Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Time to seize public opinion to advance nuclear abolition

Aug. 5, 2015

by Yumi Kanazaki, Masakazu Domen, Jumpei Fujimura, Yoko Yamamoto and Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writers

Collectively turning their backs on the obligations of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) to pursue nuclear disarmament, the nuclear weapon states continue to defend their privileged position as possessors of nuclear arms. Meanwhile, Japan, which knows best the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons, still clings to a security policy in which the nation seeks shelter beneath the U.S. nuclear umbrella. But unless the countries that hold nuclear arms, and those that rely on them for security, are not driven to change the status quo, a world free of nuclear weapons can never be realized. The ray of hope amid this dilemma is the A-bomb survivors’ unshakeable belief that “no one should ever suffer as we did” and the might of public opinion which empathizes with this conviction.

On June 11, the day after a regular general meeting of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), nine A-bomb survivors visited the Foreign Ministry to present a letter of request to Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida.

The letter of request consists of seven demands, including withdrawal from the U.S. nuclear umbrella by shifting from the nation’s security policy based on nuclear deterrence and seeking the creation of a treaty to eliminate all nuclear weapons within a specified timeframe. When Toshiki Fujimori, 71, who was exposed to the atomic bomb as a one-year-old infant in the Ushita area of Hiroshima (today’s Higashi Ward), about 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, read out the letter of request, Takeshi Hikihara, the director general of the Disarmament, Non-proliferation and Science Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responded by saying, “It is Japan’s mission to lead the international community toward a world free of nuclear weapons. The experiences of the A-bomb survivors are the reason for this initiative.” Mr. Fujimori, is a resident of Chino, Nagano Prefecture, and the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations.

Conflicting opinions

This gives the impression that the Japanese government and the A-bomb survivors are facing in the same direction. However, in closed-door meetings, where frank opinions are exchanged, the views of the two sides differ starkly. “The government stubbornly insists on a stance in which it must first create an environment where the nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states will cooperate with one other. We heard those words over and over,” said Mr. Fujimori with a sigh, as he exited the Foreign Ministry offices.

On one hand, the government says that “we must eliminate nuclear weapons,” while on the other hand insisting that “the U.S. nuclear deterrent capability is necessary.” This is the stance of a country that has suffered the fate of two nuclear bombings, with the government adopting different attitudes and messages for different listeners. This is what the Chugoku Shimbun realized after our reports in the United States where a meeting of the Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee (two-plus-two security talks) was held this past spring.

Foreign Minister Kishida delivered a speech at the NPT Review Conference and made an appeal for the elimination of nuclear arms. On the same day, he attended the meeting to discuss the Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation, to be updated for the first time in 18 years. During the meeting, it was confirmed several times that the United States would defend Japan through “the full range of its capabilities, including U.S. nuclear forces.”

In U.S. government documents that have been released and remarks made by high-ranking officials, the United States clearly and frequently states that “the United States will maintain a nuclear deterrent capability to protect allied countries.” These allied countries total approximately 30 nations around the globe, including Japan and South Korea. Japan, the only A-bombed country, is “the pretext” for the nuclear superpower to possess nuclear weapons.

Meanwhile, frustrated by the fact that nuclear weapons are still held around the world, international public opinion has gradually changed. Current momentum calls for the creation of a new treaty that would outlaw nuclear weapons in order to close the loopholes of international law.

In the failed NPT Review Conference, a last-minute tug-of-war evolved over whether the final document would include a “nuclear weapons convention.” In these negotiations, Japan failed to make its presence felt. It would be safe to say that Japan was not in a position where it could even show its presence.

Should nuclear weapons ever be used, the effects will spill over borders. Japan, the only country that has experienced the inhumanity of nuclear arms, should initiate change and step outside the nuclear umbrella. Otherwise, Japan can never become a true leader in the abolition of nuclear weapons.

The problem of plutonium

There are a variety of challenges ahead, however. It is vital that Japan be able to ensure its national security through diplomatic and economic efforts. In addition, there is the formidable problem of plutonium.

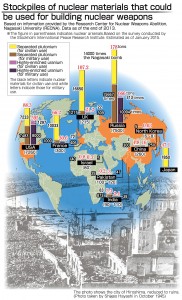

Nagasaki University’s Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) has published a map which shows the amount of highly-enriched uranium and separated plutonium amassed around the world. Surprisingly, along with the nuclear powers, which have developed nuclear arsenals, Japan possesses a tremendous stockpile of plutonium.

Among the non-nuclear weapon states, only Japan continues to reprocess spent nuclear fuel and extract plutonium on a commercial scale. This plutonium has accumulated without use, the stockpile now reaching 7,850 times the amount contained in the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

Professor Tatsujiro Suzuki, who is the director of RECNA and served as vice-chairman of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission in the Cabinet Office, asserted, “Even plutonium for civilian applications can be used for building nuclear weapons. Japan, the holder of such a stockpile, could make its neighbors wary of this fact even if it is not used, and as a result the regional security environment could grow increasingly unstable.” He also believes that Japan’s plutonium will become an obstacle in the quest to denuclearize Northeast Asia, including North Korea, through diplomatic efforts.

Some Japanese politicians regard the plutonium amassed in Japan as “potential nuclear armament.” It is certain that, if Japan were to try to withdraw from the nuclear umbrella under these conditions, neighboring nations would become suspicious of Japan possibly pursuing nuclear arms and the United States would surely step in to halt any attempt to withdraw. Despite having suffered from the effects of two atomic bombings, Japan again witnessed its land become contaminated with radiation emitted from the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi (No. 1) nuclear power plant in March 2011. It is now time for Japan to revise its nuclear fuel cycle strategy of handling plutonium as a “source” of fuel to generate nuclear energy and begin a discussion on how to safely dispose of this plutonium as “waste.”

The nuclear weapon states and U.S. allies, Japan included, have continually insisted that nuclear disarmament be pursued in a “step-by-step” approach that limits any radical shift in ridding the world of nuclear arms.

Modernizing nuclear forces

None of the nuclear powers, however, has clearly indicated when this process would begin and how long it would take to reduce their own nuclear arsenals to zero. Upon close examination, these nations are merely marking time or backpedaling. Disregarding their obligations to seek nuclear disarmament, as stipulated by the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), the nuclear weapon states are all rushing headlong to modernize their nuclear forces.

The United States boasts of its overwhelming nuclear capability. At the Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, the personnel charged with running the “Z machine,” which tests the performance of nuclear weapons, responded by asking why Hiroshima continues to oppose nuclear testing when these tests do not involve any detonations of nuclear arms. It seemed there was little understanding that it is the very effort to preserve nuclear weapons that is being criticized.

In the United States, various plans are now moving forward, including the development of next-generation cruise missiles carried by long-range bombers and a complete change of strategic nuclear submarines. According to estimates submitted to the U.S. Congress, if all of these plans are implemented, the total expenditures will reach one trillion dollars (approximately 123 trillion yen) over the next 30 years. This is the reality that has developed behind the notable words “a world without nuclear weapons,” once declared by President Obama.

Meanwhile, in Russia, which sinks deeper into conflict with other European nations and the United States over Ukraine, President Putin publicly alluded to preparations for the possible use of nuclear arms, ramping up the danger that a highly unstable and perilous atmosphere could emerge.

More than 90 percent of all nuclear warheads on earth are held by the United States and Russia. Before urging China and other nuclear powers to reduce their nuclear stockpiles, both the United States and Russia must take the initiative in reducing their own nuclear arsenals.

How, then, should these countries take on this task? There are clues which point to the right path.

The international community has begun to press the nuclear powers more forcefully toward reducing and eliminating their nuclear weapons. One such initiative is an appeal for the creation of a nuclear weapons convention, based on the inhumane nature of nuclear arms. Another initiative has been formulated by the Marshall Islands of the Central Pacific, a case that has been dubbed “the ant challenging the elephant.”

In 1954, a hydrogen bomb test conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll exposed Japanese tuna fishing boats, including the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), to radioactive fallout. The coral reefs around the test site were contaminated, and the people who once lived there are still unable to return to their homeland, though more than 60 years have passed since that day. Their appeal is imbued with heartbreak and bitterness. In April 2014, this small island nation filed lawsuits against nine nuclear weapon states at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for violating their obligations for nuclear disarmament.

The defendants are not only the five nuclear powers that are members of the NPT, but all nine nuclear weapon states, including India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea, which are non-members to the NPT. Tony de Brum, the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands, said, “It is the duty of a nation which suffered radiation damage to advise the nuclear weapon states to fulfill their nuclear disarmament obligations under the treaty.” Although the outlook for a successful court decision appears to be an uphill battle, Japan, another nation that has suffered the effects of radiation, as well as the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, should act in concert with the Marshall Islands. A new groundswell of support must rise.

Under the non-nuclear umbrella

A series of steady efforts has continued in Hiroshima to persuade those leading nuclear disarmament negotiations to gain firsthand knowledge of the A-bombed sites.

In June, the Hiroshima Office of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) invited young diplomats from five Southeast Asian nations, including Thailand, the Philippines, and Malaysia, to take part in its first seminar on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. Lorena Joy Banagodos, 39, from the Foreign Ministry of the Philippines, said, “I learned about Hiroshima when I was in elementary school, but I only realized the full impact of what happened here because of the atomic bombing by listening directly to the stories and experiences of A-bomb survivors.”

These five Southeast Asian countries are signatories to the Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone which bans the development and carry-in of nuclear weapons. In effect, they lie under a “non-nuclear umbrella” of their own creation. The Philippines and Malaysia, in particular, are known for their vocal support for a nuclear weapons convention.

The head of the UNITAR Hiroshima Office, Mihoko Kumamoto, expressed her hopes by saying, “The knowledge and human relationships that grew out of this seminar will strengthen the future efforts of the participants.” The diplomats who learn and gain a greater understanding of the tragedy of Hiroshima may encourage a more productive course of action not only to the nuclear weapon states but also to Japan, which continues to rely on the nuclear umbrella.

--------------------

Personal appeals

Takashi Hiraoka, 87, former Mayor of Hiroshima: Ease tensions with our neighbors

In the movement to create a nuclear weapons convention, “the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons” is now the focus. In 1995, during my tenure as the mayor of Hiroshima, I used this term “inhumane nature” when I made a statement about the illegality of nuclear arms at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands. That expression is now a rallying cry.

However, as I watched this year’s NPT Review Conference closely, I felt that Japan is moving backwards. Although the Japanese government issued a statement on nuclear abolition, there was a sense of detachment.

The term “inhumane” certainly describes the nature of nuclear weapons. Everyone can agree on this. Japan, though, is the only country to have experienced nuclear attack. So many people suffered terribly and then died. Many of the survivors are still suffering from the aftereffects of radiation and ultimately succumb to these effects. The appeal of the inhumanity of nuclear arms by Japan should be strong in its content which should carry the sentiments and voices of the A-bombed dead.

But in deference to the United States, Japan will not take further steps to advance a nuclear weapons convention. When Prime Minister Shinzo Abe addressed a joint session of the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives in April, he talked about “reconciliation” between the two countries without mentioning the atomic bombings. The United States still maintains that the atomic bombings were justified. Doesn’t this response disregard the voices of the dead?

If Japan appeals for the abolition of nuclear weapons while remaining under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, its stance lacks force and is unpersuasive. As I said in the Peace Declarations I made when I was mayor, Japan should step out from under the nuclear umbrella. Nevertheless, Japan has recently shown open hostility toward China and North Korea, making them wary and creating for itself an environment in which a nuclear umbrella is necessary.

If Japan becomes entangled in the world of deterrence, it will ultimately enter the world of nuclear armament. We have to reject that trend. We must first make a serious effort to ease tensions with our neighbors in Asia. This effort can lead to building peace.

Takashi Hiraoka

Born in Osaka in 1927. He joined the Chugoku Shimbun in 1952. He eventually became the editor-in-chief of the Chugoku Shimbun and the president of RCC Broadcasting, Co., Ltd., and was elected mayor of Hiroshima in 1991, serving two terms. His writings include Kibo no Hiroshima.

Keiko Nakamura, 42, associate professor at the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University (RECNA): Leadership toward nuclear abolition is needed

The Japanese government is making efforts to promote arms reduction and nuclear non-proliferation. For example, the government has designated high school and university students from Hiroshima and Nagasaki as “Youth Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons” to help spread these educational aims. The government has also formed the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI), a multilateral body, and has made important recommendations for improving the transparency of nuclear arsenals. Despite these efforts, Japan’s presence in the arena of international disarmament talks has been virtually non-existent.

Japan sees itself as a “catalyst” for bridging the divide between the nuclear haves and have-nots. But isn’t Japan’s approach overly passive? At the NPT Review Conference, when a fierce tug-of-war emerged between the nuclear weapon states and the nations pressing ahead for a nuclear weapons convention, Japan presented itself as nothing more than an onlooker. The fact is, it is difficult for Japan to take a productive stance as long as U.S. nuclear deterrence is part of its security policy.

The back-and-forth between China and Japan, over language in the final document calling for world leaders to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, made headlines in Japan. China’s position was clearly inappropriate with respect to the time and place. Still, we must look squarely at the factors that contributed to the lack of support for Japan’s proposal. The Japanese government’s call for a visit to the A-bombed cities, while it lies under the nuclear umbrella, lacks persuasiveness. If the call had been made by the A-bombed survivors, we could have seen a different development.

A regional effort to bring Northeast Asia, including Japan, closer to a nuclear-free zone and a decision to lead the movement seeking the global abolition of nuclear weapons--these are initiatives where Japan should step up and show resolve.

Among non-nuclear nations that have become impatient with the impasse over nuclear disarmament, the movement to create a nuclear weapons convention will likely continue to grow. Although such a trend might seem to be welcomed by Japan, in fact this nation is not a supporter of the movement. Can the Japanese people and the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki sway their government? The seriousness of residents of the A-bombed cities is being put to the test.

Keiko Nakamura

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1972. Received a graduate degree from the Monterey Institute of International Studies. After serving as the secretary-general of Peace Depot, an organization that makes recommendations on policies for a security framework not dependent on military force, she assumed her current position in 2012.

Haruko Moritaki, 76, co-chair of the Hiroshima Alliance for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (HANWA): Expand attention on all things nuclear

Mining and enriching uranium, working at nuclear power plants, developing and producing nuclear weapons; these things are not independent of each other, they are all related and together make up the “nuclear cycle.” At the same time, powerful interests are involved and intertwined. By focusing only on nuclear weapons themselves, it is difficult to realize their elimination.

The nuclear cycle is also a cycle that leads to damage from radiation. Depleted uranium weapons which are built from the remains of uranium enriched to create nuclear arms and nuclear fuel have caused serious internal exposure to people in Iraq and U.S. soldiers who returned from there following the Persian Gulf War. Also, in connection with uranium mines in India, the mine workers and the local residents are suffering health problems.

In Japan, too, a nuclear meltdown occurred at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. We, the citizens of Hiroshima, should expand our interest in all things nuclear on a much greater scale.

After the nuclear meltdown, renewed light was shed on the words “complete rejection of all uses of the atom, including nuclear power” and “the human race cannot coexist with nuclear weapons or nuclear power,” which were stated by my father (the late Ichiro Moritaki, then professor emeritus of Hiroshima University). He devoted his life to the movement against A- and H-bombs.

In the 1950s, my father did support the peaceful use of nuclear energy. However, as he learned about the reality of nuclear power generation and nuclear tests which were being conducted around the world, his anguish as a philosopher grew. After a critical look at his acceptance of nuclear power, he eventually arrived at a state of mind encapsulated by the words above.

Japan is now seeking to resume operations at the nation’s nuclear power plants as if we never experienced a nuclear meltdown. How seriously has Japan taken that nuclear catastrophe which took place in a country which had already suffered two nuclear bombings? How much soul-searching has it really done?

This autumn, the World Nuclear Victims Forum will be held in Hiroshima. People living in and around nuclear test sites and nuclear mines are invited to share their experiences. I’d like this to be an opportunity for us all to reflect on this disastrous nuclear damage as our own problem. If this can happen, the appeal from Hiroshima and Nagasaki could grow more universally persuasive.

Haruko Moritaki

Born in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, in 1939. She has been engaged in efforts to bring youth from India and Pakistan to Hiroshima and confront issues involving depleted uranium weapons. She is a member of the steering committee of the International Coalition to Ban Uranium Weapons (ICBUW).

--------------------

Until the very last nuclear weapon is gone

The worst, most inhumane weapons in human history were dropped above the heads of the A-bomb survivors, who have spoken out about their experiences to people around the world, exposing the scars that were seared onto their bodies and into their memories. Although almost 70 years have passed since then, a great number of nuclear weapons still exist in the world today.

The damage caused by the atomic bombs is not a thing of the past, but a fear that lingers to this very moment. This has been the appeal of the A-bomb survivors. And it is this appeal that has fueled recent global momentum for abolishing nuclear weapons from the perspective of their inhumanity. Since 2013, three international conferences have been held in Norway, Mexico, and Austria, where government representatives have discussed the potential consequences if nuclear weapons are used.

This possibility is considerably higher than people think and current momentum for nuclear abolition stems from such recognition. There are a variety of scenarios where a nuclear weapon could detonate, including the result of human error or negligent action; the theft of a nuclear weapon by terrorists or a cyberattack on a nuclear missile base; and a sudden nuclear strike in the midst of conflict. The current state of affairs, in terms of the possibility that nuclear weapons could be used, is considered more serious than a nuclear war scenario involving the nuclear superpowers at the time of the Cold War.

Of the nuclear warheads now held by the United States and Russia, about 2,000 from each country could be launched within just a few minutes following a presidential order. Meanwhile, India and Pakistan are targeting one another with nuclear weapons as a consequence of territorial disputes. Whatever the trigger, another Hiroshima and Nagasaki nightmare would be created if a nuclear weapon is ever used again.

“As long as even a single nuclear bomb or warhead exists, the possibility that nuclear weapons will be used one day remains.” This statement by Terumi Tanaka, the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), is not groundless fear-mongering. For this reason, the “non-use” of nuclear arms is not enough. These weapons must be eliminated.

Brad Roberts, a former senior official of the U.S. Department of Defense who oversaw the Obama administration’s nuclear strategy policy known as the “Nuclear Posture Review,” says that, in terms of the total deterrent capability, the role of nuclear weapons has become smaller. His remarks, however, do not square with the goal of total nuclear abolition.

Sugio Takahashi, the chief officer of the National Institute for Defense Studies, located in Tokyo, explains that deterrence under the current Japan-U.S. alliance is “like an onion.” This means that the surface is robustly covered with conventional weapons and a missile defense system which can be employed in actual warfare with less reluctance than using nuclear weapons. However, for situations where the skin of the “deterrent capability” is removed, powerful nuclear weapon are poised at the core.

On one hand, conventional forces dominate, both in quantity and quality, while on the other, nuclear forces are reduced in number, but are modernized and made more sophisticated. “As the portion of conventional forces grows larger, Japan should take on bigger roles. This is the U.S. view,” said Hirofumi Tosaki, a senior research fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs. The administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who promised the enactment of new security bills in his address before the U.S. Congress prior to their passage in the Japanese Diet, seems to act in accordance with the desires of the United States.

A spiral of mistrust cannot be controlled by weapons under the guise of deterrence. The appeal of the A-bomb survivors that “Neither nuclear weapons nor war must be allowed” has once again grown more persuasive.

With respect to the stability of the region surrounding Japan, current conditions in Northeast Asia must be faced squarely. Although China has declared a policy of “no first use” of nuclear weapons, it is steadily building up its nuclear capability. North Korea is pushing forward with its nuclear development program in order to defend its regime at all costs.

However high and thick the barriers are, to overcome them Japan must leave the nuclear umbrella and strive for the diplomatic denuclearization of Northeast Asia. Japan must work to advance both the local goal of creating a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the region by eliminating all nuclear weapons, and the global goal of realizing a nuclear weapons convention. But the first step is moving Japan’s politicians to act. Hiroshima and her citizens will continue to appeal for action until the day when the very last nuclear weapon is removed from this earth.

--------------------

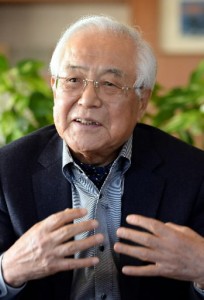

Interview with Terumi Tanaka, secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo): Make nuclear weapons a legal and moral stigma What do A-bomb survivors who have been appealing for the need to abolish nuclear arms, based on their experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, think about the continuing existence of nuclear weapons in the world? The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Terumi Tanaka, 83, the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo).

What are your thoughts regarding the current global state of affairs involving nuclear abolition?

I took part in the NPT Review Conference in New York in April and talked about my experiences of the atomic bombing there. I met some of the government representatives of nuclear weapon states in person and made an appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Some diplomats listened to my story with tears in their eyes.

I believe that these tears are heartfelt. However, as soon as the topic of the conversation shifted to their national security policies, their attitude changed completely. The French representative went so far as to say that the French people take pride in the fact that their country possesses nuclear weapons.

It’s incredible that a remark like this was made to an A-bomb survivor, isn’t it?

Among the five nations which have been permitted to possess nuclear weapons, there are tensions between both the United States and Russia, and the United States and China. However, in defending their “privilege” to possess nuclear weapons, it’s obvious that they are strongly united. I came away from the conference feeling that the hurdle to overcome is very high.

Possessing and depending on such inhumane weapons of mass destruction, which have caused us such tremendous suffering, is an utter disgrace, not a privilege or a point of pride. What is needed is international opinion that the possession of nuclear weapons is nothing more than a legal and moral stigma. We must create a nuclear weapons convention in order to make them illegal.

The appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons, by highlighting their inhumanity, has gathered momentum. What are your hopes for this trend?

This trend has been strengthened mainly by non-nuclear nations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). At the NPT Review Conference, Austria and other countries that are actively seeking the abolition of nuclear weapons released a joint statement which drew the support of more than 150 nations. The A-bomb survivors are greatly encouraged by this, because the “inhumanity” of these weapons is exactly what we have been insisting for so long.

Do you think the Japanese government is responsive to the A-bomb survivors’ appeal?

The government’s response will be limited as long as it maintains a security policy which relies on U.S. nuclear weapons. I have the same message for every country: The A-bomb survivors can wait no longer. I urge not only the nuclear powers, but also those nations which rely on an ally’s nuclear umbrella, to move past nuclear deterrence. It goes without saying Japan is one of those latter nations.

If the Japanese government would squarely face the effects and the suffering the atomic bombings have caused to its people, without downplaying them, I don’t think they would ever be able to say, “We still need nuclear weapons.” The government’s failure to do this is reflected in its stance of adamantly rejecting the applications for A-bomb disease certification made by A-bomb survivors, who contend that their illnesses are a direct result of the atomic bombings.

How can we spread the appeals made by the A-bomb survivors to the world?

The nuclear weapon states say that they won’t use the nuclear weapons they possess, while the countries huddling under the nuclear umbrella justify their reliance on these weapons. In this scenario, any nation can insist that they have the “right” to possess them, too.

As long as a single nuclear weapon exists, it could be used one day. We hope that no one will ever suffer as we did. This is why the aging A-bomb survivors have appealed for all nuclear weapons to be abolished while we’re still alive. If we face difficulties, we must deepen our ties with countries and people worldwide that are dedicated to nuclear abolition, and urge every nation to take action to advance the elimination of nuclear arms. We will never give up on this goal.

Terumi Tanaka

Born in the former Manchuria (in northeastern China) in 1932. While a first-year student at Nagasaki Prefectural Nagasaki Junior High School, he experienced the atomic bombing while at his home, 3.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. Five members of his family, including his grandfather, were killed. He was formerly an associate professor at the school of engineering at Tohoku University. In June 2000, Mr. Tanaka became the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations for the second time. He lives in Niiza, Saitama Prefecture.

(Originally published on June 21, 2015)

Collectively turning their backs on the obligations of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) to pursue nuclear disarmament, the nuclear weapon states continue to defend their privileged position as possessors of nuclear arms. Meanwhile, Japan, which knows best the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons, still clings to a security policy in which the nation seeks shelter beneath the U.S. nuclear umbrella. But unless the countries that hold nuclear arms, and those that rely on them for security, are not driven to change the status quo, a world free of nuclear weapons can never be realized. The ray of hope amid this dilemma is the A-bomb survivors’ unshakeable belief that “no one should ever suffer as we did” and the might of public opinion which empathizes with this conviction.

A-bombed nation has responsibility to step away from nuclear umbrella

On June 11, the day after a regular general meeting of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), nine A-bomb survivors visited the Foreign Ministry to present a letter of request to Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida.

The letter of request consists of seven demands, including withdrawal from the U.S. nuclear umbrella by shifting from the nation’s security policy based on nuclear deterrence and seeking the creation of a treaty to eliminate all nuclear weapons within a specified timeframe. When Toshiki Fujimori, 71, who was exposed to the atomic bomb as a one-year-old infant in the Ushita area of Hiroshima (today’s Higashi Ward), about 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, read out the letter of request, Takeshi Hikihara, the director general of the Disarmament, Non-proliferation and Science Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responded by saying, “It is Japan’s mission to lead the international community toward a world free of nuclear weapons. The experiences of the A-bomb survivors are the reason for this initiative.” Mr. Fujimori, is a resident of Chino, Nagano Prefecture, and the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations.

Conflicting opinions

This gives the impression that the Japanese government and the A-bomb survivors are facing in the same direction. However, in closed-door meetings, where frank opinions are exchanged, the views of the two sides differ starkly. “The government stubbornly insists on a stance in which it must first create an environment where the nuclear weapon states and non-nuclear weapon states will cooperate with one other. We heard those words over and over,” said Mr. Fujimori with a sigh, as he exited the Foreign Ministry offices.

On one hand, the government says that “we must eliminate nuclear weapons,” while on the other hand insisting that “the U.S. nuclear deterrent capability is necessary.” This is the stance of a country that has suffered the fate of two nuclear bombings, with the government adopting different attitudes and messages for different listeners. This is what the Chugoku Shimbun realized after our reports in the United States where a meeting of the Japan-U.S. Security Consultative Committee (two-plus-two security talks) was held this past spring.

Foreign Minister Kishida delivered a speech at the NPT Review Conference and made an appeal for the elimination of nuclear arms. On the same day, he attended the meeting to discuss the Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation, to be updated for the first time in 18 years. During the meeting, it was confirmed several times that the United States would defend Japan through “the full range of its capabilities, including U.S. nuclear forces.”

In U.S. government documents that have been released and remarks made by high-ranking officials, the United States clearly and frequently states that “the United States will maintain a nuclear deterrent capability to protect allied countries.” These allied countries total approximately 30 nations around the globe, including Japan and South Korea. Japan, the only A-bombed country, is “the pretext” for the nuclear superpower to possess nuclear weapons.

Meanwhile, frustrated by the fact that nuclear weapons are still held around the world, international public opinion has gradually changed. Current momentum calls for the creation of a new treaty that would outlaw nuclear weapons in order to close the loopholes of international law.

In the failed NPT Review Conference, a last-minute tug-of-war evolved over whether the final document would include a “nuclear weapons convention.” In these negotiations, Japan failed to make its presence felt. It would be safe to say that Japan was not in a position where it could even show its presence.

Should nuclear weapons ever be used, the effects will spill over borders. Japan, the only country that has experienced the inhumanity of nuclear arms, should initiate change and step outside the nuclear umbrella. Otherwise, Japan can never become a true leader in the abolition of nuclear weapons.

The problem of plutonium

There are a variety of challenges ahead, however. It is vital that Japan be able to ensure its national security through diplomatic and economic efforts. In addition, there is the formidable problem of plutonium.

Nagasaki University’s Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) has published a map which shows the amount of highly-enriched uranium and separated plutonium amassed around the world. Surprisingly, along with the nuclear powers, which have developed nuclear arsenals, Japan possesses a tremendous stockpile of plutonium.

Among the non-nuclear weapon states, only Japan continues to reprocess spent nuclear fuel and extract plutonium on a commercial scale. This plutonium has accumulated without use, the stockpile now reaching 7,850 times the amount contained in the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

Professor Tatsujiro Suzuki, who is the director of RECNA and served as vice-chairman of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission in the Cabinet Office, asserted, “Even plutonium for civilian applications can be used for building nuclear weapons. Japan, the holder of such a stockpile, could make its neighbors wary of this fact even if it is not used, and as a result the regional security environment could grow increasingly unstable.” He also believes that Japan’s plutonium will become an obstacle in the quest to denuclearize Northeast Asia, including North Korea, through diplomatic efforts.

Some Japanese politicians regard the plutonium amassed in Japan as “potential nuclear armament.” It is certain that, if Japan were to try to withdraw from the nuclear umbrella under these conditions, neighboring nations would become suspicious of Japan possibly pursuing nuclear arms and the United States would surely step in to halt any attempt to withdraw. Despite having suffered from the effects of two atomic bombings, Japan again witnessed its land become contaminated with radiation emitted from the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi (No. 1) nuclear power plant in March 2011. It is now time for Japan to revise its nuclear fuel cycle strategy of handling plutonium as a “source” of fuel to generate nuclear energy and begin a discussion on how to safely dispose of this plutonium as “waste.”

U.S. and Russia bear heavy responsibility for nuclear arms reduction

The nuclear weapon states and U.S. allies, Japan included, have continually insisted that nuclear disarmament be pursued in a “step-by-step” approach that limits any radical shift in ridding the world of nuclear arms.

Modernizing nuclear forces

None of the nuclear powers, however, has clearly indicated when this process would begin and how long it would take to reduce their own nuclear arsenals to zero. Upon close examination, these nations are merely marking time or backpedaling. Disregarding their obligations to seek nuclear disarmament, as stipulated by the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), the nuclear weapon states are all rushing headlong to modernize their nuclear forces.

The United States boasts of its overwhelming nuclear capability. At the Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, the personnel charged with running the “Z machine,” which tests the performance of nuclear weapons, responded by asking why Hiroshima continues to oppose nuclear testing when these tests do not involve any detonations of nuclear arms. It seemed there was little understanding that it is the very effort to preserve nuclear weapons that is being criticized.

In the United States, various plans are now moving forward, including the development of next-generation cruise missiles carried by long-range bombers and a complete change of strategic nuclear submarines. According to estimates submitted to the U.S. Congress, if all of these plans are implemented, the total expenditures will reach one trillion dollars (approximately 123 trillion yen) over the next 30 years. This is the reality that has developed behind the notable words “a world without nuclear weapons,” once declared by President Obama.

Meanwhile, in Russia, which sinks deeper into conflict with other European nations and the United States over Ukraine, President Putin publicly alluded to preparations for the possible use of nuclear arms, ramping up the danger that a highly unstable and perilous atmosphere could emerge.

More than 90 percent of all nuclear warheads on earth are held by the United States and Russia. Before urging China and other nuclear powers to reduce their nuclear stockpiles, both the United States and Russia must take the initiative in reducing their own nuclear arsenals.

How, then, should these countries take on this task? There are clues which point to the right path.

The international community has begun to press the nuclear powers more forcefully toward reducing and eliminating their nuclear weapons. One such initiative is an appeal for the creation of a nuclear weapons convention, based on the inhumane nature of nuclear arms. Another initiative has been formulated by the Marshall Islands of the Central Pacific, a case that has been dubbed “the ant challenging the elephant.”

In 1954, a hydrogen bomb test conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll exposed Japanese tuna fishing boats, including the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), to radioactive fallout. The coral reefs around the test site were contaminated, and the people who once lived there are still unable to return to their homeland, though more than 60 years have passed since that day. Their appeal is imbued with heartbreak and bitterness. In April 2014, this small island nation filed lawsuits against nine nuclear weapon states at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for violating their obligations for nuclear disarmament.

The defendants are not only the five nuclear powers that are members of the NPT, but all nine nuclear weapon states, including India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea, which are non-members to the NPT. Tony de Brum, the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands, said, “It is the duty of a nation which suffered radiation damage to advise the nuclear weapon states to fulfill their nuclear disarmament obligations under the treaty.” Although the outlook for a successful court decision appears to be an uphill battle, Japan, another nation that has suffered the effects of radiation, as well as the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, should act in concert with the Marshall Islands. A new groundswell of support must rise.

Under the non-nuclear umbrella

A series of steady efforts has continued in Hiroshima to persuade those leading nuclear disarmament negotiations to gain firsthand knowledge of the A-bombed sites.

In June, the Hiroshima Office of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) invited young diplomats from five Southeast Asian nations, including Thailand, the Philippines, and Malaysia, to take part in its first seminar on nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. Lorena Joy Banagodos, 39, from the Foreign Ministry of the Philippines, said, “I learned about Hiroshima when I was in elementary school, but I only realized the full impact of what happened here because of the atomic bombing by listening directly to the stories and experiences of A-bomb survivors.”

These five Southeast Asian countries are signatories to the Treaty on the Southeast Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone which bans the development and carry-in of nuclear weapons. In effect, they lie under a “non-nuclear umbrella” of their own creation. The Philippines and Malaysia, in particular, are known for their vocal support for a nuclear weapons convention.

The head of the UNITAR Hiroshima Office, Mihoko Kumamoto, expressed her hopes by saying, “The knowledge and human relationships that grew out of this seminar will strengthen the future efforts of the participants.” The diplomats who learn and gain a greater understanding of the tragedy of Hiroshima may encourage a more productive course of action not only to the nuclear weapon states but also to Japan, which continues to rely on the nuclear umbrella.

--------------------

Personal appeals

Takashi Hiraoka, 87, former Mayor of Hiroshima: Ease tensions with our neighbors

In the movement to create a nuclear weapons convention, “the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons” is now the focus. In 1995, during my tenure as the mayor of Hiroshima, I used this term “inhumane nature” when I made a statement about the illegality of nuclear arms at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, Netherlands. That expression is now a rallying cry.

However, as I watched this year’s NPT Review Conference closely, I felt that Japan is moving backwards. Although the Japanese government issued a statement on nuclear abolition, there was a sense of detachment.

The term “inhumane” certainly describes the nature of nuclear weapons. Everyone can agree on this. Japan, though, is the only country to have experienced nuclear attack. So many people suffered terribly and then died. Many of the survivors are still suffering from the aftereffects of radiation and ultimately succumb to these effects. The appeal of the inhumanity of nuclear arms by Japan should be strong in its content which should carry the sentiments and voices of the A-bombed dead.

But in deference to the United States, Japan will not take further steps to advance a nuclear weapons convention. When Prime Minister Shinzo Abe addressed a joint session of the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives in April, he talked about “reconciliation” between the two countries without mentioning the atomic bombings. The United States still maintains that the atomic bombings were justified. Doesn’t this response disregard the voices of the dead?

If Japan appeals for the abolition of nuclear weapons while remaining under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, its stance lacks force and is unpersuasive. As I said in the Peace Declarations I made when I was mayor, Japan should step out from under the nuclear umbrella. Nevertheless, Japan has recently shown open hostility toward China and North Korea, making them wary and creating for itself an environment in which a nuclear umbrella is necessary.

If Japan becomes entangled in the world of deterrence, it will ultimately enter the world of nuclear armament. We have to reject that trend. We must first make a serious effort to ease tensions with our neighbors in Asia. This effort can lead to building peace.

Takashi Hiraoka

Born in Osaka in 1927. He joined the Chugoku Shimbun in 1952. He eventually became the editor-in-chief of the Chugoku Shimbun and the president of RCC Broadcasting, Co., Ltd., and was elected mayor of Hiroshima in 1991, serving two terms. His writings include Kibo no Hiroshima.

Keiko Nakamura, 42, associate professor at the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, Nagasaki University (RECNA): Leadership toward nuclear abolition is needed

The Japanese government is making efforts to promote arms reduction and nuclear non-proliferation. For example, the government has designated high school and university students from Hiroshima and Nagasaki as “Youth Communicators for a World without Nuclear Weapons” to help spread these educational aims. The government has also formed the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI), a multilateral body, and has made important recommendations for improving the transparency of nuclear arsenals. Despite these efforts, Japan’s presence in the arena of international disarmament talks has been virtually non-existent.

Japan sees itself as a “catalyst” for bridging the divide between the nuclear haves and have-nots. But isn’t Japan’s approach overly passive? At the NPT Review Conference, when a fierce tug-of-war emerged between the nuclear weapon states and the nations pressing ahead for a nuclear weapons convention, Japan presented itself as nothing more than an onlooker. The fact is, it is difficult for Japan to take a productive stance as long as U.S. nuclear deterrence is part of its security policy.

The back-and-forth between China and Japan, over language in the final document calling for world leaders to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, made headlines in Japan. China’s position was clearly inappropriate with respect to the time and place. Still, we must look squarely at the factors that contributed to the lack of support for Japan’s proposal. The Japanese government’s call for a visit to the A-bombed cities, while it lies under the nuclear umbrella, lacks persuasiveness. If the call had been made by the A-bombed survivors, we could have seen a different development.

A regional effort to bring Northeast Asia, including Japan, closer to a nuclear-free zone and a decision to lead the movement seeking the global abolition of nuclear weapons--these are initiatives where Japan should step up and show resolve.

Among non-nuclear nations that have become impatient with the impasse over nuclear disarmament, the movement to create a nuclear weapons convention will likely continue to grow. Although such a trend might seem to be welcomed by Japan, in fact this nation is not a supporter of the movement. Can the Japanese people and the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki sway their government? The seriousness of residents of the A-bombed cities is being put to the test.

Keiko Nakamura

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1972. Received a graduate degree from the Monterey Institute of International Studies. After serving as the secretary-general of Peace Depot, an organization that makes recommendations on policies for a security framework not dependent on military force, she assumed her current position in 2012.

Haruko Moritaki, 76, co-chair of the Hiroshima Alliance for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (HANWA): Expand attention on all things nuclear

Mining and enriching uranium, working at nuclear power plants, developing and producing nuclear weapons; these things are not independent of each other, they are all related and together make up the “nuclear cycle.” At the same time, powerful interests are involved and intertwined. By focusing only on nuclear weapons themselves, it is difficult to realize their elimination.

The nuclear cycle is also a cycle that leads to damage from radiation. Depleted uranium weapons which are built from the remains of uranium enriched to create nuclear arms and nuclear fuel have caused serious internal exposure to people in Iraq and U.S. soldiers who returned from there following the Persian Gulf War. Also, in connection with uranium mines in India, the mine workers and the local residents are suffering health problems.

In Japan, too, a nuclear meltdown occurred at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. We, the citizens of Hiroshima, should expand our interest in all things nuclear on a much greater scale.

After the nuclear meltdown, renewed light was shed on the words “complete rejection of all uses of the atom, including nuclear power” and “the human race cannot coexist with nuclear weapons or nuclear power,” which were stated by my father (the late Ichiro Moritaki, then professor emeritus of Hiroshima University). He devoted his life to the movement against A- and H-bombs.

In the 1950s, my father did support the peaceful use of nuclear energy. However, as he learned about the reality of nuclear power generation and nuclear tests which were being conducted around the world, his anguish as a philosopher grew. After a critical look at his acceptance of nuclear power, he eventually arrived at a state of mind encapsulated by the words above.

Japan is now seeking to resume operations at the nation’s nuclear power plants as if we never experienced a nuclear meltdown. How seriously has Japan taken that nuclear catastrophe which took place in a country which had already suffered two nuclear bombings? How much soul-searching has it really done?

This autumn, the World Nuclear Victims Forum will be held in Hiroshima. People living in and around nuclear test sites and nuclear mines are invited to share their experiences. I’d like this to be an opportunity for us all to reflect on this disastrous nuclear damage as our own problem. If this can happen, the appeal from Hiroshima and Nagasaki could grow more universally persuasive.

Haruko Moritaki

Born in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, in 1939. She has been engaged in efforts to bring youth from India and Pakistan to Hiroshima and confront issues involving depleted uranium weapons. She is a member of the steering committee of the International Coalition to Ban Uranium Weapons (ICBUW).

--------------------

Until the very last nuclear weapon is gone

The worst, most inhumane weapons in human history were dropped above the heads of the A-bomb survivors, who have spoken out about their experiences to people around the world, exposing the scars that were seared onto their bodies and into their memories. Although almost 70 years have passed since then, a great number of nuclear weapons still exist in the world today.

The damage caused by the atomic bombs is not a thing of the past, but a fear that lingers to this very moment. This has been the appeal of the A-bomb survivors. And it is this appeal that has fueled recent global momentum for abolishing nuclear weapons from the perspective of their inhumanity. Since 2013, three international conferences have been held in Norway, Mexico, and Austria, where government representatives have discussed the potential consequences if nuclear weapons are used.

This possibility is considerably higher than people think and current momentum for nuclear abolition stems from such recognition. There are a variety of scenarios where a nuclear weapon could detonate, including the result of human error or negligent action; the theft of a nuclear weapon by terrorists or a cyberattack on a nuclear missile base; and a sudden nuclear strike in the midst of conflict. The current state of affairs, in terms of the possibility that nuclear weapons could be used, is considered more serious than a nuclear war scenario involving the nuclear superpowers at the time of the Cold War.

Of the nuclear warheads now held by the United States and Russia, about 2,000 from each country could be launched within just a few minutes following a presidential order. Meanwhile, India and Pakistan are targeting one another with nuclear weapons as a consequence of territorial disputes. Whatever the trigger, another Hiroshima and Nagasaki nightmare would be created if a nuclear weapon is ever used again.

“As long as even a single nuclear bomb or warhead exists, the possibility that nuclear weapons will be used one day remains.” This statement by Terumi Tanaka, the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), is not groundless fear-mongering. For this reason, the “non-use” of nuclear arms is not enough. These weapons must be eliminated.

Brad Roberts, a former senior official of the U.S. Department of Defense who oversaw the Obama administration’s nuclear strategy policy known as the “Nuclear Posture Review,” says that, in terms of the total deterrent capability, the role of nuclear weapons has become smaller. His remarks, however, do not square with the goal of total nuclear abolition.

Sugio Takahashi, the chief officer of the National Institute for Defense Studies, located in Tokyo, explains that deterrence under the current Japan-U.S. alliance is “like an onion.” This means that the surface is robustly covered with conventional weapons and a missile defense system which can be employed in actual warfare with less reluctance than using nuclear weapons. However, for situations where the skin of the “deterrent capability” is removed, powerful nuclear weapon are poised at the core.

On one hand, conventional forces dominate, both in quantity and quality, while on the other, nuclear forces are reduced in number, but are modernized and made more sophisticated. “As the portion of conventional forces grows larger, Japan should take on bigger roles. This is the U.S. view,” said Hirofumi Tosaki, a senior research fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs. The administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who promised the enactment of new security bills in his address before the U.S. Congress prior to their passage in the Japanese Diet, seems to act in accordance with the desires of the United States.

A spiral of mistrust cannot be controlled by weapons under the guise of deterrence. The appeal of the A-bomb survivors that “Neither nuclear weapons nor war must be allowed” has once again grown more persuasive.

With respect to the stability of the region surrounding Japan, current conditions in Northeast Asia must be faced squarely. Although China has declared a policy of “no first use” of nuclear weapons, it is steadily building up its nuclear capability. North Korea is pushing forward with its nuclear development program in order to defend its regime at all costs.

However high and thick the barriers are, to overcome them Japan must leave the nuclear umbrella and strive for the diplomatic denuclearization of Northeast Asia. Japan must work to advance both the local goal of creating a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the region by eliminating all nuclear weapons, and the global goal of realizing a nuclear weapons convention. But the first step is moving Japan’s politicians to act. Hiroshima and her citizens will continue to appeal for action until the day when the very last nuclear weapon is removed from this earth.

--------------------

Interview with Terumi Tanaka, secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo): Make nuclear weapons a legal and moral stigma What do A-bomb survivors who have been appealing for the need to abolish nuclear arms, based on their experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, think about the continuing existence of nuclear weapons in the world? The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Terumi Tanaka, 83, the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo).

What are your thoughts regarding the current global state of affairs involving nuclear abolition?

I took part in the NPT Review Conference in New York in April and talked about my experiences of the atomic bombing there. I met some of the government representatives of nuclear weapon states in person and made an appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Some diplomats listened to my story with tears in their eyes.

I believe that these tears are heartfelt. However, as soon as the topic of the conversation shifted to their national security policies, their attitude changed completely. The French representative went so far as to say that the French people take pride in the fact that their country possesses nuclear weapons.

It’s incredible that a remark like this was made to an A-bomb survivor, isn’t it?

Among the five nations which have been permitted to possess nuclear weapons, there are tensions between both the United States and Russia, and the United States and China. However, in defending their “privilege” to possess nuclear weapons, it’s obvious that they are strongly united. I came away from the conference feeling that the hurdle to overcome is very high.

Possessing and depending on such inhumane weapons of mass destruction, which have caused us such tremendous suffering, is an utter disgrace, not a privilege or a point of pride. What is needed is international opinion that the possession of nuclear weapons is nothing more than a legal and moral stigma. We must create a nuclear weapons convention in order to make them illegal.

The appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons, by highlighting their inhumanity, has gathered momentum. What are your hopes for this trend?

This trend has been strengthened mainly by non-nuclear nations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). At the NPT Review Conference, Austria and other countries that are actively seeking the abolition of nuclear weapons released a joint statement which drew the support of more than 150 nations. The A-bomb survivors are greatly encouraged by this, because the “inhumanity” of these weapons is exactly what we have been insisting for so long.

Do you think the Japanese government is responsive to the A-bomb survivors’ appeal?

The government’s response will be limited as long as it maintains a security policy which relies on U.S. nuclear weapons. I have the same message for every country: The A-bomb survivors can wait no longer. I urge not only the nuclear powers, but also those nations which rely on an ally’s nuclear umbrella, to move past nuclear deterrence. It goes without saying Japan is one of those latter nations.

If the Japanese government would squarely face the effects and the suffering the atomic bombings have caused to its people, without downplaying them, I don’t think they would ever be able to say, “We still need nuclear weapons.” The government’s failure to do this is reflected in its stance of adamantly rejecting the applications for A-bomb disease certification made by A-bomb survivors, who contend that their illnesses are a direct result of the atomic bombings.

How can we spread the appeals made by the A-bomb survivors to the world?

The nuclear weapon states say that they won’t use the nuclear weapons they possess, while the countries huddling under the nuclear umbrella justify their reliance on these weapons. In this scenario, any nation can insist that they have the “right” to possess them, too.

As long as a single nuclear weapon exists, it could be used one day. We hope that no one will ever suffer as we did. This is why the aging A-bomb survivors have appealed for all nuclear weapons to be abolished while we’re still alive. If we face difficulties, we must deepen our ties with countries and people worldwide that are dedicated to nuclear abolition, and urge every nation to take action to advance the elimination of nuclear arms. We will never give up on this goal.

Terumi Tanaka

Born in the former Manchuria (in northeastern China) in 1932. While a first-year student at Nagasaki Prefectural Nagasaki Junior High School, he experienced the atomic bombing while at his home, 3.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. Five members of his family, including his grandfather, were killed. He was formerly an associate professor at the school of engineering at Tohoku University. In June 2000, Mr. Tanaka became the secretary general of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations for the second time. He lives in Niiza, Saitama Prefecture.

(Originally published on June 21, 2015)