Contemplating the present and the future

New directions for peace education

What is "peace education" ? In Hiroshima, students in school learn about the day the world's first atomic bomb was dropped. This is so-called "atomic bomb education".

At the same time, there has been a recent movement to view peace education in the context of the world today. For this issue, the junior writers took part in a workshop led by a professor at Kobe University, Ronni Alexander, who specializes in peace studies. In addition, we investigated the activities of some teachers in Hiroshima who are engaged in peace education that focuses on a peaceful future for the world.

Atomic bomb education and peace education. Learning from the past and pondering the present and future. When both views are included, the result is more effective education. In this issue, we'll share our findings.

|

Professor Alexander's workshop We took part in Professor Ronni Alexander's workshop. She leads various peace education programs, and we experienced one of them. For about two hours, we enjoyed learning about peace through games and stories. Workshops like this are different from formal lectures because they provide the opportunity for students and teachers to explore issues together as equals. (Chinatsu Kawamoto, 14) |

Click to listen to Professor Alexander's talk about "Popoki" |

The junior writers express their opinions by touching points on the string.(All photos on this page were taken by Shiori Kosaka,12.)

Click to watch each part of the workshop.   |

(1) To what degree is Japan at peace? First, Professor Alexander introduced a long string which we used to express our opinions. For example, when she asked, "Is Japan at peace?" we could answer by touching a point on the string: for "yes" we touched the left end, for "no" we touched the right end. And we explained our reasons. I was impressed by her question, "Is peace simply the absence of war?" For this question, everyone touched the middle of the rope. I explained that it might depend on each person's feelings, while other members of our group shared their own reasons. It was interesting to hear these different ideas. |

Professor Alexander (right) reading the book.   |

(2) What is the "color" and "taste" of peace? Next, Professor Alexander read a book to us called "Popoki, What Color Is Peace?" And she asked us our opinions about the color of peace and what peace tastes like. Since questions like these don't have a single right answer, I found answering them more difficult than a math problem. But eventually, I felt free to share my ideas. |

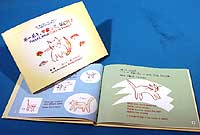

"Popoki, What Color Is Peace?"

Discover your own answers

A cat named Popoki is born with blue eyes but the color changes to green and then gold as he grows up. This is how the book begins and it suggests that the color of peace might appear differently depending on one's viewpoint.

Professor Alexander wrote this book and published it in May. The story follows Popoki's life and the Japanese text is accompanied by the English translation.

The idea of peace is expressed through everyday things. The sound of Popoki bouncing about might be the sound of peace and her favorite food might be the taste of peace.

The book poses various questions through Popoki's life, including his past as a homeless stray. One such question is "Can a society be at peace if it doesn't really respect life?" These questions grow in difficulty and the book offers no easy answers.

My impression is that the book wants to convey the idea that it's important to search for your own answers to these kinds of questions. (Haruna Tanabe, 17)

| |

A junior writer explains the picture. |

(3) Our own animal story The last exercise involved making up a story with an animal as the main character. We shared our ideas and drew a picture from the story we invented. The story raised the question "Can there be peace when human beings injure elephants to obtain their ivory?" And this led to other questions, such as "Are poachers solely to blame? What about people who buy ivory?" |

Sharing thoughts about peace

We enjoyed Professor Alexander's workshop and afterwards shared our impressions.

At first, we were confused about being asked our opinions. One person said, "I didn't understand what it meant to 'feel peace'."

Although we found it hard to describe peace directly, while discussing the children's book we came up with images like "peace is the sweet smell of syrup" and "peace is like fluffy clouds."

At school we learn about the horror of the atomic bomb, but generally just by listening to speakers. In this workshop, though, we were able to discuss how we ourselves might have a positive impact on these problems.

We especially enjoyed making up a story together because it was something new and fun for us. And since there are no "right" answers in this kind of activity, it meant we had to speak up to express our opinions. (Hayato Yoshioka, 15)

Looking closely at life around you

In the past year, Professor Alexander has held more than 30 workshops about peace using "all five senses".

She uses the story of Popoki, inspired by her experience with a stray cat that she brought home from a park 15 years ago. Although Popoki died two years ago, Professor Alexander has kept her friend's memory alive through a book that challenges children to think more deeply about peace.

In the past, she lived in Hiroshima for five years. She remarks, "Only the A-bomb survivors can truly convey the terrible reality of the atomic bomb. The next generation can't really share the experience in the same way." In this regard, Professor Alexander taught us to contemplate peace from our own perspective in the present.

She added, "In fact, all your subjects in school and all aspects of your lives can be linked to the idea of peace." (Shoko Tagaya, 17)

|

Ronni Alexander Born in the United States in 1956. After graduating from Yale University in 1977, she worked at the Hiroshima YMCA for five years. She became a professor at Kobe University in 1993 and her area of expertise is Peace Education. |

|

Courses on humanity and peace Thinking about poverty and bullying Hiroshima Institute of Technology, Junior High School and Senior High School

These two schools in Hiroshima offer a unique course in "humanity" at every grade level. The aim of the course is to empower students to act in ways that can create a more peaceful world. We joined a class led by the teacher, Haruki Nonaka, 54. First, the students made a list of things that are obstacles to a more peaceful world. Then they crossed out the items that could be overcome through their own cooperation. The full list had 42 items-such as hunger, racism, and websites that encourage suicide-and 19 of these were crossed out. "You eliminated many more than I expected," said Mr. Nonaka. He told us his aim for the class is to "not just share knowledge, but motivate students to change the world". This course on "humanity" is based on the idea that "The preciousness of life is not only impacted by nuclear weapons and war; we must think about such issues as poverty and bullying, too." And so classes include activities like touching the placenta of a woman who has just given birth and distributing biscuits to everyone in class in unequal portions to feel the gap between the world's rich and poor. (Hayato Yoshioka, 15, Shiori Kosaka, 12) Topics beyond the atomic bomb A research group of junior high school teachers in Hiroshima

A group of junior high school teachers in Hiroshima is developing a new course on "peace". The group is studying a range of peace-related topics, such as poverty and landmines. This research group on peace education currently has five members. It was established in 2005, the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombing, and the teachers share their research with students. Recently, they discussed "child labor" involving children in Ghana who are forced to harvest cacao which Japan then imports to make chocolate. This topic was proposed by Tomoyuki Kato, 53, a teacher at Jonan Junior High School. He remarked, "Our lives are supported by depleting the natural resources of other countries on the backs of their cheap labor." The teachers are eager to share a wider range of peace-related topics within a dwindling number of peace education classes. They feel that, traditionally, these classes have overemphasized the atomic bomb at the expense of other important issues. Kimihiko Watanabe, 54, a teacher at Eba Junior High School, says, "There has been too much emphasis on August 6th alone. We need to think about peace from many angles in our lives." (Kotaro Tsuchida, 14) |