session for debate, many participants of Asian descent made critical remarks, like “How many people did the Japanese kill during the war?” This is something we must take seriously, and this issue is reflected in the exhibits at our peace museum. On the other hand, it’s not just A-bomb survivors who should take responsibility for the events of the war. This is something everyone should consider.

How do you feel now, looking back at how things developed?

Seen from a different angle, I think it was an opportunity to shine a light on the myth that the atomic bombings saved many lives, which had long been believed by the American public.

How can we convey the wish of Hiroshima and Nagasaki when many people still maintain the view that the atomic bombings were justified? This question has lingered even 70 years later. There is no shortcut. Each and every survivor and citizen must exchange views and communicate their thoughts at every opportunity possible, without ever giving up.

Profile

Hiroshi Harada

Born in Minami Ward, Hiroshima in 1939, he was 6 and at Hiroshima Station, about two kilometers from the hypocenter, when the atomic bomb exploded. After graduating from Waseda University, he became a Hiroshima city official in 1963. He was director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum from April 1993 to March 1997 and also served in such posts as board chairman of the Hiroshima City Culture Foundation. Currently, he gives talks on peace administration and his own A-bomb account.

When Martin Harwit visited Hiroshima in April 1993, he said that artifacts of the atomic bombing were essential so that Hiroshima’s suffering could be understood. As the director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, he requested that the City of Hiroshima lend materials from the Peace Memorial Museum. In November of that year, the city government stipulated conditions for providing these materials. One condition was that the exhibition explain the cruelty of nuclear weapons and contribute to their elimination.

Since the fuselage of Enola Gay was set to be displayed, it was only right that the exhibition help the American people understand what really happened beneath the mushroom cloud through artifacts, A-bomb accounts, historical documents, and other possible means. Both sides must have agreed that the exhibition should be balanced in this way.

But outside the planned exhibition, there was a very different opinion among the American public. This is seen clearly in the wording used in the signature drive by angry veterans, which argued that Enola Gay should be displayed “in a patriotic manner to instill pride in the viewer for the outstanding accomplishments of the United States.”

People felt that if the horror of the atomic bombings was conveyed through these artifacts from Hiroshima, it would undermine Enola Gay’s noble mission. Exhibits and methods that were incompatible with the idea that the atomic bombings were necessary came under attack. Under pressure, museum staff were forced to repeatedly revise their script for the exhibition. A charred lunch box from Hiroshima and a melted rosary from Nagasaki were removed from the list of exhibits, though the NASM had initially requested to borrow them. The title of the exhibition was altered because it linked the atomic bombs to the postwar nuclear age. The whole process perplexed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

According to Burton Bernstein, 78, professor emeritus at Stanford University, the media bear heavy responsibility for being swayed by the skillful manipulations of information by the Air Force Association and for controlling public opinion. He noted that the media reported that the artifacts at issue were still part of the exhibition plan, though they had actually been removed by the NASM at an earlier stage. Professor Bernstein, a leading expert on the history of World War II, served as an adviser to the special exhibition. He expressed anger as he recounted these events, as if they had taken place only recently.

In his book, Mr. Harwit wrote that he gave up hope for holding the exhibition at the moment he learned about a document discovered by Professor Bernstein.

The document implies that President Truman and U.S. military chiefs had estimated that the number of American casualties would not exceed 63,000 if mainland Japan was invaded without the use of an atomic bomb. After seeing this information, Mr. Harwit decided to change the figure of 250,000 casualties, which would have been included on an exhibition panel.

The level of opposition then reached the breaking point. Mr. Harwit’s desire to incorporate as many findings from historical research and authentic materials as possible was thwarted by a wave of “pride and patriotism.”

The initial script for the exhibition contained elements that would have elicited objections from the A-bombed cities. For the U.S. side, the contents are hardly radical. As the exhibition was being organized by the Air and Space Museum, the exhibition would have given ample explanations about the plane’s technology. It also provided vivid descriptions of how the crew members were engaged in their missions. On controversial matters, it offered a variety of documents and testimonies so that visitors could consider such issues for themselves.

The budget of the NASM is controlled by Congress. The museum’s main building is close to Capitol Hill, where politicians and lobbyists gather. “There was a limit,” said Professor Bernstein. “Can Japanese museums handle issues that cause controversy in your country? In order to engage in dialogues about history, we need to look at the whole picture of the war, not just the damage one country suffered.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Efforts to consider the atomic bombings from different viewpoints, and to gain deeper understanding of these events, have been made at George Mason University, a state university in Virginia. Professor Martin Sherwin, 77, is well known for his historical studies involving the atomic bombings.

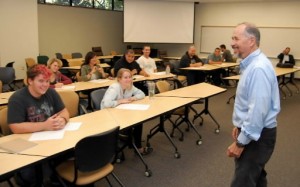

Professor Sherwin teaches a course which looks at the Cold War through visual imagery, with students learning about this history through lectures and films. Twenty students attend this course weekly, and they have already studied the history of the atomic bombings. The students responded to my questions during a class.

“The only thing we learned in high school was that the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and that was the end of World War II,” the students said. At their university, they learned that one of the purposes of the Truman government, in using the atomic bombs, was to demonstrate U.S. military might to the Soviet Union. They said they have also learned about the devastation caused by the atomic bombs and the reconstruction of the cities.

Patrick Woolverton, 29, a junior, said, “You need to have historical knowledge to be able to explain why the atomic bombings were a bad decision. We’re studying the history by looking at original sources, without simplifying things, and are coming to a deeper understanding.”

Unable to criticize grandparents’ generation

Emily Martin, 22, a senior, said she has begun to question the general view that the atomic bombings were necessary to end the war. Asked if she can share her opinion with older generations, she shook her head. “I heard my grandmother was involved in the Manhattan Project,” she said. “I’m learning to look at this history from an objective perspective, but I still can’t criticize the ‘family history’ that my grandparents believe in.”

Professor Sherwin hopes that such learning by younger American generations will hold the power to alter perceptions in the United States. But arguments over the atomic bombings will never end, he said with certainty. “Taking a negative view of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is incompatible with ‘American exceptionalism,’ the belief that the United States is the most wonderful country in the world,” he explained. “There will always be efforts to justify the bombings, even by disregarding the historical facts.”

Dialogue at grassroots level

Though findings from studies of the history have been reported, the American public is largely unfamiliar with this information. “People tend to turn away from, or turn a deaf ear to, things that are inconvenient. I want to approach the younger generations, in particular, who haven’t shown an interest in the atomic bombings, or don’t know about the consequences of these events,” said Professor Peter Kuznick, 64, as he greeted me in an office of the faculty of history at American University.

In cooperation with film director Oliver Stone, Professor Kuznick wrote the book Untold History of the United States, which also roused the interest of people in Japan. The book seeks to sway the general public to fundamentally review the historical myths believed in the United States, including the use of the atomic bombs.

In the same year that the exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum was canceled, an A-bomb exhibition was held at American University. Materials from Hiroshima and Nagasaki were put on display, and evoked a powerful response. Twenty years later, there is a plan to hold an exhibit of The Hiroshima Panels, a series of six paintings by the late Iri and Toshi Maruki which depict the atomic bombings, for the first time in the U.S. capital this year. At around the same time, the Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibition will take place, sponsored by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Professor Kuznick is involved in preparations for both exhibitions. He wants the American people to face the cruel devastation brought about by the atomic bombings and learn about the A-bomb survivors’ efforts to abolish nuclear weapons and create a peaceful world. He stresses the importance of facing this history together through grassroots dialogue.

◆ ◆ ◆

When America was embroiled in controversy over the idea of displaying materials linked to the atomic bombings, children in the state of New Mexico were caught in this same storm. The bronze statue at the center of the dispute is now on the grounds of the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum in the same state, welcoming visitors.

The Children’s Peace Statue was completed in August 1995, 50 years after the atomic bombings. The globe-shaped monument is 2.5 meters in diameter and is adorned with the images of animals and plants made by 3,000 children in 100 countries. The statue depicts the earth at peace, where all living things coexist in harmony without the threat of war.

The monument was the fruit of a campaign by local students, from elementary school to high school. Camy Condon, 76, who had lived in Japan for 10 years, performed a puppet play based on the late Eleanor Coerr’s book, Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, and this served to inspire the effort to create the monument. After learning about Sadako Sasaki, who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima but died of A-bomb-induced leukemia at the age of 12, and the movement to raise the Children’s Peace Monument, which now stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the children in New Mexico felt moved to act.

One-dollar fundraising campaign

The action taken by these students made an impact both inside and outside the United States. When they undertook a one-dollar donation campaign to raise money for the monument, 90,000 people in 63 countries, including people in Hiroshima, made contributions. The children also provided input for the design of the statue. Ms. Condon said, “We learned a lot from the children as they shared their ideas and acted independently.”

The problem they faced was where to put the statue. The first plan involved placing the monument in Los Alamos, the U.S. base for developing the atomic bombs and nuclear weapons.

But the local assembly in Los Alamos refused to accept the Children’s Peace Statue, arguing that the statue was not suitable for this site. At that point, the monument had no home. The Albuquerque Museum offered to host the statue, but then a group of war veterans demanded that the statue be removed. “People complained about unveiling the statue on the anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, so a variety of organizations held a ceremony each day for the whole month of August,” said Ms. Condon with a chuckle.

Statue relocated four times

The situation remains precarious. In August 2013, the statue was moved for the fourth time. Marilee Nason, 58, who oversaw placing it at the Albuquerque Museum, made efforts to bring it to the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum, where she now works as a curator.

The museum is known as a gathering place of hot-air balloon lovers from around the United States. Some of the museum’s main exhibits are balloon bombs, which were released by Japan and floated to the U.S. mainland during the war. Paintings by Reiko Okada, 85, a former art teacher who lives in Mihara, Hiroshima Prefecture, are on display in an exhibition hall. Ms. Okada depicts her experiences helping with the production of balloon bombs at a factory on Ohkunoshima Island, where she worked as a mobilized student.

Balloons and the Children’s Peace Statue may not seem to be closely connected. But Ms. Nason said, “Children can be at the mercy of war or they can help create a peaceful future. On this point, everyone will agree.”

Ms. Condon would be happy if the statue is accepted and loved there. At the same time, she hopes that one day Los Alamos will gladly give it a home.

Keywords

Enola Gay

Enola Gay is the name of the U.S. bomber that dropped the atomic bomb, dubbed “Little Boy,” on the city of Hiroshima. With two other planes, one to make scientific observations and the other to take photographs, Enola Gay took off from the island of Tinian, a U.S. dominion, on August 6, 1945. The plane was reportedly named after the mother of the pilot, Captain Paul Tibbets. Three days later, another bomber, Bockscar, dropped the second atomic bomb, called “Fat Man,” on Nagasaki. Bockscar is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio.

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an academic organization based in Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. It was established in 1846 in line with the wishes of the late British scientist James Smithson to expand human knowledge. It consists of 19 museums, including the National Museum of Natural History, the National Zoo, and research centers, making it the largest group of museums in the world. The main building of the National Air and Space Museum is in Washington, D.C. and it has an annex in the state of Virginia.

American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the idea that the United States is qualitatively different from other nations in its values and behaviors. Originating in the philosophy of the nation’s founding, it is based on pride in the belief that the country has exemplified liberty, rights, egalitarianism, and democracy. The term is also used when describing how the United States justifies its unilateralism in the world.

◆ ◆ ◆

Chronology of the related events

August 1945: Enola Gay drops an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

July 1949: The Air Force donates Enola Gay to the Smithsonian Institution. Enola Gay is later dismantled and preserved.

July 1976: The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM) opens in Washington D.C., the capital.

1980: Veterans of World War II call for restoring and preserving Enola Gay.

1985: The NASM begins to restore the fuselage of Enola Gay.

August 1987: Martin Harwit becomes director of the NASM.

July 1992: War veterans begin to demand that Enola Gay be displayed in a proud manner.

December 1992: An official decision is made to display Enola Gay.

April 1993: Director Martin Harwit and other members of the NASM visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki and request materials related to the atomic bombings be lent to the museum.

August 1993: Martin Harwit attends the Peace Memorial Ceremony in Hiroshima. War veterans pursue a signature drive, demanding that Enola Gay be displayed in a proud and patriotic manner.

October 1993: The NASM submits a list of artifacts they hope to borrow. The list includes 12 items from Hiroshima such as a charred lunch box and a watch that stopped at 8:15, the time of the atomic bombing.

November 1993: The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki decide to lend materials under six conditions. One condition is that the materials must be used to help advance the abolition of nuclear weapons.

January 1994: The first exhibition script is completed: “The Crossroads: The End of World War II, The Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War.”

April 1994: The Air Force Association discloses the contents of the exhibition and an article critical of this plan appears in its magazine.

May 1994: Experts of military history recommend to the NASM that the number of photos of child survivors be decreased while exhibits on Japan’s aggression in Asia be increased.

The second version of the exhibition script alters the title to “The Last Act: The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II.”

August 1994: Twenty-four members of the House of Representatives complain that the planned exhibition portrays Japan "more as an innocent victim than a ruthless aggressor" in World War II. They demand that the contents of the exhibition be changed.

September 1994: The Smithsonian Institution and groups of war veterans reach an agreement on drastic revisions to the exhibition script. The U.S. Senate adopts a resolution that the atomic bombings helped to bring World War II to a merciful end, which resulted in saving the lives of Americans and Japanese.

October 1994: The Executive Board of the Organization of American Historians approves a resolution criticizing the political intervention involving the Smithsonian Institution. A charred lunch box and four other items are removed from the list of exhibits in the fifth version of the exhibition script.

November 1994: Takakazu Kuriyama, the Japanese ambassador to the U.S., expresses his view that the Japanese government is in no position to make requests on the contents of the exhibition.

December 1994: The City of Hiroshima holds a meeting to listen to the views of intellectuals on lending A-bomb artifacts.

January 1995: Prompted by a document which said that the number of estimated casualties in the event of a U.S. invasion of Japan was 63,000, Martin Harwit, director of the NASM, modified the wording to appear on a display panel.

Groups of U.S. war veterans demand that the planned exhibition be canceled.

Eighty-one lawmakers demand that Director Harwit be dismissed.

The Smithsonian Institution Council decides the special exhibition should be canceled.

The White House press secretary states in a regular briefing that President Bill Clinton supports scaling back the exhibition.

April 1995: President Clinton states that the atomic bombings were justified and that the U.S. owed Japan no apology.

May 1995: Director Harwit resigns from office.

June 1995: Part of the fuselage is displayed without information on the damage caused by the bombing.

July 1995: An Atomic Bomb Exhibition is held at American University, which leads to Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibitions.

August 1995: Two hundred American historians send a letter of protest to the Smithsonian Institution.

December 2003: The fully restored fuselage of Enola Gay is put on permanent display in the annex of the NASM, a move which A-bomb survivors and historians protest.

April 2009: President Barack Obama delivers a speech in Prague, Czech Republic: “As the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act.”

(Originally published on February, 28, 2015)

In 1995, a special exhibition of the fuselage of the B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was planned at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. The exhibition also intended to display materials related to the atomic bombings. But the plan provoked a heated backlash in the United States. The “myth” which justifies the A-bomb attacks often intrudes when attempts are made to convey the inhumane consequences of the bombings and call for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Twenty years have passed since this controversy involving the Smithsonian exhibition. This article explores the “wall of myth” which still stands in the country that used the atomic bombs.

Number of victims left unstated

The hanger is crammed with aircraft, from space shuttles to Japanese kamikaze planes. The silver fuselage of Enola Gay stands out among them. In the bottom right corner of the panel which provides explanation, the size of the plane is described. Wingspan: 43 meters; Length: 30.2 meters: Height: 9 meters; and other measurements.

But there are no figures which indicate how many people became victims of the Hiroshima bombing. The only explanation given about what happened on August 6, 1945 is that this plane dropped the first atomic weapon used in warfare on Hiroshima, Japan.

This annex of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum is located about 40 kilometers west of downtown Washington D.C., the U.S. capital. The museum attracts about 1.3 million visitors annually, roughly the same number of people who visit Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Nicholas Partridge, 34, a public relations specialist, said there is no plan to add further explanation about Enola Gay. Mr. Partridge’s polite manner in guiding this reporter from Hiroshima seemed to stem from some nervousness.

When World War II ended, the airplane was dismantled and preserved. After being restored, part of its fuselage was displayed at the museum’s main building in downtown Washington, D.C. in 1995. When the annex opened in 2003, the whole plane was put on permanent display there.

In 1995, 50 years after the atomic bombings, the museum planned to display materials linked to the bombings, borrowed from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with photos showing the devastation in the aftermath of the attacks. But the planned exhibition was aborted after widespread opposition from veterans and conservative leaders.

A-bomb survivors have continued to pay visits to the museum and have spoken out against the exhibits which provide no information about the damage wrought by the bombings. But nothing has changed.

◆ ◆ ◆

The Los Alamos National Laboratory, located in New Mexico in the western part of the United States, served as the base for the development of the atomic bombs. At a museum affiliated with the laboratory, black-and-white photos of scientists are on display. This quickly makes it clear that the development of the atomic bombs is seen as an achievement of advanced technology that should be a source of pride.

Don Cavness, 68, who works at the museum, said in a gentle voice, with a friendly smile, that he would not have been born if the atomic bombs were not used.

In the closing days of World War II, Mr. Cavness’s father was scheduled to serve in Japan after returning from the front in Europe. His father and his mother, still boyfriend and girlfriend at the time, sat at a soda fountain and vowed to marry if he came home alive. Then they heard news of Japan’s surrender over the radio. The following year, Mr. Cavness said, he was born.

There are many Americans who share these same feelings, and they have left messages in notebooks for visitors to the museum: “My grandfather didn’t have to fight in Japan. Thank God.” “The atomic bombs ended the war more quickly and saved the lives of many Japanese people, too.”

Contradiction revealed

The administration of President Harry S. Truman estimated that the number of casualties would be 500,000 or one million if the United States invaded Japan. The “myth” goes that the atomic bombs brought about Japan’s prompt surrender and saved more lives than were lost in the atomic bombings.

However, historians have pointed to official documents and testimonies by high-level figures which contradict this belief. The invasion of Japan was planned for November 1945, not as swiftly as many American citizens have come to believe since the war ended. In addition, the numbers of casualties had no solid basis: they were only estimates made by President Truman and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson after the war was over.

Still, there are many who hold fast to this myth. It is as if they can downplay the ethical dilemma of the atomic bombings by imagining that the number of people who “would have died” were larger.

In the eastern state of Massachusetts, I interviewed a 61-year-old relative of an American soldier who lost his life in the fighting against Japan. He spoke candidly in saying, “When the atomic bombs become the subject of conversation, people tread cautiously so they won’t enter a debate over the pros and cons of the atomic bombings. Some veterans and family members of war victims have begun to question, at the back of their minds, whether the bombings were really right or not.”

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the United States, the mood of celebration over the 70th anniversary of victory in World War II will prevail. In terms of historical perception, this is the gulf between the two nations, not simply the difference in perception involving the atomic bombings.

◆ ◆ ◆

Excerpts of interviews with former directors of Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Martin Harwit, who was director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum when the exhibition featuring Enola Gay was being planned, and Hiroshi Harada, then director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum who had been negotiating with Mr. Harwit to lend materials involving the atomic bombing.

Martin Harwit sought to respect both points of view

Why do you think the initial plan for the exhibition was met with such strong opposition?

I think the veterans felt that, because they had lived through these events, they wanted to tell the story of World War II. They felt that they were the only ones who could present a complete picture, that they understood the situation much better than historians or people at a museum who were reading documents and the diaries of leaders of that time.

The great number of letters protesting the exhibition show that the brunt of the criticism was directed your way.

Meanwhile, we were still trying to organize the event. We were planning to display not just the fuselage but also the latest research findings on the historical background of the war. We wanted to create an exhibition that was informative, accurate, and also respected the points of view of both Americans and the Japanese in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Giving adequate regard to both sides must have been a challenge.

For the purpose of the exhibition, the artifacts were essential. It must have been very difficult for the survivors to lend us items that had belonged to victims of the bombings and are imbued with deep emotions. I understand why it took time for the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to decide whether to lend these artifacts.

But as opposition from U.S. veterans grew stronger, I began to have the distinct impression that the survivors would no longer offer their cooperation and we wouldn’t be able to borrow the items we had asked for.

Now that 20 years have passed, do you think it would be possible to hold the exhibition as originally planned?

Last year was the 100th anniversary of World War I. Europe has been integrated and relations between former enemy countries have changed. But the Armenians and Turks have never settled their differences over the involvement of the Imperial Government in many Armenian deaths [in the genocide of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire]. They still view this history very differently.

Once a historical event becomes part of a nation’s identity or history, people hold fast to that view, and not just those who were involved in the event but also the children who want to honor what their grandparents and parents endured. A change of generation doesn’t necessarily bring change to the situation. But I haven’t studied current conditions between the U.S. and Japan, so I can’t really answer this question.

Last year you gave the documents you had copied shortly before you resigned as director of the museum and then held to the Smithsonian Institution Archives. Why?

Among the regents of the Smithsonian, there were some Congressmen who had been adamantly opposed to the exhibition and had also removed items from other exhibits at the museum that they didn’t want the public to see. I was worried that the items I would give might also be destroyed. So I had to make sure that wouldn’t happen through the help of former colleagues at the Smithsonian.

It’s important for scholars to study the issues that caused this controversy. I felt that I could provide some additional background that would be useful to them.

You hold in high esteem those who make a sincere effort to view history from various angles. It seems to me that your approach toward history is also quite sincere.

I felt that I could provide some additional background which would be useful to scholars. It was an important attempt to help address a controversy which is critical in the mind of the public. So I thought that the more information, the better it would be. It would be quite interesting to include the comments made by veterans’ organizations in these materials.

Profile

Martin Harwit

Born in The Czech Republic in 1931 (then Czechoslovakia), he was forced to flee the country when Germany invaded. Via Turkey, he moved to the United States then earned a doctorate in space physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After serving as head of the astrophysics section at Cornell University, he became a professor emeritus. From 1987 to 1995, he was director of the National Air and Space Museum. He is currently involved in projects at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the European Space Agency.

Hiroshi Harada: No choice but to continue conveying the A-bomb reality

Can you describe your first contact with the National Air and Space Museum (NASM)?

In April 1993, shortly after I became director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Martin Harwit visited Hiroshima for the first time and spoke with Takashi Hiraoka, the mayor back then. They discussed the idea of lending materials from the museum for the exhibition at the Smithsonian.

It was a request from a world-class museum, and it would have offered us an important opportunity to convey the devastation of the bombing and Hiroshima’s wish for nuclear abolition to people in the United States. Still, we weren’t sure about the context in which the materials from our museum and the bomber would be displayed. It would be unacceptable if they were used in a way that ended up strengthening approval of the atomic bombings.

You had to be very careful.

The NASM was interested in borrowing photos and particular artifacts, including the charred lunch box, but these are very important personal belongings donated by the victims’ families. As a premise of discussing whether or not to lend these materials for the exhibition, the feelings of the victims had to be understood. I sincerely hoped that the NASM staff would come to Hiroshima on the anniversary of the atomic bombing. That day is very different from other days, and I believed they would feel something special. So, at my own discretion, I requested that he return on August 6. Mr. Harwit paid another visit to Hiroshima on that day, with members of his family.

We went to the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound and attended the Peace Memorial Ceremony. He remained silent, but I felt his facial expressions conveyed his thoughts toward the victims. I thought he understood Hiroshima’s wishes. The mayor would make the final decision, but I believed we could lend the materials to him.

What did you think when the planned exhibition was canceled?

When the City of Hiroshima decided to loan the materials with conditions in November 1993, we knew that pressure on the NASM was growing.

We waited to receive the initial script for the exhibition. When we saw it, we realized that the plan had evolved into something very far from the wishes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I wanted to meet Mr. Harwit and ask him directly what they would do with the materials they had wanted to borrow, but he was forced into a very difficult position.

The positive view of the atomic bombings is a large obstacle not only in the United States but in other places as well.

After the exhibition was canceled, Mayor Hiraoka and I went to an A-bomb exhibition held at American University in July 1995. In a session for debate, many participants of Asian descent made critical remarks, like “How many people did the Japanese kill during the war?” This is something we must take seriously, and this issue is reflected in the exhibits at our peace museum. On the other hand, it’s not just A-bomb survivors who should take responsibility for the events of the war. This is something everyone should consider.

How do you feel now, looking back at how things developed?

Seen from a different angle, I think it was an opportunity to shine a light on the myth that the atomic bombings saved many lives, which had long been believed by the American public.

How can we convey the wish of Hiroshima and Nagasaki when many people still maintain the view that the atomic bombings were justified? This question has lingered even 70 years later. There is no shortcut. Each and every survivor and citizen must exchange views and communicate their thoughts at every opportunity possible, without ever giving up.

Profile

Hiroshi Harada

Born in Minami Ward, Hiroshima in 1939, he was 6 and at Hiroshima Station, about two kilometers from the hypocenter, when the atomic bomb exploded. After graduating from Waseda University, he became a Hiroshima city official in 1963. He was director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum from April 1993 to March 1997 and also served in such posts as board chairman of the Hiroshima City Culture Foundation. Currently, he gives talks on peace administration and his own A-bomb account.

“Pride and patriotism” prevent exhibition of A-bomb materials

When Martin Harwit visited Hiroshima in April 1993, he said that artifacts of the atomic bombing were essential so that Hiroshima’s suffering could be understood. As the director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, he requested that the City of Hiroshima lend materials from the Peace Memorial Museum. In November of that year, the city government stipulated conditions for providing these materials. One condition was that the exhibition explain the cruelty of nuclear weapons and contribute to their elimination.

Since the fuselage of Enola Gay was set to be displayed, it was only right that the exhibition help the American people understand what really happened beneath the mushroom cloud through artifacts, A-bomb accounts, historical documents, and other possible means. Both sides must have agreed that the exhibition should be balanced in this way.

But outside the planned exhibition, there was a very different opinion among the American public. This is seen clearly in the wording used in the signature drive by angry veterans, which argued that Enola Gay should be displayed “in a patriotic manner to instill pride in the viewer for the outstanding accomplishments of the United States.”

People felt that if the horror of the atomic bombings was conveyed through these artifacts from Hiroshima, it would undermine Enola Gay’s noble mission. Exhibits and methods that were incompatible with the idea that the atomic bombings were necessary came under attack. Under pressure, museum staff were forced to repeatedly revise their script for the exhibition. A charred lunch box from Hiroshima and a melted rosary from Nagasaki were removed from the list of exhibits, though the NASM had initially requested to borrow them. The title of the exhibition was altered because it linked the atomic bombs to the postwar nuclear age. The whole process perplexed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

According to Burton Bernstein, 78, professor emeritus at Stanford University, the media bear heavy responsibility for being swayed by the skillful manipulations of information by the Air Force Association and for controlling public opinion. He noted that the media reported that the artifacts at issue were still part of the exhibition plan, though they had actually been removed by the NASM at an earlier stage. Professor Bernstein, a leading expert on the history of World War II, served as an adviser to the special exhibition. He expressed anger as he recounted these events, as if they had taken place only recently.

In his book, Mr. Harwit wrote that he gave up hope for holding the exhibition at the moment he learned about a document discovered by Professor Bernstein.

The document implies that President Truman and U.S. military chiefs had estimated that the number of American casualties would not exceed 63,000 if mainland Japan was invaded without the use of an atomic bomb. After seeing this information, Mr. Harwit decided to change the figure of 250,000 casualties, which would have been included on an exhibition panel.

The level of opposition then reached the breaking point. Mr. Harwit’s desire to incorporate as many findings from historical research and authentic materials as possible was thwarted by a wave of “pride and patriotism.”

The initial script for the exhibition contained elements that would have elicited objections from the A-bombed cities. For the U.S. side, the contents are hardly radical. As the exhibition was being organized by the Air and Space Museum, the exhibition would have given ample explanations about the plane’s technology. It also provided vivid descriptions of how the crew members were engaged in their missions. On controversial matters, it offered a variety of documents and testimonies so that visitors could consider such issues for themselves.

The budget of the NASM is controlled by Congress. The museum’s main building is close to Capitol Hill, where politicians and lobbyists gather. “There was a limit,” said Professor Bernstein. “Can Japanese museums handle issues that cause controversy in your country? In order to engage in dialogues about history, we need to look at the whole picture of the war, not just the damage one country suffered.”

◆ ◆ ◆

Young Americans consider atomic bombings from different viewpoints

Efforts to consider the atomic bombings from different viewpoints, and to gain deeper understanding of these events, have been made at George Mason University, a state university in Virginia. Professor Martin Sherwin, 77, is well known for his historical studies involving the atomic bombings.

Professor Sherwin teaches a course which looks at the Cold War through visual imagery, with students learning about this history through lectures and films. Twenty students attend this course weekly, and they have already studied the history of the atomic bombings. The students responded to my questions during a class.

“The only thing we learned in high school was that the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and that was the end of World War II,” the students said. At their university, they learned that one of the purposes of the Truman government, in using the atomic bombs, was to demonstrate U.S. military might to the Soviet Union. They said they have also learned about the devastation caused by the atomic bombs and the reconstruction of the cities.

Patrick Woolverton, 29, a junior, said, “You need to have historical knowledge to be able to explain why the atomic bombings were a bad decision. We’re studying the history by looking at original sources, without simplifying things, and are coming to a deeper understanding.”

Unable to criticize grandparents’ generation

Emily Martin, 22, a senior, said she has begun to question the general view that the atomic bombings were necessary to end the war. Asked if she can share her opinion with older generations, she shook her head. “I heard my grandmother was involved in the Manhattan Project,” she said. “I’m learning to look at this history from an objective perspective, but I still can’t criticize the ‘family history’ that my grandparents believe in.”

Professor Sherwin hopes that such learning by younger American generations will hold the power to alter perceptions in the United States. But arguments over the atomic bombings will never end, he said with certainty. “Taking a negative view of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is incompatible with ‘American exceptionalism,’ the belief that the United States is the most wonderful country in the world,” he explained. “There will always be efforts to justify the bombings, even by disregarding the historical facts.”

Dialogue at grassroots level

Though findings from studies of the history have been reported, the American public is largely unfamiliar with this information. “People tend to turn away from, or turn a deaf ear to, things that are inconvenient. I want to approach the younger generations, in particular, who haven’t shown an interest in the atomic bombings, or don’t know about the consequences of these events,” said Professor Peter Kuznick, 64, as he greeted me in an office of the faculty of history at American University.

In cooperation with film director Oliver Stone, Professor Kuznick wrote the book Untold History of the United States, which also roused the interest of people in Japan. The book seeks to sway the general public to fundamentally review the historical myths believed in the United States, including the use of the atomic bombs.

In the same year that the exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum was canceled, an A-bomb exhibition was held at American University. Materials from Hiroshima and Nagasaki were put on display, and evoked a powerful response. Twenty years later, there is a plan to hold an exhibit of The Hiroshima Panels, a series of six paintings by the late Iri and Toshi Maruki which depict the atomic bombings, for the first time in the U.S. capital this year. At around the same time, the Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibition will take place, sponsored by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Professor Kuznick is involved in preparations for both exhibitions. He wants the American people to face the cruel devastation brought about by the atomic bombings and learn about the A-bomb survivors’ efforts to abolish nuclear weapons and create a peaceful world. He stresses the importance of facing this history together through grassroots dialogue.

◆ ◆ ◆

American children campaign for Children’s Peace Statue

When America was embroiled in controversy over the idea of displaying materials linked to the atomic bombings, children in the state of New Mexico were caught in this same storm. The bronze statue at the center of the dispute is now on the grounds of the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum in the same state, welcoming visitors.

The Children’s Peace Statue was completed in August 1995, 50 years after the atomic bombings. The globe-shaped monument is 2.5 meters in diameter and is adorned with the images of animals and plants made by 3,000 children in 100 countries. The statue depicts the earth at peace, where all living things coexist in harmony without the threat of war.

The monument was the fruit of a campaign by local students, from elementary school to high school. Camy Condon, 76, who had lived in Japan for 10 years, performed a puppet play based on the late Eleanor Coerr’s book, Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, and this served to inspire the effort to create the monument. After learning about Sadako Sasaki, who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima but died of A-bomb-induced leukemia at the age of 12, and the movement to raise the Children’s Peace Monument, which now stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the children in New Mexico felt moved to act.

One-dollar fundraising campaign

The action taken by these students made an impact both inside and outside the United States. When they undertook a one-dollar donation campaign to raise money for the monument, 90,000 people in 63 countries, including people in Hiroshima, made contributions. The children also provided input for the design of the statue. Ms. Condon said, “We learned a lot from the children as they shared their ideas and acted independently.”

The problem they faced was where to put the statue. The first plan involved placing the monument in Los Alamos, the U.S. base for developing the atomic bombs and nuclear weapons.

But the local assembly in Los Alamos refused to accept the Children’s Peace Statue, arguing that the statue was not suitable for this site. At that point, the monument had no home. The Albuquerque Museum offered to host the statue, but then a group of war veterans demanded that the statue be removed. “People complained about unveiling the statue on the anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, so a variety of organizations held a ceremony each day for the whole month of August,” said Ms. Condon with a chuckle.

Statue relocated four times

The situation remains precarious. In August 2013, the statue was moved for the fourth time. Marilee Nason, 58, who oversaw placing it at the Albuquerque Museum, made efforts to bring it to the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum, where she now works as a curator.

The museum is known as a gathering place of hot-air balloon lovers from around the United States. Some of the museum’s main exhibits are balloon bombs, which were released by Japan and floated to the U.S. mainland during the war. Paintings by Reiko Okada, 85, a former art teacher who lives in Mihara, Hiroshima Prefecture, are on display in an exhibition hall. Ms. Okada depicts her experiences helping with the production of balloon bombs at a factory on Ohkunoshima Island, where she worked as a mobilized student.

Balloons and the Children’s Peace Statue may not seem to be closely connected. But Ms. Nason said, “Children can be at the mercy of war or they can help create a peaceful future. On this point, everyone will agree.”

Ms. Condon would be happy if the statue is accepted and loved there. At the same time, she hopes that one day Los Alamos will gladly give it a home.

Keywords

Enola Gay

Enola Gay is the name of the U.S. bomber that dropped the atomic bomb, dubbed “Little Boy,” on the city of Hiroshima. With two other planes, one to make scientific observations and the other to take photographs, Enola Gay took off from the island of Tinian, a U.S. dominion, on August 6, 1945. The plane was reportedly named after the mother of the pilot, Captain Paul Tibbets. Three days later, another bomber, Bockscar, dropped the second atomic bomb, called “Fat Man,” on Nagasaki. Bockscar is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Ohio.

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an academic organization based in Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. It was established in 1846 in line with the wishes of the late British scientist James Smithson to expand human knowledge. It consists of 19 museums, including the National Museum of Natural History, the National Zoo, and research centers, making it the largest group of museums in the world. The main building of the National Air and Space Museum is in Washington, D.C. and it has an annex in the state of Virginia.

American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the idea that the United States is qualitatively different from other nations in its values and behaviors. Originating in the philosophy of the nation’s founding, it is based on pride in the belief that the country has exemplified liberty, rights, egalitarianism, and democracy. The term is also used when describing how the United States justifies its unilateralism in the world.

◆ ◆ ◆

Chronology of the related events

August 1945: Enola Gay drops an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

July 1949: The Air Force donates Enola Gay to the Smithsonian Institution. Enola Gay is later dismantled and preserved.

July 1976: The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM) opens in Washington D.C., the capital.

1980: Veterans of World War II call for restoring and preserving Enola Gay.

1985: The NASM begins to restore the fuselage of Enola Gay.

August 1987: Martin Harwit becomes director of the NASM.

July 1992: War veterans begin to demand that Enola Gay be displayed in a proud manner.

December 1992: An official decision is made to display Enola Gay.

April 1993: Director Martin Harwit and other members of the NASM visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki and request materials related to the atomic bombings be lent to the museum.

August 1993: Martin Harwit attends the Peace Memorial Ceremony in Hiroshima. War veterans pursue a signature drive, demanding that Enola Gay be displayed in a proud and patriotic manner.

October 1993: The NASM submits a list of artifacts they hope to borrow. The list includes 12 items from Hiroshima such as a charred lunch box and a watch that stopped at 8:15, the time of the atomic bombing.

November 1993: The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki decide to lend materials under six conditions. One condition is that the materials must be used to help advance the abolition of nuclear weapons.

January 1994: The first exhibition script is completed: “The Crossroads: The End of World War II, The Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War.”

April 1994: The Air Force Association discloses the contents of the exhibition and an article critical of this plan appears in its magazine.

May 1994: Experts of military history recommend to the NASM that the number of photos of child survivors be decreased while exhibits on Japan’s aggression in Asia be increased.

The second version of the exhibition script alters the title to “The Last Act: The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II.”

August 1994: Twenty-four members of the House of Representatives complain that the planned exhibition portrays Japan "more as an innocent victim than a ruthless aggressor" in World War II. They demand that the contents of the exhibition be changed.

September 1994: The Smithsonian Institution and groups of war veterans reach an agreement on drastic revisions to the exhibition script. The U.S. Senate adopts a resolution that the atomic bombings helped to bring World War II to a merciful end, which resulted in saving the lives of Americans and Japanese.

October 1994: The Executive Board of the Organization of American Historians approves a resolution criticizing the political intervention involving the Smithsonian Institution. A charred lunch box and four other items are removed from the list of exhibits in the fifth version of the exhibition script.

November 1994: Takakazu Kuriyama, the Japanese ambassador to the U.S., expresses his view that the Japanese government is in no position to make requests on the contents of the exhibition.

December 1994: The City of Hiroshima holds a meeting to listen to the views of intellectuals on lending A-bomb artifacts.

January 1995: Prompted by a document which said that the number of estimated casualties in the event of a U.S. invasion of Japan was 63,000, Martin Harwit, director of the NASM, modified the wording to appear on a display panel.

Groups of U.S. war veterans demand that the planned exhibition be canceled.

Eighty-one lawmakers demand that Director Harwit be dismissed.

The Smithsonian Institution Council decides the special exhibition should be canceled.

The White House press secretary states in a regular briefing that President Bill Clinton supports scaling back the exhibition.

April 1995: President Clinton states that the atomic bombings were justified and that the U.S. owed Japan no apology.

May 1995: Director Harwit resigns from office.

June 1995: Part of the fuselage is displayed without information on the damage caused by the bombing.

July 1995: An Atomic Bomb Exhibition is held at American University, which leads to Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibitions.

August 1995: Two hundred American historians send a letter of protest to the Smithsonian Institution.

December 2003: The fully restored fuselage of Enola Gay is put on permanent display in the annex of the NASM, a move which A-bomb survivors and historians protest.

April 2009: President Barack Obama delivers a speech in Prague, Czech Republic: “As the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act.”

(Originally published on February, 28, 2015)