Hiroshima, 70 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Rebirth of the City, Part 1 [1]

Jul. 23, 2015

Part 1 [1]: Nursing students devote themselves to relief efforts

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

On August 6, 1945, one single bomb dropped by the United States stole away the lives of scores of people in Hiroshima and completely decimated the city. The 70th anniversary of that day is now looming. Today there are high-rise buildings in the city center and greenery enjoyed by the inhabitants. After the bombing, some began making efforts to reconstruct the city. Others have worked hard to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons, the wish of the A-bomb survivors, though a path toward their elimination has not yet opened. This series focuses on the sense of mission found in each generation, following those who have passed the baton of A-bomb experience, and those who have grasped it from them.

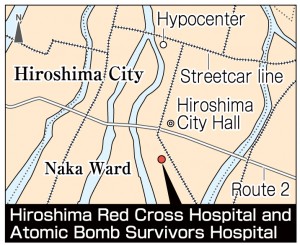

The staff of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, located in Naka Ward, have long been devoted to providing medical care for the A-bomb survivors. As former nurse Nobuko Hayashi, 87, a resident of Saeki Ward, stood on the grounds of the hospital, she recalled memories of that day 70 years ago: patients pleading for water, friends dying in misery, and herself at the age of 17 as she worked frantically in a white uniform covered in blood. “Back then, this site was a battleground,” she said.

Desire to “serve the nation”

In the spring of 1944, Ms. Hayashi left her parents in the village of Tsuna, Hiroshima Prefecture (now Miyoshi City), to undergo training in the nursing program at the Hiroshima branch of the Japan Red Cross, established at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. With militarism in the air, Ms. Hayashi had set her mind on “serving the nation.” According to documents compiled by the City of Hiroshima on the catastrophe, only 34 regular nurses were working at the hospital when the bomb exploded. Although there were about 250 soldiers already in the hospital, many staff members had been sent to provide aid on the front lines. But there were also 408 nursing students there. In 1945, Ms. Hayashi was a second-year student in the training program and serving as a regular nurse in one of the hospital wards.

On the morning of August 6, she was finishing a night shift without a wink of sleep. She was alone, washing bandages in a room on the third floor of the building made of reinforced concrete. It was located 1.6 kilometers south of the hypocenter. Then came a tremendous blast. Medical equipment flew off the shelves, apparently striking her, and she lost consciousness. When she came to, five or six hours later, she found that colleagues had carried her from the building. In a haze, she still felt concern for the patients under her care, thinking, “It would be terrible if something happened to them.”

Dusted with debris, Ms. Hayashi returned to the hospital ward to help evacuate patients to an underground shelter. Hearing cries, she dashed to the dormitory for the nursing students, located on the hospital grounds. Ms. Hayashi struggled to pull a classmate from the wreckage, but the girl was already dead after her head had been crushed by a pillar. A great wave of wounded were now in the lobby of the hospital’s main building. Begging for water, they grabbed at her legs. By the next morning, many of them were dead. She also found bodies in front of the entrance to the hospital, victims unable to reach the grounds inside.

The chaos continued. A total of 51 doctors and nurses, as well as nursing students, died at the hospital. These casualties amounted to 85 percent of the total staff, and still scores of patients continued streaming into the hospital, day after day. Ms. Hayashi herself suffered big gashes on her neck and arms, but she has “no memory of getting medical care.” When she was checking the temperature of a patient, she discovered that her temperature was actually higher. But she did not take time off. “I was desperate,” she recalled. “I only did what I could do for the lives of the people in front of me.”

Ms. Hayashi removed maggots from the patients’ wounds and applied ointment to their bodies. She even helped cremate the dead. Their ashes were placed inside large envelopes meant for x-rays. For several days she slept beneath the open sky, then began sleeping inside the hospital. In the middle of October, she finally took a week off and returned to her parents’ home. There, she abruptly collapsed. She was unable to move and she bled from her gums. A doctor diagnosed her with pneumonia, but Ms. Hayashi believes that the sickness was caused by the atomic bombing.

Devoted to sharing her experience

After completing the nursing program in the spring of 1946, Ms. Hayashi worked full-time at the hospital until that fall, then stopped for the next ten years. During that time she got married and gave birth to two sons. “I was like everyone else,” she said. “All my energy went into simply surviving.” Her family built a hut amidst the burnt ruins of the city. She supported her husband, who worked at a bank, by working part-time as a seamstress at home.

Eleven years after the atomic bombing, the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, specializing in the medical care of A-bomb survivors, was built on the grounds of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Around her, Ms. Hayashi saw people succumb to the aftereffects of the bombing, one after another. When she returned to work as a nurse, one of her former classmates in the nursing program committed suicide, troubled over the wounds she suffered from the A-bomb attack. Another friend developed leukemia. Her older brother died at the age of 42 and her younger sister died at 53. Both experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and both came down with cancer.

Ms. Hayashi continued her career as a nurse, working at general hospitals in and out of the city, as well as at a hospital of internal medicine near her home until she turned 60. Since reaching the age of 80, she has been devoted to sharing her experience of the atomic bombing at local schools. She said, “Today’s nuclear weapons are dozens, even hundreds, of times more powerful than the atomic bombs. If this evil is repeated, there will be no way for humanity to survive.” Ms. Hayashi is but one of many medical professionals who recognize the terrible consequences that nuclear weapons wreak on human beings. Her words carry weight. On July 15, she will visit another school to share her story, her sixth school visit this summer.

(Originally published on July 14, 2015)