Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, evidence of victims remains 76 years after atomic bombing—Schools actively provided students as labor

Jul. 19, 2021

Escalating demands from prefectural government and military observed in First Girls’ School records of student mobilization

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

After the Pacific theater of World War II grew desperate for Japan in 1943, many third and fourth-year students at junior high schools and girls’ high schools under the prewar education system in Hiroshima were mobilized to work at military supply factories, and first and second-year students were mobilized to dismantle buildings to create vacant lots in preparation for the possibility of air raids. It is said that about 6,300 mobilized boys and girls were killed in the atomic bombing while engaged in such building demolition. Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (First Girls’ School) had the largest number of victims. Why did the school’s mobilization efforts of its students expand to such an extent? The Chugoku Shimbun sought clues about the answer to this question based on public documents and records of student mobilization archived at Funairi High School, located in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward and the successor to First Girls’ School.

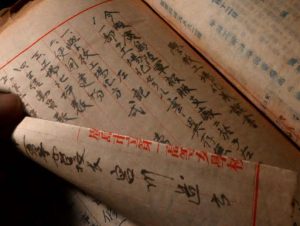

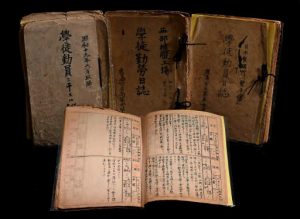

The principal’s room in Funairi High School has in storage two cardboard boxes filled with discolored brown documents. There are about 30 items inside the boxes, including files of public documents and other papers written during the period from December 1943 until just after the end of war. The documents contain a file of public correspondences numbering about 400 notices issued by military officers and the Hiroshima governor and mayor, and include reports filed by First Girls’ School to the governments and military.

“I was surprised that such a large number of actual documents have been archived. I can say these are not only historical materials conveying our school’s situation during the war but also a comprehensive record of student mobilization for the war effort in Hiroshima.”

Tomoko Yanagi, the high school principal, expressed astonishment. Ms. Yanagi had once worked at the school as an English teacher, but she was not aware of the presence of the files until two years ago, when she was assigned to the school again as vice principal.

In 1921, exactly 100 years ago, First Girls’ School opened in the area of Kokutaiji-cho (now part of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). Five years later, the school was relocated to its current spot. It became known for the grandeur of its school culture from early on, including its efforts involving the study of Western music. Because First Girls’ School was located 2.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, its buildings were partially destroyed in the atomic bombing but were not completely incinerated by the fires that raged in the city after the bombing. That may have been the reason why the documents survived. It is not clear, however, how the files avoided later being scattered or discarded.

Upon reading the documents one by one, it becomes clear how the prefectural government and the military intensified their orders to, and demands of, the school, and the reality that the school responded to the orders by actively providing its female students as support for the home-front and then as labor for the military effort. The documents also provide a glimpse into the circumstances of Hiroshima in those days as a military city, an area in which military facilities and factories were concentrated.

Based on a national government Cabinet decision made in March 1944, the determination was made that a student mobilization program would be implemented throughout the year, although the mobilization time-period had been limited until that point. Responding to the decision, a notice issued under the name of Hiroshima Prefectural Governor Sukenari Yokoyama (1884–1963) clearly indicated, “Manufacture and education will be unified through the process of student mobilization,” urging the schools to increase the scale of mobilization. Accordingly, First Girls’ School allocated advanced students to the naval dockyards in Kure City in May of that year and the following month dispatched fourth-year and older students to military factories in Hiroshima.

In August 1944, the school building was transformed into a school factory in which manufacturing and education were literally united. Households were forced to provide sewing machines to the school, and third-year students worked on production of military uniforms at school. There is a letter of acceptance dated July 30 written by Zoroku Miyagawa (who died at age of 74 in 1975), school principal at that time, to the Hiroshima Army Clothing Depot. It read, “I don’t have any objection about transforming the school into a factory.” Other records indicate that Mr. Miyagawa promoted the idea to the students by exhorting, “Whether women work or not will determine the outcome of the war.”

Military officials frequently held training sessions for the teachers. The school reported information on the teachers it felt it could send for such training to the department of student mobilization in the prefectural government and other such organizations.

Most of the notices addressed to the school were written under the name of the head of the internal affairs department of the prefectural government, but some were sent by the military or the municipal government. A notice written by Senkichi Awaya, then mayor of Hiroshima, dated September 29, 1944, instructed the schools to gather used tea leaves to address the issue of feed shortages for military horses. “We will hereby contribute to the enhancement of transport capabilities.”

The last notice released during the war, which the Chugoku Shimbun was able to confirm by recently reviewing a series of the documents, was titled “Re: Organization and formation of student corps when transferred to battle troop work,” issued by the commander of Hiroshima regimental district headquarters on August 1, 1945. The notice provided concrete instructions about the new organizational formation that included “work squads” and “gas-resistant squads.” Hironobu Ochiba, 44, chief curator at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, explained, “I assume this notice was issued to prepare for battles on the homeland. The document is proof that the military was trying to further promote militarization of schools.”

From the notice, it can be interpreted that Japan’s policy of continuing the war still had not changed even after a long time had passed since the war had brought tremendous hardship to the country. Only five days after the notice was issued, the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. On August 16, one day after the official end of the war, a notice regarding withdrawal of the mobilized students was issued under the names of the chief of the internal affairs department and the police commissioner of the prefectural government and sent out to schools.

Many third- and fourth-year students mobilized to work at factories

Some injured or died during production of weapons

Many of the documents stored at Funairi High School are records related to First Girls’ School students mobilized to work at factories. There are four books of records of student mobilization work penned by supervising teachers, as well as copies of reports assumed to have been submitted to the student mobilization department in the prefectural government at the time. The documents include detailed descriptions of how the female students were doing at the factories, as well as their working conditions.

Excerpts from one record include the following: “Weather: Sunny,” “Number of attendees: 103,” as well as, “A check-in ceremony was held. At the ceremony, the governor’s instruction (read by proxy), plant manager’s instruction, and military administrator’s congratulatory address were announced, and a motivational speech was delivered by the school’s representative.” The record was dated June 12, the first day fourth-year students from First Girls’ School were mobilized to work at a Japan Steel Works (JSW) plant in the area of Akifunakoshi-cho (now part of Aki Ward), after the full-year student mobilization effort was determined in March 1944. The writings in the record point to the excitement of teachers who wrote them, probably because a grand send-off ceremony had been held.

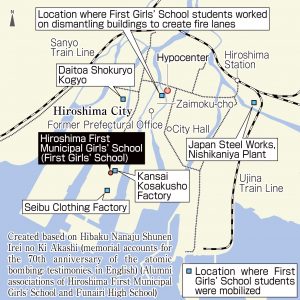

There are also other records of student mobilization to JSW’s Nishikaniya plant (now part of Minami Ward), and to a Seibu clothing factory located in the area of Funairikawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward). First Girls’ School students were forced to engage in hard work until the atomic bombing, which took place in the summer of the following year. Many students became injured from work at the weapons factory, largely because they engaged in work to which they were unaccustomed.

Files on student mobilization contain minutes of meetings in which the teachers negotiated with the factory management to seek improvements in the factory’s hygienic conditions and operators’ attitudes, as well as an organizational chart of the student corps that was reminiscent of a military organization. Another report file archives notices of students who became sick while on duty and died.

Kogiku Inou, 91, a resident of Hiroshima’s Naka Ward who was a third-year student at First Girls’ School at the time of the atomic bombing, started manufacturing machine-gun ammunition at JSW’s Nishikaniya plant in the June of her second year of school. Ms. Inou said, “I was only 15 years old, but I sometimes had to work the night shift, which was hard. We were in an unlucky year, as we virtually didn’t have any time to study. Children now are lucky.”

First- and second-year students mobilized to dismantle buildings for fire lanes

541 girl students died “that day”

The Hiroshima City government developed a six-phase plan to dismantle buildings starting in November 1944 to create fire lanes for the war effort in preparation for enemy air raids. The city government requested the volunteer fighting corps, primarily comprised of a municipality or company together with junior high schools and girls’ high schools in the city, to mobilize resources. Because the upper-class students were already working at military factories, first and second-year students were naturally chosen to be mobilized members of the student corps.

According to a chronological table of Hiroshima prefecture’s history, the Hiroshima governor and others decided to mobilize the volunteer fighting corps and student corps of 15,000 members for the demolition of buildings on August 3, 1945.

First Girls’ School students were assigned to work on the building dismantling efforts on August 5 and 6. The group was assigned to do the work near areas that were then known as Zaimoku-cho and Kobikicho (both are part of Naka Ward), which are located on the south side of Peace Memorial Park.

At 7:00 a.m. on August 6, 541 First Girls’ School students in the first and second years, as well as supervising teachers, gathered together, held a morning meeting, and began the demolition work. At 8:00, they had recess and took a break in front of the Seiganji Temple, which was located near the west side of the current Peace Memorial Museum’s main building. The atomic bomb then exploded in the sky above. They were about 500 meters from the hypocenter.

On that day, between 200 and 300 first- and second-year students were mobilized from each of Hiroshima Prefectural First Junior High School, Hiroshima Prefectural Second Junior High School, and Hiroshima Prefectural First Girls’ High School to an area within one kilometer of the hypocenter. Most of those students died. All the students from First Girls’ School were also killed. The remains of many of the students have yet to be discovered.

Valuable primary source complementing survivors’ personal notes

Scattering of materials must be prevented through storage at archives, elsewhere

Chie Shijo, Associate Professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Chie Shijo, associate professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University, who is an expert about the actual circumstances surrounding student mobilization, to better understand the value of the First Girls’ School documents and challenges associated with their archiving and utilization.

How should remaining public documents and records related to student mobilization be considered?

There are many unknown details about the student mobilization program carried out in Hiroshima, including the timetable leading up to student engagement in building demolition to create fire lanes for the war effort. The public documents and the records of the student mobilization effort represent valuable primary materials, as they were not edited by a third party and can be used to supplement survivors’ personal testimonies. Through such materials can be understood how schools addressed the situation.

When I was a curator at a museum in 2004, I was in charge of the special exhibit on student mobilization. Some of the First Girls’ School documents were on display at that time, but we didn’t have time to scrutinize the contents. Who gave the order to mobilize students, and how did the school cope with such directives? We should spend time verifying these kinds of questions carefully through cross-checking against the histories of Hiroshima City and Prefecture so that the information can be utilized as a lesson regarding how to not repeat the same error.

Survivor testimonies of A-bombing experiences highlighted in the effort to pass on war experience in Hiroshima to younger generations

Through implementation of the student mobilization program, the students’ rights to receive an education were violated because they had to work at factories for the manufacture of weapons and military supplies. In Hiroshima, the scale of mobilization was expanded, resulting in the deaths of many students who took part in the demolition of buildings. They were not only victims of the war but also main players cooperating in the war. The documents convey that a situation unimaginable today actually happened in the past.

The documents continue to deteriorate, however.

As the documents were made with poor quality paper during the war, they need to be stored under conditions in which temperature and humidity are expertly and properly controlled. It is impossible to ask the school to meet such storage requirements. In particular, there’s always a possibility that documents may be scattered or discarded, because teachers are frequently transferred in and out of such public high schools. The documents should be kept at governmental institutions such as Hiroshima Prefectural Archives or Hiroshima Municipal Archives. In many cases, school-related documents are one of a kind. So, once they are lost, it means the history itself ceases to exist.

There are new findings discovered in the materials depending on the person who is reading them. If they are not made available to the public, however, they are the equivalent of nothing. It is necessary for local intellectual resources to be utilized and made available to the public, as well as for the protection of personal information to be taken into consideration.

Chie Shijo

Graduated from the School of Letters, Arts and Sciences I, Waseda University. After working as a curator at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, she earned a doctoral degree at the Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Global Society, Kyushu University, in 2013. Appointed to her current position in April 2021. Originally from Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima.

Photos of materials taken by Hiroshi Takahashi

(Originally published on July 19, 2021)