7. The Burden of Four Ounces of Cesium

Mar. 26, 2013

Chapter 6: Brazil and Namibia

Part 1: Cesium Contamination in Goiânia

Part 1: Cesium Contamination in Goiânia

We found it hard to believe that a mere four ounces of cesium-137 could have such horrific effects on the people of a city. We became interested in the fate of the vast amount of goods and material that were declared contaminated by radiation after the Goiania accident. By chance we met Weber Borges, a freelance journalist investigating the accident, who urged us to visit the storage site.

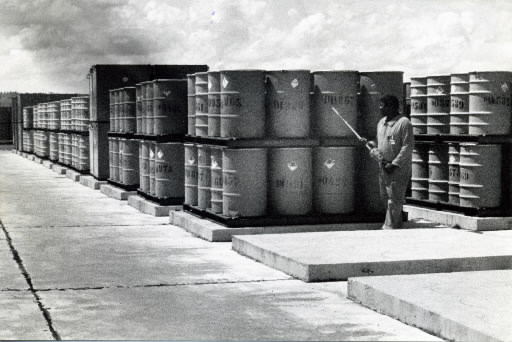

The site was located in some hills fourteen miles from the center of Goiânia. Through the barbed-wire fence we could see shipping containers and drums piled haphazardly on top of each other. The entrance was guarded by an armed soldier.

As we walked around the site, our guide, who was carrying a radiation detector, reeled off the numbers of waste containers. "There are 4,250 oil drums, 1,327 small containers, 12 large containers, and 8 large concrete-filled drums."

When the true nature of the cesium contamination came to light, the Brazilian government mobilized six hundred workers, including two hundred army personnel, to demolish houses in the affected areas. The pile of waste we could see was the result of three months of this decontamination activity. As we approached the concrete-filled drums, the needle on our guide's radiation detector reacted violently.

"This drum contains a dog that belonged to one of the men who took the cesium from the abandoned hospital. That row of drums over there contains the house of Leide Ferreira and all its contents, including a sixteen-inch layer of earth from underneath it. You want to know if it's safe? Of course it is; I've been working here for a year and a half now, with no problems at all."

That same night we met Borges at Dr. Curado's house, where he showed us a video he had taken of the contaminated houses being demolished on December 6, 1987. Water was being poured on the houses as they were knocked down.

"That's to prevent contamination spreading via dust," the journalist explained. "But as you can see, the water is just running off into the street; some scientists in São Paulo are starting to get worried about the possibility of secondary contamination from the water." In another film, we saw workers demolishing houses again; some were wearing protective gear reminiscent of spacesuits, but others were dressed in T-shirts.

"This is the kind of slapdash waste collection that was carried out for three months," Borges said angrily. Dr. Curado nodded in agreement. Borges was fired from his job at the local television station only a week after the accident.

"I happened to criticize the government's cleanup operation on the national news, so the next day I was fired—that's not uncommon here in Brazil." Since his dismissal Borges has continued to conduct his own investigation into the cesium tragedy.

The accident has left an indelible scar on the minds of the people of the peaceful provincial city of Goiânia, and as yet they cannot feel completely confident that further tragedies will not occur. Already four of the drums storing contaminated material from the accident have corroded, and their contents have been moved to other containers. Moreover, the present site is only temporary and will soon need to be vacated; another has yet to be decided on.

Borges commented, "Money buys technology, but it doesn't necessarily buy good management. The tragedy of Goiânia has proved this, but neither the doctors responsible for abandoning potentially dangerous equipment nor the government which was supposed to be supervising their activities have been questioned about their part in the accident. How can we believe that the same thing won't happen again?"