Peace Features

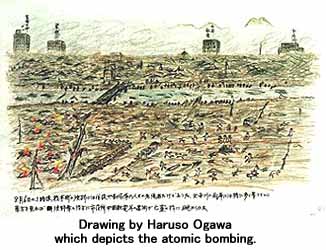

A-bomb Testimony by Haruso Ogawa

(March 6, 2008)

(Originally published on April 28, 2000 in the series "Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak")

At 8:15 on the morning of August 6, 1945, Hiroshima, my hometown, was instantly transformed into a city of the dead. It was a world of devastation and ash, with scores of men, women, and children killed indiscriminately due to war.

At 8:15 on the morning of August 6, 1945, Hiroshima, my hometown, was instantly transformed into a city of the dead. It was a world of devastation and ash, with scores of men, women, and children killed indiscriminately due to war.

At the time, I was working at a weapons factory on the outskirts of Hiroshima as a conscripted worker. I wasn't injured in the blast so I headed to my home in the city center, passing a wave of survivors who were fleeing from that area. As I hurried to my home in Zaimoku-cho, I felt as though I were wandering through hell, with thousands of dead bodies on both sides of my path.

When I reached the spot where my house had stood, and all the other houses in the neighborhood, I was stunned to find only a vast, scorched plain and struck dumb by the horror of war. In my wildest dreams, I could never have imagined such a sight when I left the house that morning. Although my mother had gone off into the countryside on an errand, my wife, Itsue, had stayed behind at home.

Burned bodies were lying everywhere I looked. Neighbors, who had engaged in lively discussions on the war effort when waiting out every air-raid warning in the air-raid shelter; students, who were mobilized to work in the community; and farmers, who had come down from their fields in the countryside to labor alongside the students--they were now all charred corpses, laying on the ground under the August sun.

And wandering among these victims were ghostly survivors, their bodies burned so badly that their gender was no longer recognizable, naked but for bits of tattered clothes. Their appearance was so horrific, with charred faces and hands held out like sleepwalkers, that I thought they were ghouls. Even their own family members wouldn't have been able to identify them. I wondered why they didn't seem to be heading to their homes--perhaps they were waiting to be rescued or waiting for death to take them. After spotting me through the slits of their eyes, they begged me for water.

How I wish the leaders of our nation were there to see those poor students! They were so young, barely in their teens, and what did they gain from their allegiance to the Emperor and their single-minded effort to win the war? The destruction of their lives. Small children had died, still holding hands, half-buried under a fallen wall. One girl, probably an older sister, lay covering her younger brother, as if trying to protect him from the blast.

People who lived in Zaimoku-cho gradually returned to the area from their workplaces in other parts of the city and evacuation sites on the outskirts of town. A chorus of anxious voices grew as people searched for missing children, parents, and siblings. One woman was holding a small, burnt body in her arms and sobbing--apparently, mother and child. Others were inspecting the charred corpses, one by one, their faces a mix of relief and worry. As the sun started to set behind the mountains off into the distance, the chorus of voices reached their peak.

The people gathered there, myself included, picked up the emergency kits which had somehow survived the destruction. In these kits were preserved foodstuffs, medicine, and other items. We ate the food but felt guilty about it. And when we found train passes, we placed them in a noticeable spot so relatives might notice the names.

That night stars filled the dark sky. They looked like scattered grains of silver sand. As I gazed up at them, I wondered if they were aware of this tragedy on earth. Due to the devastation, there were no mosquitoes in the air. Some bangs could be heard in the distance--something was exploding. Air-raid sirens went off, too, but they felt so far away, like they were the sounds of some other country. Voices calling out for help and for missing loved ones repeatedly broke the silence of the grim night. But as the night wore on, there were fewer cries.

I was unable to sleep, alone with my own heartbreak, though I was utterly exhausted both physically and mentally. The others around me pulled together branches and other debris to make makeshift beds--the ground was just too hot to lie down on directly. I heard no voices at that point, but I wasn't sure if they had fallen asleep or not. The sound of snoring came from somewhere, though.

I was lightly dressed and the night air was chilly. I piled some wood and started a fire to warm myself. What had happened to Itsue? I assumed she was dead and I should look for her remains.

I could see eerie blue flames still glowing across the landscape--the bones of so many bodies were burning up their phosphorus. As I watched the flames, images of the day came flashing back to my mind: the first charred bodies I saw that morning; naked schoolgirls packed into a water cistern, their arms raised to the heavens for help; corpses at the bottom of a well and in the air-raid shelters. At one point, a young woman had even begged me to kill her.

When dawn came and August 7 brought more of the same horror, I knew it wasn't just a dream. I was still sitting in the ruins of the city. When I looked about me in all directions, I saw a few gray concrete buildings, scorched but still standing in the rubble, chimneys alone but upright, and trees that had been reduced to solitary trunks. Flames continued to lick up from the ground here and there. Calls for help and for the missing, which had quieted during the night, were now heard again. The number of wounded seemed to have decreased--some may have been rescued during the night, others may have died. As scenes of the previous day replayed around me, tears streamed down my face, though I hadn't cried at all on the day of the bombing. When I saw members of a family reunite, as if returning from the dead, the moment was clouded by my tears.

I couldn't bring myself to go back to the ruins of my house so I wandered through the neighborhood. The riverbank was crowded with the dead bodies of students and other victims and the Shinbashi Bridge (today, Heiwa-ohashi Bridge) was completely destroyed. The injured were sitting among the dead in great numbers, staring at the river surface. I thought it was strange that they weren't making any effort to return to their homes.

Neighbors who were worried about family members and their residences returned from the places to which they had earlier evacuated. They gave me food, like the hard biscuits of that time, and cigarettes. When sirens went off some distance away, we looked up to find a U.S. B29 bomber, its silver wings glittering, flying south in the clear blue sky. The people around me yelled in warning and scrambled for shelter, but I didn't feel frightened at all. I just sat there and stared at the plane. I even expected another bomb to fall, though dropping more bombs onto such a wasteland would have been meaningless. I was tempted to laugh out loud at the absurdity.

As darkness fell on August 7, I felt only hunger. I spoke with other survivors of our neighborhood and about ten of us decided to head to Koi, in the western part of the city, where one person had relatives. Along the way, everywhere I looked, there were gruesome sights.

The entertainment district around the Kotobuki Theater was particularly shocking. Following the streetcar tracks, we came across burnt-out streetcars with charred passengers still sitting on the seats. From time to time, a chilly wind blew. Fortunately, the Koi area had managed to escape the firestorm.

I obtained a “casualty certificate” and two rice balls at a police station. Like a hungry beggar, I sat there on the ground and wolfed them down. At the Koi train station, a train was puffing smoke, but no one could be seen inside. When we reached our destination, a house sitting on a hill, I was able to receive a meal and spend the night. Still, I was unable to sleep and I gazed up at the stars through cracks in the roof.

The next day, August 8, was again blazing hot. I returned to the ruins of my old house in the same land of the dead. Surviving neighbors also came back to inspect the sites where their houses had stood.

I found a shovel and began to dig through the smoking rubble. With each jab into the embers, flames sprang up and I could feel the heat through the soles of my canvas shoes. A small clock rolled out from the rubble. It was burned but had retained its shape and the hands were frozen at 8:30. My house was apparently reduced to ashes at that moment.

I continued digging and I finally turned up a pile of white bones. I had no clear sign that it was her, but I was sure these were the bones of my wife, Itsue. My sweat and tears trickled down onto the hot bones and sizzled. I picked them up, hot to the touch, and placed them into a bowl. I then wrapped the bowl with a cloth normally used for lunch boxes.

At that moment, the tension that had kept me going drained away and I collapsed to the ground. My body was exhausted and numb, as if my spirit itself had fled. Lacking all emotion, I watched the people moving around me.

I had nowhere to go but back to my parents' home in the countryside. Though nothing remained of my house and my neighborhood, I said goodbye to my memories and to the people I was with for the past three days. With my wife's bones on my shoulder, I trudged through the wasted city, the horizon wide open now that so much of the world had simply disappeared.

Hiroshima's rise to prosperity, and its ruin to ash, are both tied to its role as a military city. Can Hiroshima be reborn from the rubble? Can life again grow in the debris? But as long as the war wages on, Hiroshima will be abandoned as a barren wasteland. And every city in Japan may experience the same fate that Hiroshima has suffered.

Where can we go to live in peace? Is there anywhere on this earth we can live? And it's all due to reckless war.

Tomorrow I will bury the remains of my wife in the ground of her hometown--such small consolation is all I can give.

Itsue Ogawa, 21, was crushed under the wreckage of her home in Zaimoku-cho when the atomic bomb exploded. Her husband, Haruso, who had been assigned to factory work, found her remains on August 8, 1945. Itsue and Haruso were from the same small town in Hiroshima Prefecture and were married in February 1944. They lived together with Haruso's mother in Zaimoku-cho. After the war, Haruso remarried. His eldest son, Kiyoshi, recalls, “For many years, my father took me to Peace Memorial Park on August 6 to offer prayers at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. I have vivid memories of him crying there. I had seen drawings he made of his memories of the atomic bombing, but I wasn't aware of his testimony kept by the city of Hiroshima. When I discovered the depth of his sorrow, I shared his story with my own children.”

Haruso Ogawa passed away in 1996 at the age of 83.