Survivors’ Stories: Osata Sumida, 96, Minami Ward, Hiroshima

Jun. 7, 2021

Felt powerless as uncle groaned in pain

Questioned himself about meaning of “peaceful life” but came to understand by working in fields

by Rina Yuasa, Staff Writer

Osata Sumida, 96, lost his uncle and other relatives in the atomic bombing. After World War II, he endured hardships such as difficulties in obtaining food. He has always given thought to the issue of what peaceful life truly entails while looking back on the war.

In August 1945, he was 20 years of age and a third-year student majoring in mechanical engineering at Hiroshima Technical Institute (now the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). His house in the area of Sendamachi 2-chome was scheduled to be demolished to make way for fire lanes in the city. As a result, he and his younger brother, a third-year student at Shudo Junior High School, went to stay at their relatives’ place in the area of Ajina (now part of Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima Prefecture). Mr. Sumida was the oldest boy of six siblings.

His father worked at the Hiroshima Army Clothing Depot. Because his job involved moving materials to a safer location, he, his wife, and three of their children moved to the present-day town of Tsuwano in Shimane Prefecture. Along with other school children, another son was evacuated to the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture for the sake of safety.

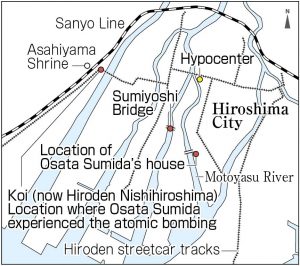

On the morning of August 6, Mr. Sumida went to his home, and when arranging things in the house, an air-raid alert was sounded. He took a train to return to Ajina and changed trains at Koi Station (now Hiroden Nishihiroshima Station). Soon, a flash of light pierced throughout the train, followed by a boom from the blast.

He instantly threw himself on the ground and thereby escaped death, but other passengers were covered with blood as glass shards were impaled in their faces and over their entire bodies. The location was 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. He thought a bomb must have been dropped in the vicinity and ran to the hill behind Asahiyama Shrine (now in Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward). Around noon, he was caught in thick, black rain before walking home.

Three days later, he boarded a train for Tsuwano. There, his mother Mitsuyo, then 44, wept and hugged him tightly. “I’m so relieved! How nice you made it here,” she said, worried because of the stories she had heard describing Hiroshima as being annihilated.

Two weeks after the atomic bombing, Mr. Sumida and his mother returned to Hiroshima to learn what had become of his uncle Tsunoru Kunihiro, then 42, and another relative Hisako Ishimoto, then 44. There, amid the smell of burning corpses lingering in the air, they saw people who had taken shelter from rain using galvanized iron sheets from where their toilets and bathrooms once stood. Bodies were drifting with the ebb and flow of the Motoyasu River, where Mr. Sumida used to play and catch shijimi clams. “It was such a shock to witness; I felt so terrible for everyone.”

They found Mr. Kunihiro at his home in the area of Takasu (now part of Hiroshima’s Nishi Ward). He had been at Sumiyoshi Bridge (now in the city’s Naka Ward), 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, at the time of the atomic bombing. He was groaning in pain as his entire body had been burned and become infested with maggots. A few days later, Ms. Sumida and his mother had to leave Hiroshima. “I was so despairing, I felt my heart would break,” he said. Mr. Kunihiro died the following month. Ms. Ishimoto’s body was never found. Mr. Sumida imagines she must have died a tragic death.

After the war, he moved to the village of Tokusa (now part of Yamaguchi City) in Yamaguchi Prefecture, in the hopes of securing enough food to get by. His family helped each other out and worked hard in the fields. He felt keenly that the vitality exhibited by plants such as potatoes and rice when they grew represented “peace.” “Although we were poor, I was most happy when I was with my family.” Around that time, he had an opportunity to learn about Christian ideas. He began to seriously rethink the militaristic idea of “dying for one’s country.”

Mr. Sumida later became an elementary school teacher, but he had to spend three years convalescing from tuberculosis. Later, when he was 37, he moved back to Hiroshima and began studying hydrodynamics at Hiroshima University. He began to be involved in what was known as the mingei (folk craft) movement, through which people worked to find beauty in the folk artwork rooted in the various local areas around Japan. The movement was promoted by the philosopher Muneyoshi Yanagi. Mr. Sumida served as leader of the Hiroshima Prefectural Mingei Association and, in 2007, held a national convention in Hiroshima of the Japan Mingei Association based on the theme “Mingei—Peaceful Life.”

Now he leads a tranquil life, caring for his wife Hideko Sumida, 89. “Respecting a diversity of cultures will lead to peaceful daily lives.” Those are the same words Mr. Sumida has always communicated to members of the Mingei Association.

(Originally published on June 7, 2021)