- A-bomb Images

- Record of Hiroshima: Photos of A-bomb Dome taken by Yuichiro Sasaki

Record of Hiroshima: Photos of A-bomb Dome taken by Yuichiro Sasaki

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

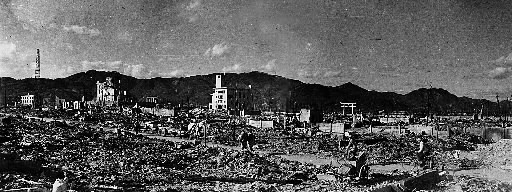

Silent grave markers denounce terrible devastation

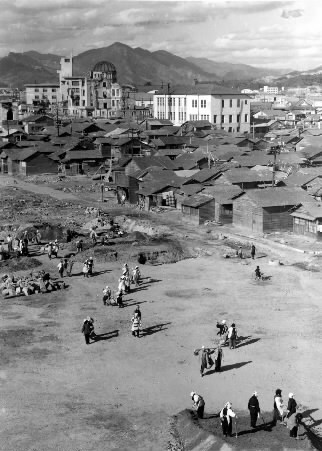

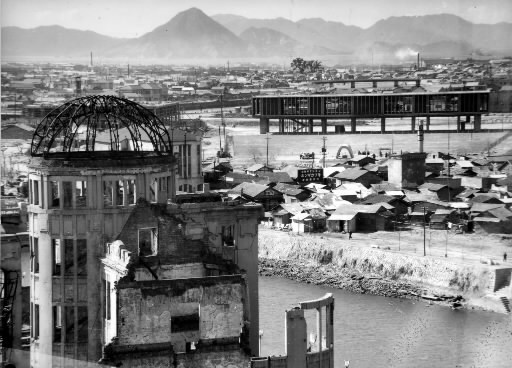

It has been learned that photographs taken by Yuichiro Sasaki (1917-1980) will be held in electronic archives and made available for online viewing. Through his work, Mr. Sasaki recorded Hiroshima’s devastation and recovery from the atomic bombing. At the request of the Chugoku Shimbun, Yugo Shioura, 58, the photographer’s son, agreed to allow Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum to compile a database of his father’s images. Mr. Sasaki, one of Hiroshima’s leading photographers of that era, began focusing his lens on the A-bomb Dome shortly after the bombing and went on to capture the dawn of the nuclear age. This article will look at the life of the man who witnessed this time through his viewfinder and gave testimony through his photographs of the city.

Doggedly photographed reconstruction and change

“He was tenacious,” Yugo said of his father. “Otherwise, he wouldn’t have been able to do this work.” Nearly every day, up to the last years of his life, Mr. Sasaki would bicycle around the city and take photos. His passion for photographing Hiroshima began when he returned to his hometown and found the city in ruins.

Yuichiro Sasaki was born in today’s Nishi Tokaichi district in downtown Hiroshima and studied photography at a photography school in Tokyo. During the war, he took photos for a weekly bulletin published by the Cabinet Information Board. After Japan’s defeat, he returned to Hiroshima on August 18, 1945. He carried with him some rolls of film, which were given to him as severance pay. He found that 13 members of his family had perished, including his mother, his brother and his brother’s family, and his sisters.

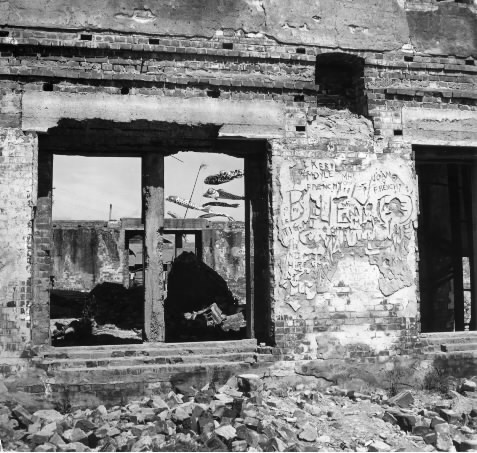

He once recalled, in an article that appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on August 3, 1968: “I was just going to take photos of the places where my relatives died...but then I wanted to take photos of another place, and then another. That’s how I went deeper and deeper into this.” He ended up taking photos of grave markers all over the Hiroshima delta.

In those days, the Chugoku Shimbun company, whose headquarters had been gutted by fire in the A-bomb blast, had difficulty obtaining camera film. Mr. Sasaki was able to get rolls of film, 100 feet long, by serving as a guide for photographers from overseas. While walking around the city with his camera, early in the morning, he was sometimes questioned by the police or stared at by others. Still, he continued capturing the evolving cityscape as it went through the process of post-war reconstruction. He made a base for his activities in the Motoujina part of Minami Ward, earning a living by taking pictures for tourists while persisting in his efforts to record Hiroshima in photographs.

Akira Matsuura, 73, a former city news reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun, was on friendly terms with Mr. Sasaki. Mr. Matsuura said he still recalls Mr. Sasaki’s words: “I took photos of gravestones of A-bomb victims, including my family’s plot. There weren’t any people in these pictures.” Through the viewfinder, he saw his lost relatives.

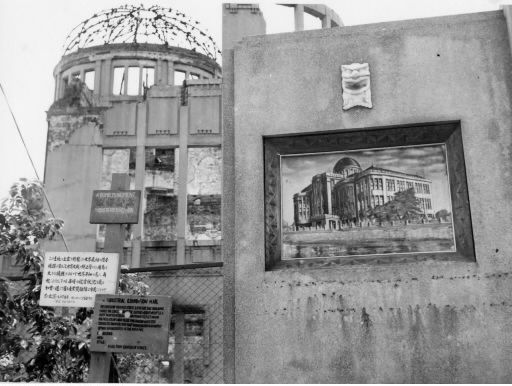

Aware of the suffering that was inflicted by the atomic bombing, he devoted himself to taking photos of silent gravestones, rather than images with aggressive anti-nuclear messages. This is why he went on taking photos of the A-bomb Dome. Mr. Matsuura introduced Mr. Sasaki to a documentary film director in Tokyo. With the help of this director, he held an exhibition of his work at Matsuya Department Store in Ginza, Tokyo in 1969, two years after the dome underwent a preservation project. The exhibition, titled “Hiroshima Diary,” was met by a strong response from the public.

In the brochure for the exhibition, Mr. Sasaki described his work in the ruins of the city: “I continued pressing the shutter, and before I knew it, I had taken 100,000 pictures. The negatives mean everything to me now.” Overcoming an eye disease, he remained an independent photographer, his words conveying pride in the way he chose to live his life.

The following year, Mr. Sasaki issued Hiroshima Since August 1945, published by the Asahi Shimbun. He later published a bilingual book titled Hiroshima Diary. He called for collecting and preserving photographs related to the atomic bombing, and the Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima was formed in 1978. The association gathered 278 pictures from 20 people. Mr. Sasaki resigned from the group, and died of liver failure in 1980 at the age of 63.

While copies of photos held by the association attracted attention when they were exhibited at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Mr. Sasaki’s photos were given special praise. His wife Kiyomi, 85, preserved his work carefully. However, when she lent out some photos, on request, they were captioned incorrectly and others were never returned to her.

After consulting with his mother, now hospitalized, Mr. Sasaki’s son Yugo sent the first 507 photos and 20 files of negatives, in chronological order, for inclusion in the electronic archive. He made this decision to realize his late father’s wish. “I took these photos in the hope that they will be living witnesses to what happened,” Mr. Sasaki once said.

Expression “domed building” appears in U.S. military newspaper in August 1946

Name “A-bomb Dome” comes into general use in 1952, after end of occupation

In 1990, the City of Hiroshima said that it is not clear who began using the name “A-bomb Dome” and when, and suggested that citizens spontaneously began using this term, something now often quoted by the media. But is this really the case? In researching this part of history, I learned how the structure became known as the “A-bomb Dome” to Japanese and Americans alike.

According to the latest research, the atomic bomb exploded at a height of 600 meters above the ground, 160 meters southeast of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, a three-story brick building.

The Osaka edition of the Mainichi Shimbun, dated September 13, 1945, published the first photo involving the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and reported that the roof of the hall had been blown off. The Chugoku Shimbun, still in the process of reconstruction after the bombing, ran its first photo of the damaged building on June 8, 1946 in an article about an event which involved sketching the war-ravaged area. That same year, on July 6, the Evening Edition Hiroshima, published by another company, reported that a tower was erected in the Nakajima Honmachi district to comfort the souls of the A-bomb dead and said that the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall on the opposite side of the river was now in ruins. This was around the time that the city decided to turn the area into a park.

But when was the word “dome” first used to describe it? Studying English-language newspapers at the National Diet Library, I found a photo of the shattered structure in the August 6, 1946 Pacific Edition of the Stars and Stripes, an American newspaper for the armed forces. “Bomb exploded 800 feet over domed building,” it said. On the front page of the August 5, 1947 issue, it was reported that “Officials recently decided to preserve this building as a memorial.” This assumption, though, may have been made based on the decision to preserve the area by constructing a park. At the time, the preservation of the building itself had not been resolved.

In a booklet titled Tour of Hiroshima, The Atomic City, published by U.S. and British occupation forces, an illustration appears with a caption that refers to the structure as a “domed building” and explains that “everything within a radius of two kilometers from the hypocenter was completely burned.” The booklet was donated to Peace Memorial Museum in 2005 by a family member of a late British veteran who had visited Hiroshima in 1946.

Meanwhile, Hiroshima, the well-known account of the atomic bombing by John Hersey that appeared in the August 31, 1946 issue of The New Yorker, as well as the September 15, 1947 issue of Life magazine, which covered the first Peace Festival held by the City of Hiroshima, refers to the building as the “Industrial Exhibition Hall,” an English equivalent of the Japanese name.

The first usage of the word “dome” by the Chugoku Shimbun occurred in the issue published on August 2, 1947. In connection to the upcoming peace festival, the article said that “the damaged dome stands as if calling to the sky for peace.”

The “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing,” selected by the city’s reconstruction division, did not include the former Industrial Promotion Hall in its list. It was included, though, in the list of “notable sites of the atomic bombing” that was proposed by an Australian serviceman who served as a consultant for the post-war reconstruction. As construction boomed, and the area around the hypocenter was transformed into a park, the rounded dome of the western-style building became a symbol of the atomic bombing.

In a Chugoku Shimbun article that appeared on August 7, 1949, which reported on the winner of the design competition for Peace Memorial Park, the dome was mentioned in describing the devastation of the atomic bombing. The article referred to it as “the dome of the former Industrial Promotion Hall, the wreckage of the atom.”

The expression “Atomic Bomb Dome” appeared in an editorial on June 23, 1950 on sites of interest in the city. However, after the Korean War broke out two days later, this term promptly disappeared. Was it because the expression ruffled the United States, which had declared the possible use of nuclear arms in this conflict?

In those days, such terms as “A-bomb orphans” and “A-bomb maidens” were used. Reflecting on these terms today, it must be said that they were thoughtless expressions, even though the word “A-bomb” was used to refer to the damage caused by the bomb.

A book of haiku titled Yoru (Night), published in September 1950, was found in the Peace Memorial Museum library. The book includes a haiku, or seventeen-syllable poem, titled “Kanatokogumo, Genbaku Dome ni, Arikuruu” (“Anvil cloud, at the A-bomb Dome, Ants Running Wild”) that was written by a high school teacher living in the city of Shobara in northern Hiroshima Prefecture. The teacher, named Fujii, entered Hiroshima shortly after the bombing and was exposed to the bomb’s radiation. (Mr. Fujii died in 2003.) His book was not included in the list of censored documents by the occupation forces, and it is believed to be the first time that the atomic bombing was described with the words “A-bomb Dome.”

Before the conclusion of the peace treaty between Japan and the United States, the Chugoku Shimbun of August 6, 1951, and Tokyo evening edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun of August 16 of the same year, carried aerial photos with captions referring to the structure as the “A-bomb Dome.” In August 1952, a book of photographs titled Genbaku Daiichigo, Hiroshima no shashin Kiroku (The First Atomic Bomb, Photographic Record of Hiroshima) was published by the Asahi Press. A double-page feature was titled “the miserable state of the ‘A-bomb Dome.’” An special edition of the magazine Kaizo (Reorganization), published that November, included a report headlined “A-bomb Dome” by Mitsuo Taketani, a nuclear physicist. (Mr. Taketani died in 2000.)

Finally, in 1952, after the occupation ended, the expression “A-bomb Dome” came into general use. In 1953, the City of Hiroshima used the term in a tourism map in a manual for city administrators. (Within the text, it was referred to as the former Industrial Promotion Hall.)

The New York Times of July 31, 1955, carried a feature article headlined “Hiroshima—Ten Years After.” “This wreck, formerly the stately Industrial Exhibition Hall, is preserved deliberately as a reminder and symbol. The stark hemisphere of burned twisted steel at its top suggested its new name ‘The Atomic Dome’.” This is when the name took hold both in Japan and the United States.

The A-bomb Dome has long served as a warning that the use of nuclear weapons can create terrible destruction. In 1996, it was added to UNESCO’s list of World Heritage sites as “Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome).”

(Originally published on June 5, 2007)

Silent grave markers denounce terrible devastation

It has been learned that photographs taken by Yuichiro Sasaki (1917-1980) will be held in electronic archives and made available for online viewing. Through his work, Mr. Sasaki recorded Hiroshima’s devastation and recovery from the atomic bombing. At the request of the Chugoku Shimbun, Yugo Shioura, 58, the photographer’s son, agreed to allow Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum to compile a database of his father’s images. Mr. Sasaki, one of Hiroshima’s leading photographers of that era, began focusing his lens on the A-bomb Dome shortly after the bombing and went on to capture the dawn of the nuclear age. This article will look at the life of the man who witnessed this time through his viewfinder and gave testimony through his photographs of the city.

Doggedly photographed reconstruction and change

“He was tenacious,” Yugo said of his father. “Otherwise, he wouldn’t have been able to do this work.” Nearly every day, up to the last years of his life, Mr. Sasaki would bicycle around the city and take photos. His passion for photographing Hiroshima began when he returned to his hometown and found the city in ruins.

Yuichiro Sasaki was born in today’s Nishi Tokaichi district in downtown Hiroshima and studied photography at a photography school in Tokyo. During the war, he took photos for a weekly bulletin published by the Cabinet Information Board. After Japan’s defeat, he returned to Hiroshima on August 18, 1945. He carried with him some rolls of film, which were given to him as severance pay. He found that 13 members of his family had perished, including his mother, his brother and his brother’s family, and his sisters.

He once recalled, in an article that appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun on August 3, 1968: “I was just going to take photos of the places where my relatives died...but then I wanted to take photos of another place, and then another. That’s how I went deeper and deeper into this.” He ended up taking photos of grave markers all over the Hiroshima delta.

In those days, the Chugoku Shimbun company, whose headquarters had been gutted by fire in the A-bomb blast, had difficulty obtaining camera film. Mr. Sasaki was able to get rolls of film, 100 feet long, by serving as a guide for photographers from overseas. While walking around the city with his camera, early in the morning, he was sometimes questioned by the police or stared at by others. Still, he continued capturing the evolving cityscape as it went through the process of post-war reconstruction. He made a base for his activities in the Motoujina part of Minami Ward, earning a living by taking pictures for tourists while persisting in his efforts to record Hiroshima in photographs.

Akira Matsuura, 73, a former city news reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun, was on friendly terms with Mr. Sasaki. Mr. Matsuura said he still recalls Mr. Sasaki’s words: “I took photos of gravestones of A-bomb victims, including my family’s plot. There weren’t any people in these pictures.” Through the viewfinder, he saw his lost relatives.

Aware of the suffering that was inflicted by the atomic bombing, he devoted himself to taking photos of silent gravestones, rather than images with aggressive anti-nuclear messages. This is why he went on taking photos of the A-bomb Dome. Mr. Matsuura introduced Mr. Sasaki to a documentary film director in Tokyo. With the help of this director, he held an exhibition of his work at Matsuya Department Store in Ginza, Tokyo in 1969, two years after the dome underwent a preservation project. The exhibition, titled “Hiroshima Diary,” was met by a strong response from the public.

In the brochure for the exhibition, Mr. Sasaki described his work in the ruins of the city: “I continued pressing the shutter, and before I knew it, I had taken 100,000 pictures. The negatives mean everything to me now.” Overcoming an eye disease, he remained an independent photographer, his words conveying pride in the way he chose to live his life.

The following year, Mr. Sasaki issued Hiroshima Since August 1945, published by the Asahi Shimbun. He later published a bilingual book titled Hiroshima Diary. He called for collecting and preserving photographs related to the atomic bombing, and the Association of Photographers of the Atomic Bomb Destruction of Hiroshima was formed in 1978. The association gathered 278 pictures from 20 people. Mr. Sasaki resigned from the group, and died of liver failure in 1980 at the age of 63.

While copies of photos held by the association attracted attention when they were exhibited at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Mr. Sasaki’s photos were given special praise. His wife Kiyomi, 85, preserved his work carefully. However, when she lent out some photos, on request, they were captioned incorrectly and others were never returned to her.

After consulting with his mother, now hospitalized, Mr. Sasaki’s son Yugo sent the first 507 photos and 20 files of negatives, in chronological order, for inclusion in the electronic archive. He made this decision to realize his late father’s wish. “I took these photos in the hope that they will be living witnesses to what happened,” Mr. Sasaki once said.

Expression “domed building” appears in U.S. military newspaper in August 1946

Name “A-bomb Dome” comes into general use in 1952, after end of occupation

In 1990, the City of Hiroshima said that it is not clear who began using the name “A-bomb Dome” and when, and suggested that citizens spontaneously began using this term, something now often quoted by the media. But is this really the case? In researching this part of history, I learned how the structure became known as the “A-bomb Dome” to Japanese and Americans alike.

According to the latest research, the atomic bomb exploded at a height of 600 meters above the ground, 160 meters southeast of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, a three-story brick building.

The Osaka edition of the Mainichi Shimbun, dated September 13, 1945, published the first photo involving the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and reported that the roof of the hall had been blown off. The Chugoku Shimbun, still in the process of reconstruction after the bombing, ran its first photo of the damaged building on June 8, 1946 in an article about an event which involved sketching the war-ravaged area. That same year, on July 6, the Evening Edition Hiroshima, published by another company, reported that a tower was erected in the Nakajima Honmachi district to comfort the souls of the A-bomb dead and said that the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall on the opposite side of the river was now in ruins. This was around the time that the city decided to turn the area into a park.

But when was the word “dome” first used to describe it? Studying English-language newspapers at the National Diet Library, I found a photo of the shattered structure in the August 6, 1946 Pacific Edition of the Stars and Stripes, an American newspaper for the armed forces. “Bomb exploded 800 feet over domed building,” it said. On the front page of the August 5, 1947 issue, it was reported that “Officials recently decided to preserve this building as a memorial.” This assumption, though, may have been made based on the decision to preserve the area by constructing a park. At the time, the preservation of the building itself had not been resolved.

In a booklet titled Tour of Hiroshima, The Atomic City, published by U.S. and British occupation forces, an illustration appears with a caption that refers to the structure as a “domed building” and explains that “everything within a radius of two kilometers from the hypocenter was completely burned.” The booklet was donated to Peace Memorial Museum in 2005 by a family member of a late British veteran who had visited Hiroshima in 1946.

Meanwhile, Hiroshima, the well-known account of the atomic bombing by John Hersey that appeared in the August 31, 1946 issue of The New Yorker, as well as the September 15, 1947 issue of Life magazine, which covered the first Peace Festival held by the City of Hiroshima, refers to the building as the “Industrial Exhibition Hall,” an English equivalent of the Japanese name.

The first usage of the word “dome” by the Chugoku Shimbun occurred in the issue published on August 2, 1947. In connection to the upcoming peace festival, the article said that “the damaged dome stands as if calling to the sky for peace.”

The “Ten Views of the Atomic Bombing,” selected by the city’s reconstruction division, did not include the former Industrial Promotion Hall in its list. It was included, though, in the list of “notable sites of the atomic bombing” that was proposed by an Australian serviceman who served as a consultant for the post-war reconstruction. As construction boomed, and the area around the hypocenter was transformed into a park, the rounded dome of the western-style building became a symbol of the atomic bombing.

In a Chugoku Shimbun article that appeared on August 7, 1949, which reported on the winner of the design competition for Peace Memorial Park, the dome was mentioned in describing the devastation of the atomic bombing. The article referred to it as “the dome of the former Industrial Promotion Hall, the wreckage of the atom.”

The expression “Atomic Bomb Dome” appeared in an editorial on June 23, 1950 on sites of interest in the city. However, after the Korean War broke out two days later, this term promptly disappeared. Was it because the expression ruffled the United States, which had declared the possible use of nuclear arms in this conflict?

In those days, such terms as “A-bomb orphans” and “A-bomb maidens” were used. Reflecting on these terms today, it must be said that they were thoughtless expressions, even though the word “A-bomb” was used to refer to the damage caused by the bomb.

A book of haiku titled Yoru (Night), published in September 1950, was found in the Peace Memorial Museum library. The book includes a haiku, or seventeen-syllable poem, titled “Kanatokogumo, Genbaku Dome ni, Arikuruu” (“Anvil cloud, at the A-bomb Dome, Ants Running Wild”) that was written by a high school teacher living in the city of Shobara in northern Hiroshima Prefecture. The teacher, named Fujii, entered Hiroshima shortly after the bombing and was exposed to the bomb’s radiation. (Mr. Fujii died in 2003.) His book was not included in the list of censored documents by the occupation forces, and it is believed to be the first time that the atomic bombing was described with the words “A-bomb Dome.”

Before the conclusion of the peace treaty between Japan and the United States, the Chugoku Shimbun of August 6, 1951, and Tokyo evening edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun of August 16 of the same year, carried aerial photos with captions referring to the structure as the “A-bomb Dome.” In August 1952, a book of photographs titled Genbaku Daiichigo, Hiroshima no shashin Kiroku (The First Atomic Bomb, Photographic Record of Hiroshima) was published by the Asahi Press. A double-page feature was titled “the miserable state of the ‘A-bomb Dome.’” An special edition of the magazine Kaizo (Reorganization), published that November, included a report headlined “A-bomb Dome” by Mitsuo Taketani, a nuclear physicist. (Mr. Taketani died in 2000.)

Finally, in 1952, after the occupation ended, the expression “A-bomb Dome” came into general use. In 1953, the City of Hiroshima used the term in a tourism map in a manual for city administrators. (Within the text, it was referred to as the former Industrial Promotion Hall.)

The New York Times of July 31, 1955, carried a feature article headlined “Hiroshima—Ten Years After.” “This wreck, formerly the stately Industrial Exhibition Hall, is preserved deliberately as a reminder and symbol. The stark hemisphere of burned twisted steel at its top suggested its new name ‘The Atomic Dome’.” This is when the name took hold both in Japan and the United States.

The A-bomb Dome has long served as a warning that the use of nuclear weapons can create terrible destruction. In 1996, it was added to UNESCO’s list of World Heritage sites as “Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome).”

(Originally published on June 5, 2007)