StreetcarsCarrying courage and kindness for 100 years

Next year, 2012, will mark the 100th year since streetcars began operating on the streets of Hiroshima. The streetcars were also running on August 6, 1945, the day Hiroshima suffered the atomic bombing. Although the streetcar system and the work force were both hit hard by the blast, part of the system was restored three days later. It is said that these streetcars which resumed operations provided the people of Hiroshima with encouragement in the reconstruction of the city.

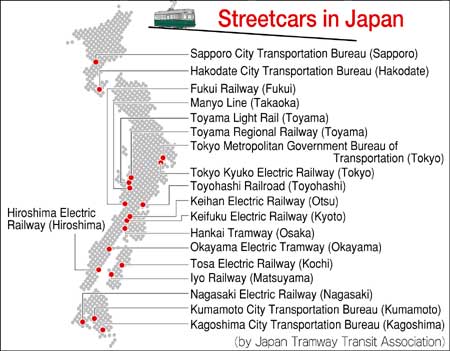

Later, the rise of motor vehicles left streetcars endangered, but today streetcars are viewed favorably as eco-friendly vehicles that produce no direct carbon emissions. Attaching multiple cars makes it possible to transport many passengers at one time and the design of the cars, with their low floors, enables easier access for wheelchair users and passengers pushing baby carriages. In Hiroshima, especially, you can see a variety of styles of streetcars, including old-fashioned cars bumping along and the latest of the longest streetcars in Japan, measuring over 30 meters in length.

In this issue of Peace Seeds, we look at activities seeking to hand down the history of the A-bombed streetcars as well as a new type of streetcar system designed to be both eco-friendly and people-friendly, the Light Rail Transit (LRT).

|

| An A-bombed streetcar travels through the city. |

First streetcar runs 3 days after bombing, 2 A-bombed cars still in operation

Of the 123 streetcars running in Hiroshima at the time of the atomic bombing, 108 were damaged by the blast. The work force of the streetcar system, totaling 1241 people, suffered heavy losses, too, with 185 dead and 266 injured. Despite such conditions, operations between Koi (Nishi Hiroshima) and Tenma (present-day Tenma-cho) were restored three days later.

Two A-bombed streetcars still amble the streets today, cars number 651 and number 652. At the time, they were the latest streetcar model. Since they were produced, these streetcars have logged roughly 2.6 million kilometers, which is equivalent to circling the earth 65 times. Makoto Idegahara, 53, the general manager of the tram transportation planning group of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company Ltd., told us: "As long as replacement parts for these streetcars are available, we can continue operating them."

However, the A-bombed streetcars, which have run the roads for 70 years, don't have the power and acceleration of the newer models. In addition, drivers can operate the newer models with one hand, while the old A-bombed streetcars must be driven using both hands. The old streetcars lack a brake meter as well, so they require an experienced and skillful driver.

One driver, Masafumi Takayama, 49, said, "When I hear about the atomic bombing, it makes me think about that day. I'm more present when I'm out driving and I feel more appreciation for the peace we have now." He smiled and added, "I like operating the old streetcars, including the A-bombed cars, as they give me the feeling that I'm really the one driving." (Sayaka Azechi, 16, and Naho Shigeta, 13)

At the Hiroshima City Library you can find books about the A-bombed streetcars, which have been published by the Hiroshima Electric Railway.

A-bomb account shared in streetcars縲 繝サ繝サ繝サ

繝サ繝サ繝サ

|

| Riding an A-bombed streetcar, Mr. Shimohara (left) shares his account of the atomic bombing. |

Takashi Shimohara, 81, lives in the city of Etajima and heads the association of A-bombed school teachers of Hiroshima Prefecture. Mr. Shimohara was 15 when he experienced the atomic bombing. For more than ten years, he has shared his account of the bombing with elementary school and junior high school students while riding in the A-bombed streetcars. With the wish that the children will take over efforts to oppose war, nuclear weapons, and discrimination, Mr. Shimohara details the reality of the bombing to them.

At the time of the blast, he was a student at the Second Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (present-day Kanon High School). He was in the hall at the school's entrance when the atomic bomb exploded. He saw a flash, and then found himself under the collapsed ceiling. He has memories of the following day in which he saw the dead in streetcars, still holding a strap or sitting in a seat.

The streetcars, though, also remind him of how the people of Hiroshima rose up to reconstruct the city in the aftermath of the bombing. Even today, he finds encouragement in the A-bombed streetcars. He hopes they will be preserved forever as a symbol of the city's revival. (Megumi Iwata, 17, who also served as aphotographer)

Plays written about A-bombed streetcars縲 繝サ繝サ繝サ

繝サ繝サ繝サ

|

| Mr. Ito writes plays about the A-bombed streetcars. (Photo taken by Yuka Iguchi) |

Takahiro Ito, 72, is a resident of Hiroshima and a former school principal. He has written four plays on the subject of the A-bombed streetcars. He chose to write about the streetcars, which began running again only three days after the atomic bombing--and are still used today by many--because "The people of Hiroshima love the streetcars."

The A-bombed streetcars still travel the streets of the city. "The history of the streetcars extends from the day of the bombing to today, and they're still hanging on," Mr. Ito said. "I would like people to be aware of all the effort that has gone into preserving these old vehicles."

Mr. Ito began writing his plays in 1969 when he was a teacher at Funairi High School and became the head of the drama club. His drama club performed at a nationwide gathering and had the opportunity to watch the original plays presented by other schools. The Funairi students were inspired by this experience and told him, "Our school is in Hiroshima, so we want to perform plays about Hiroshima's experience." Mr. Ito stressed, "When the students use their own bodies to perform these plays, they can touch the atomic bombing of Hiroshima as if it was their own experience. This can help hand down Hiroshima's experience to younger generations." To date, Mr. Ito has written 40 plays and all his scripts involve the atomic bombing. He has plans to write more, too. (Junichi Akiyama, 15, and Arata Kono, 14)

|

Synopsis of two of his plays

縲 "The Lights on the Streetcar Rails"縲Ninety percent of the streetcars were destroyed in the atomic bombing, and many streetcar workers died, too. But the survivors worked hard to restore the system, and the first streetcar started operating again only three days after the blast. "My Father's Streetcar"縲Jun, a high school student, is egged into sneaking into a streetcar shed and there he encounters an A-bombed streetcar. His father, now dead, was a streetcar driver. On the day of the bombing, Jun's father was absent from work, due to injury, so a female student took his place and drove his streetcar. In the wake of the blast, his father went searching for the girl and the radiation exposure resulted in leukemia. (Yuka Iguchi, 15)

|

|

| "Green Mover Max" is the latest streetcar model on the city streets. |

CO2 emission is one-fifth that of a car / Grass planted along railways

According to the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company Ltd., the amount of carbon dioxide emitted when a streetcar carries a person 1 km is 9g (as of 1999). This is equivalent to one-fifth of the amount when a private car is driven. The company has also planted grass along the railway from Hiroshima Port to Kaigandori, instead of laying asphalt or stone, and this helps keep the ground from heating up in the summer.

Still, Japan's eco-friendly streetcars once came to be in danger of dying out. In the early 1960s, automobiles were allowed to drive atop railway lines, and this hindered streetcars from maintaining their operating schedule. As a consequence, people began to view streetcars as an inconvenient form of transportation. Across the country, a number of streetcar systems were discontinued, one after another.

Streetcar companies appealed to the police, which has authority over the nation's roads, to prohibit cars from driving on the railways. Around this time police administrators were in Europe on business. They observed the flourishing streetcars there and decided to again ban automobiles from using streetcar railways in Japan.

Back then, the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company Ltd. could buy streetcars at a reduced cost from Kyoto and Fukuoka, cities where streetcars were no longer being used. Even today, Hiroshima boasts a wide variety of streetcars from other parts of Japan, and the system has been dubbed a "moving transportation museum." Currently, Hiroshima has 298 streetcars, the largest number of any city in Japan. Hiroshima streetcars also carry the largest number of passengers each day, with roughly 100,000 people riding the various lines (not including the Miyajima line).

In 2012, Hiroshima will mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of its streetcar system. The Hiroshima Electric Railway is now pondering how the system could be made even more convenient by altering some routes, such as connecting Hiroshima Station and Inarimachi or having streetcars run on Peace Boulevard. (Naho Shigeta, 13)

|

|

|

Toyama |

introduces LRT, increases passengers |

|

| The streetcars of the Toyama Light Rail feature a barrier-free design. (Photo is courtesy of Toyama Light Rail) |

In 2006, Toyama Light Rail began full-scale operations, the first in Japan, of the new "Light Rail Transit" (LRT) system.

Before this system was launched, when construction was carried out to elevate the local railways and bullet trains lines of Toyama Station, the question of elevating the JR Toyamaminato line was also discussed. Because the number of passengers using this line had been declining, the number of trains was decreased as well. The upshot was inconvenience for riders and a further drop in use. It was a vicious circle.

With the aim of revitalizing the city, Toyama decided to convert part of the train line to a tramway. Toyama Light Rail was installed and now streetcars run every 10 minutes in the morning and every 15 minutes during the afternoon and evening. The fact that the system features a barrier-free design, and operates for longer hours than in the past (with the last streetcar running until midnight), has enabled the city to successfully increase the number of passengers. On average, 4,800 people use the system each weekday, double the number of passengers from before. The Light Rail fare for senior citizens, 65 and older, is 100 yen, half the adult fare. This has helped increase the number of older passengers, 60 and over, to a level 3.5 times what it was in the past.

In the future, a new line will be established under the elevated Toyama Station in order to connect with another streetcar which runs on the south side of the station. Passengers will then be able to travel to the city center, located on the south side of the station, without changing streetcars. (Yuka Ichimura, 15)

|

Freiburg, Germany |

Streetcars contribute to lower rate of car ownership |

|

| A streetcar operating in Freiburg, Germany |

Freiburg, a city located in southwestern Germany, is known as that nation's "eco-capital." With a population of 220,000, it has promoted streetcars as the heart of its transportation system.

There are four streetcar lines in Freiburg, running a length of 36.4 km in total. To approximate the convenience of cars, the streetcars run every 7 and a half minutes. Since cars aren't allowed to enter the city center, residents must park their cars in parking lots near streetcar stations and then board streetcars to go downtown. Elevators at the streetcar stations provide easy access to trains and buses.

The system also offers a variety of unique tickets. One type of ticket can be used for as many as six people on holiday and another kind of ticket can be borrowed and lent. The grass planted along most of the railways contributes not only to a beautiful environment, but also helps to ease noise and vibrations. The streetcars run on solar energy and hydroelectric power.

Thanks to these efforts, the rate of car ownership in Freiburg is the lowest of the major cities in Germany, with 423 cars for every 1,000 people. (Chisa Nishida, 17, who also served as photographer)

- Light Rail Transit (LRT)縲LRT makes use of new technology, such as a low-floor design for barrier-free access and railways designed to decrease noise and vibrations. The system is one city planning measure intended to revitalize downtown areas.

- Moving transportation museum縲Hiroshima Electric Railway owns not only original cars but also streetcars from other parts of Japan, mainly cities in western Japan, where the use of streetcars was discontinued. The company has a total of 26 different types of streetcars, including cars that aren't currently in operation. The printed numbers on the cars indicate where the vehicles are from, such as 1900s from Kyoto, 3000s from Fukuoka, and 750s and 900s from Osaka. A car from Hannover, Germany (No. 238) runs the city streets, too. The two A-bombed streetcars run mainly on weekday mornings along the number 1, 3, and 5 lines. To learn the exact timetable, please contact the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company Ltd..

- Toyama Light Rail 縲A joint venture company composed of Toyama City, the Toyama Prefectural government, and private business. Construction costs for stations and railways, as well as streetcar maintenance, are covered by the local government, while Toyama Light Rail earns revenue through passenger fares for costs involving personnel and electricity.

|

Click to read the article "Junior writers venture abroad during summer vacation."

|