Haruki Nonaka, Part 3Wanting students to sense their potential

|

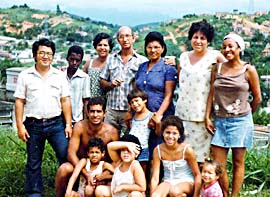

| Haruki Nonaka (far left) poses with members of the local community after a meeting of residents. (1982, Nova Iguaçu, in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil) |

Haruki Nonaka

Born in Osaka in 1953. He lived in Kure from the time he was a young child to the time he graduated from high school. After completing his studies in the Faculty of Humanities at Sophia University, he moved to Brazil in 1978. He studied theology and worked as a priest in Catholic churches in Rio de Janeiro and Para. He returned to Japan in 1991. He now works as a teacher of social studies at Hiroshima Nagisa Junior High and High School. In such classes as "Human Beings," "International Life," "Global Learning," and "Global Citizens," his workshops and lectures employ interactive learning methods.

Starting in 1978, I became a theological student and priest at Catholic churches in Brazil and Mexico.

One morning while I was living in the state of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, some children in my neighborhood came to me and told me there was a body in the street. I followed them and found the body lying there on the road. It was a shock to me, but I was even more surprised at the fact that the children were looking at the body with no qualms at all.

Such incidents were daily events there. People were reluctant to go to the police, even when a family member was murdered, due to fears of retaliation. In fact, I was robbed several times. On the bus, in a caf?, on the street, I was threatened with a gun and my money and possessions were stolen. The people lived their lives in constant danger.

In the Amazon region, I visited churches and assembly halls scattered in the jungle. Poor people from that area would travel many kilometers on the beds of trucks carrying milk or lumber to get into town. In the rainy season, the road was flooded. Ordinary cars couldn't handle such conditions and I would see people walking along with a heavy load or a sick child.

Poverty was a very serious problem. To address it, we held lessons in literacy and sewing at churches and meeting halls in the area, and we discussed the construction of such things as water and sewage services, electricity, roads, schools, and hospitals.

Facing the fact of such poverty, I became painfully aware of how powerless I was. Still, the people I saw would say to me, "Thank you for visiting us. Please come again." In the beginning, I wondered why they felt such appreciation toward me, but later, I noticed that they just enjoyed my presence. People mired in poverty lead difficult lives, but they have the power to overcome their difficulties when they work together with others. I was able to help just by spending time with them.

After I returned to Japan in 1991 and I began working at Hiroshima Nagisa Junior High and Senior High School, I came to feel that Japanese children, although their lives are rich in material things, aren't really living fully. To me, they aren't coming to grips with the real world and their own way of living life. The "Sarawak Study Tour" that was launched in 1998 is one way to address this problem. This year marked our 12th trip to Malaysia.

One of the students who took part in the tour eight years ago moved to one of the Oki Islands in Shimane prefecture after graduating from university. She's now working on the staff of the board of education there. She helped a local high school student enter a nationwide contest that called for conceiving a sightseeing plan. At first, the students weren't very adept at coming up with ideas and expressing themselves, but they made good progress in speaking before an audience and succeeded in winning the grand prize. My former student told me: "I want to convey to children that they can do something even when they think they can't. I want children who have never been off the Oki Islands to see possibility in their lives."

Before I went to Brazil, I had no motivation for anything and I had a hard time expressing myself. However, living among the Brazilian and Mexican people, I became free of something that was holding me back and I grew eager to study and work. I want my students to encounter the real world and their real selves. The fact that a former student of mine now has this same wish gives me great joy. It gives me new energy.