Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Survey of high school students in Hiroshima, Tokyo, New York on A-bombings

Jul. 2, 2015

by Masakazu Domen, Yumi Kanazaki, and Keiichiro Yamamoto, Staff Writers

A survey has been carried out on the current views of high school students in Japan and the United States 70 years after the atomic bombings. Questionnaires were distributed at Motomachi High School in Hiroshima, Hosei University Senior High School in Tokyo, and Stuyvesant High School in New York, all of which are known for their programs in peace studies. The results show differences between today’s teens and the generation of A-bomb survivors, as well as between Japan and the United States in attitudes toward the atomic bombings and the need for nuclear deterrence. At the same time, the students in all three locations take the survivors’ accounts seriously and are seeking to promote peace in the world.

On nuclear weapons: Supporting nuclear abolition after listening to survivors’ accounts first-hand As the A-bomb survivors age, the number of those who are able to share their account is declining, and the valuable chance for the younger generations to hear these stories first-hand is shrinking. The percentages of respondents who have listened to the experiences of A-bomb survivors directly were 69.7 percent in total: 90.6 percent at Motomachi, 66.5 percent at Hosei, and 31.4 percent at Stuyvesant.

Students were asked how they heard these accounts and could choose more than one answer. At Motomachi, more than 90 percent of the respondents chose “As part of a school activity.” Since most of the students at the high school were born and have been raised in and around the city of Hiroshima, 17.7 percent of the respondents have listened to A-bomb accounts first-hand from relatives. At Hosei, 80 percent chose “On a school trip.” Many of these students went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki on a school trip when they were attending its affiliated junior high school.

Survivors have shared their accounts at Stuyvesant High School, organized by the Japan Society, a New York-based organization that seeks to deepen mutual understanding between Japan and the U.S. More than 80 percent of the respondents at the high school chose “As part of a school activity.” “At a gathering I took part in” was chosen by 22.2 percent of the students, which is larger than the 7.6 percent of students at Motomachi or the 1.3 percent of students at Hosei. In social circumstances which differ from those in Japan, the American students are more active than passive.

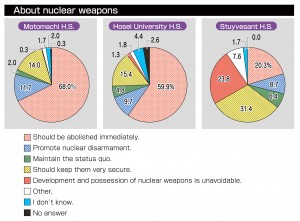

There is an interesting relationship between the ratios of those who have listened to survivors’ accounts directly and the responses to a certain question. Students were asked to select from seven choices regarding how they feel about nuclear weapons. “They must be abolished immediately” was chosen by 68.0 percent at Motomachi, 59.9 at Hosei, and 20.3 at Stuyvesant. These ratios are nearly the same as the percentages of students who have listened directly to survivors’ accounts.

A question on the date and time the atomic bombs were dropped revealed significant differences in the percentages of correct responses. Motomachi had the highest ratio of correct answers, followed by Hosei and Stuyvesant.

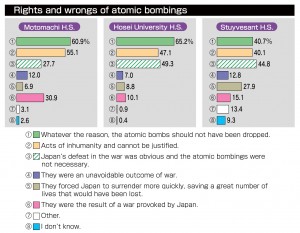

What differences can be seen between these teenagers and A-bomb survivors in their feelings about the atomic bombings? The strongest choice, “Whatever the reason, the atomic bombs should not have been dropped,” was favored by 57.5 percent of the high school students surveyed. (Respondents could choose up to three answers.) In comparison, 73.7 percent of Japanese survivors and 69.2 percent of survivors living abroad selected this answer.

Still, this answer was chosen by the largest number of respondents, followed by “They were acts of inhumanity and cannot be justified” (49.3 percent) and “Japan’s defeat in the war was obvious and the atomic bombings were not necessary” (38.2 percent). The order of the top three answers was the same in the survey of survivors.

Looking at each of the three schools, the difference in perspective between Japan and the U.S. becomes clear. At Stuyvesant High School, 27.9 percent of the students surveyed chose “They forced Japan to surrender more quickly, saving a great number of lives that would have been lost if the United States had invaded mainland Japan.” Less than 10 percent of the students at the two Japanese high schools chose this answer. Since this view is held by the general public in the U.S., and students could select up to three answers, this relatively low ratio of less than 30 percent may reflect a changing view among the younger generation.

The atomic bombings are sometimes referred to as retribution for the Pearl Harbor attack. However, “They were the result of a war provoked by Japan” was chosen by 15.1 percent of students at Stuyvesant, compared with 30.9 percent at Motomachi. At Hosei, the percentage was 10.1.

To the question “Should the president of the United States apologize for the atomic bombings?,” 24.4 percent of students at Stuyvesant chose “No, the president need not apologize.” This was slightly higher than the 20.3 percent which said “Yes, the president should apologize.” It is notable that about 20 percent of the American students expressed the opinion that the president should apologize. Both at Motomachi and Hosei, the great majority of students chose “Apart from the question of apologizing, the president should make efforts to abolish nuclear weapons.”

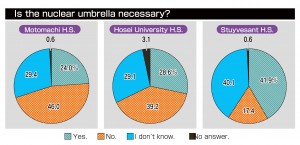

In the near future, high school students will take part in the policy-making process of their nations as voters. To the direct question “Do you think it is necessary for the United States to maintain the status quo and its nuclear arsenal to assure the security of its allies, including Japan?,” 37.4 percent of all high school respondents answered “No,” while 29.5 percent answered “Yes.”

When asked a similar question, 32.8 percent of the Japanese A-bomb survivors surveyed answered “No” and 22.9 percent said “Yes,” showing a similar trend. The international community has become increasingly aware of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and is seeking a way to ensure security without relying on nuclear deterrence. On the other hand, Japan and the U.S. are involved in tense international conditions in Northeast Asia. These results seem to reflect the dilemma felt by both teenagers and survivors.

By school, “Yes” was chosen by a relatively high 41.9 percent of the respondents at Stuyvesant. One student wrote, “Some nations will not comply with any rules set (regarding nuclear weapons). The U.S. should be in charge of maintaining a peaceful world.” At Hosei, 28.6 percent chose “Yes,” followed by 24.0 percent at Motomachi. The percentages of students who chose “No” came in the reverse order.

To the question “Do you think it is possible to abolish all nuclear weapons from the world in the not-too-distant future?,” 70.8 percent of all the respondents chose “No,” substantially exceeding the 8.5 percent of “Yes.” “No” was chosen by 86.0 percent at Stuyvesant, 68.7 at Hosei and 64.6 at Motomachi. To the same question, 58.2 percent of Japanese survivors and 61.6 percent of survivors living abroad answered “No.” This shows that teenagers hold more pessimistic views on the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Asked “Do you think your government takes a serious approach to the abolition of nuclear weapons?,” a total of 46.6 percent of all the respondents answered either “I don’t think it is serious” or “It is rather insufficient.” This was larger than the 32.6 percent of the sum of “It takes a serious approach” and “It is insufficient, but still of merit.” The three high schools showed the same trend.

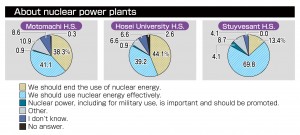

The threat posed by radiation has drawn increasing attention since the 2011 accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The same threat is posed by nuclear weapon. To a question about nuclear energy, 34.3 percent of all the respondents answered “We should end the use of nuclear energy.” But 47.1 percent chose “We should use nuclear energy effectively for peace.”

Hosei had the highest percentage (44.1) of respondents who support breaking away from the use of nuclear energy, followed by Motomachi (38.3) and Stuyvesant (13.4). It appears that the percentages reflect the distances of the schools from Fukushima. At Stuyvesant, 70 percent of the students indicated support for the effective use of nuclear energy.

One of the choices to the question “What should be done to promote the abolition of nuclear weapons?” was “Highlight the harm caused by radiation from nuclear tests and nuclear accidents, and strengthen the movement to end the use of nuclear energy.” The three high schools showed a notable difference in their answers to this question. Respondents were allowed to choose up to three answers. At Stuyvesant, 48.8 percent made this choice, and 22.9 at Hosei, but only 14.6 at Motomachi. This shows that nuclear weapons alone tend to attract people’s attention in Hiroshima.

--------------------

At the end of the questionnaire, the students were asked to write freely about what they have done to express their opposition to nuclear weapons or war, or what they think they should do to help create a peaceful world. Below are excerpts from their comments.

Motomachi High School: Create peace around ourselves

■We should look squarely at what’s happening around us. If there is bullying, we should not overlook it.

■I don’t think the nuclear weapon states will easily get rid of their nuclear arsenals. It’s important to prevent them from using their nuclear weapons. Hiroshima should call on the leaders of nations around the world to take action. I want to convey my views as a high school student.

■When I moved to an elementary school in the Kanto area (around Tokyo), I was surprised by how little people know about war or nuclear weapons. I realized that students aren’t involved in peace studies in other prefectures. At the same time, I found that I didn’t really know about Nagasaki. I want to study about Nagasaki and visit that city.

■I don’t know what to do to help realize peace. I don’t think that the elimination of nuclear weapons would bring peace.

■We shouldn’t get into quarrels and we should respect the people around us. We should get along with our friends.

■If we want to get rid of all the nuclear weapons from the entire world, the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council have to abolish their nuclear weapons first. Countries like the United States attack other nations suspected of possessing such weapons, as if they’re trying to eliminate their enemies.

■I like painting, so I want to paint pictures to express opposition to war.

■I hope to become a teacher. As a teacher from Hiroshima, I will convey the importance of peace to students in other prefectures, too.

■We can’t stop handing down the horrors of the atomic bombings. Listen to the survivors and share what you hear with the next generation. People must think about what they can do to prevent nuclear war from occurring and bring about lasting peace in the world.

■I want to learn more about the wars Japan has waged. I want to know more about what Japan did to other countries as well as the suffering that Japan has experienced.

■I always offer a silent prayer on the anniversary of the atomic bombing. I will continue doing this if I leave Hiroshima in the future and I’ll never forget about the atomic bombing.

■The current Japanese government seems to be edging closer to war. Politicians have no qualms about talking about waging war, because they don’t actually have to fight. To stop this, every person must have a logical argument against war.

■We must create peace in our own backyard. Don’t pass by people in need. If we all adopt this attitude in our interactions with others, peace can be realized. It’s the same thing between countries.

■When I go to college, I’ll meet many people from different parts of the country. If they don’t know about the atomic bombing, I’ll tell them. I won’t forget what I heard from my grandparents, and I’ll share their A-bomb experiences with my children and grandchildren and their generations.

■Learn more about others. Otherwise, no matter what we say to other people, we won’t be able to prevent conflicts from breaking out.

■I plan to make use of the English language skills I’ve been working on so I’ll be able to talk about Hiroshima outside of Japan.

Hosei University Senior High School: Learn about the suffering that Japan inflicted

■We have to know about what’s going on in the world and consider why these things are happening. Japan is not at war today, but we must be aware that war isn’t someone else’s affair.

■When a pebble is thrown into a pond, it makes ripples. The ripples may be small at first, but they become big waves and reach the opposite shore. We should throw a pebble in the hopes of raising people’s awareness of peace.

■We should focus on how to abolish nuclear weapons rather than how terrible they are.

■We should learn about war and peace and give thought to these issues to form our own opinions. We should focus on the present and future rather than the past.

■Recent weapons, including nuclear weapons, enable people to kill others without facing the victims. This undermines people’s respect for the dignity of others.

■I folded paper cranes with a wish for peace. On the anniversary of the end of the war, I talk with my family about war and peace.

■Conveying the A-bomb experiences at international conferences and conveying the cruel nature of these weapons will lead to peace.

■Japan’s war survivors are aging. Our generation must learn about the reality of war and pass their memories down to the next generation.

■Japan suffered the A-bomb attacks, but we must learn about the background that led up to the bombings and the damage Japan inflicted on other countries.

■It’s important that each and every one of us raise our voice against nuclear weapons.

■People in America may think that the war ended sooner because the atomic bombs were used. But the fact that many innocent people became victims is not so well known. This information should be included in school books all over the world.

■We should appeal to the world about how inhumane nuclear weapons are, and they should be eliminated along with nuclear power plants.

■I want to be a Self-Defense Force officer. Japan needs to be stronger to be able to defend itself.

■I have been to Hiroshima to learn about the atomic bombing. It’s important to actually go to the city that experienced the bombing to learn about it.

■Because we are the last generation that can listen first-hand to the A-bomb survivors talk about their experiences, I will tell what I learned on my school trip to the next generation. I will tell what happened and what I thought.

Stuyvesant High School: War can be necessary

■They shouldn’t have dropped the bomb on Nagasaki such a short time after dropping one on Hiroshima.

■My friend said that the U.S. decided to drop the A-bombs to end the war as quickly as possible. I vehemently disagreed and explained why the dropping of the A-bombs was wrong technically and ethically. He is another person who now opposes nuclear weapons.

■I think the simplest thing we could do is communicate with our local communities. If a community gets involved in a cause, then it may be taken to a city leader, then a state leader, and perhaps finally reach a federal level.

■I’d like to travel around the world to meet different people and share ideas with them. In order to create a more peaceful world, we need to accept our differences and embrace them.

■If possible, I want to go to Japan and express my apology to them, even if I wasn’t part of the war.

■After you fight a war, the side that comes out victorious isn’t necessarily the side that’s “right.” Rather, it’s just the side that’s “stronger.” War dehumanizes those who are forced to fight in it.

■In school textbooks, the harshness of war is often removed and filtered. People should know about the reality of the past and spread awareness so that the same mistakes will not be repeated.

■Even though we all strive for peace, war is inevitable if the ones involved cannot reach a compromise. We should be promoting peaceful compromise in order to strive for a more peaceful world.

■I was against war when I was younger, but now I think that war can be necessary. Say if Russia invades its neighbors, the U.S. and other world powers would have to take action.

■We should stop the glorification of war. Instead of focusing on the spoils the winner receives, we should instead show the bloodshed and violence, along with the lives and families ruined.

■I think that nuclear weapons are very dangerous and one weapon could wipe out an entire city. But nuclear abolition is going a step too far.

■Countries should own up to their crimes, especially committed during wartime, and teach about these atrocities to children in history classes so these actions aren’t repeated.

■I have devoted myself to studying about nuclear proliferation. Through my research, I have come to believe that all nuclear weapons should be banned because they are extremely dangerous.

■I think that a greater awareness of the effects of the bombs on the survivors and their descendents would create greater change, so use the Internet to spread their accounts. This should also be taught in school.

■In order to abolish nuclear weapons, someone has to set an example and do away with their own nuclear weapons before they have the right to ask other countries to get rid of theirs.

■To start, people should be aware of what war really is. There are people in the world who glorify war without fully understanding the casualties and sacrifices.

■Although some measures can prevent more nations from creating nuclear weapons, it is inevitable that some nations will not comply with any rules that are set. Certain nations, such as the U.S., should be in charge of maintaining a peaceful world.

■Nuclear weapons are unnecessary. They indiscriminately cause harm even to innocent people. Conventional weapons such as guns are already harmful enough.

■In history class, when people talk about the necessity of dropping the atomic bombs on Japan, I try to express disagreement and back this up with what I learned in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

■War will always be a part of civilization.

■Vote for people with similar beliefs as me for leadership positions. Discuss these issues with family and friends. Take part in a protest against nuclear weapons and war. Advocate for truthful government with no political propaganda.

--------------------

Interview with Tomoko Watanabe, executive director of ANT-Hiroshima

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Tomoko Watanabe, the executive director of ANT-Hiroshima, a local NPO, about what can be learned from the results of the survey. Ms. Watanabe is an expert in peace studies.

What is your general view of the results?

Students from three high schools in different locations are aware of the importance of listening to survivors’ accounts and the connection to Hiroshima. I felt the students’ sincere attitudes in trying to express their thoughts for peace. I also can see the important role of education in nurturing children’s abilities to form their own opinions by looking at history from various viewpoints.

Can you give an example?

One is the question about the date and time of the atomic bombing. It’s natural that a large number of students in Hiroshima can answer this question correctly. But we shouldn’t be overly optimistic and believe that this high percentage of correct answers is based on a deep interest and understanding of modern history including World War II.

What if we asked the same question about the attack on Pearl Harbor, which most Americans will be familiar with? How about the date on which the battle in Okinawa ended or the end of World War II? Also, it seems not many children in Hiroshima know the precise time the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

There is a difference between Japan and the U.S. in the students’ feelings about the atomic bombings.

Students in the U.S. are taught in school that there are various views and arguments with regard to the atomic bombings. Then they formulate their own ideas through discussion. I can see this in their comments, though they aren’t fully aware of the damage that was inflicted by the bombings.

On the other hand, the Japanese students are saying that war should not be fought based on the limited knowledge they obtained through listening to survivors and visiting the A-bomb museum. Many Americans still believe that the atomic bombings saved the lives of one million people that would have been lost in the event of a ground battle on Japan’s mainland. Students in Japan may not even be aware of such a view.

More than 20 percent of the American students surveyed expressed the view that their president should apologize for the atomic bombings. The ratio is higher than that of Japanese students. How do you interpret this?

It is an American tradition to place a high value on justice, clarify where responsibility lies, and express one’s ideas with a clear yes or no. This reflects the students’ cultural and religious background. Many of the choices favored by the Japanese students invoke Japanese ambiguity. At the same time, this is similar to the attitudes of A-bomb survivors, who buried their old hatreds to pursue the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Awareness and action on the part of young people are the keys to a peaceful world. How do you view the students’ comments?

The Japanese students are giving serious thought to the issues of war and peace. But, compared to the American students, they’re not as strongly committed to taking action and making appeals to society. It concerns me that they tend to focus only on the small world around them, saying they won’t bully others or they’ll be kind to others.

However, once they have a chance to broaden their horizons, this gap is immediately narrowed. One Hiroshima student wrote about living outside of Hiroshima and discovering that people don’t really know much about the atomic bombings. I see great potential in the students’ comments. I hope they will actively address the issues of nuclear weapons and peace with knowledge, which they can obtain through history classes and other avenues, and sensitivity, which they will develop through interacting with A-bomb survivors.

Profile

Tomoko Watanabe

Born in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, in 1953. Graduate of Hiroshima Shudo University. In 1989, she formed a group of Hiroshima citizens to promote friendship with the people of Asia. The group became the NPO ANT-Hiroshima (Asian Network of Trust) in 2007, and is engaged in providing education for international understanding and peace to citizens, children, and students from overseas. She has served in such roles as a member of the city’s board of education.

Questions and answers

(Numbers indicate percentages, except for questions that require written answers. Numbers were rounded to one decimal place, and do not always add up to 100. The total exceeds 100 in questions to which multiple answers were allowed.)

①Total (749)

②Motomachi (350)

③Hosei (227)

④Stuyvesant (172)

Do you know the date and time the United States dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Percentages of correct answers, date and time of Hiroshima bombing.

①52.6

②92.9

③26.4

④5.2

Percentages of correct answers, dates of Hiroshima, Nagasaki bombings.

①70.1

②88.3

③85.0

④13.4

Percentages of correct answers, dates and time of Hiroshima, Nagasaki bombings.

①26.3

②48.6

③10.6

④1.7

Have you heard accounts of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima or Nagasaki directly from an A-bomb survivor?

Yes.

①69.7

②90.6

③66.5

④31.4

No.

①29.9

②9.4

③33.0

④67.4

No answer.

①0.4

②0.0

③0.4

④1.2

(If you answered “Yes”) Under what circumstances did you hear the A-bomb account? (Circle all that apply.)

From my grandparent or relative who is an A-bomb survivor.

①11.9

②17.7

③4.0

④0.0

As part of a school activity.

①76.8

②93.4

③39.7

④83.3

On a school trip to Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

①30.8

②12.0

③81.5

④0.0

At a gathering that I took part in.

①7.3

②7.6

③1.3

④22.2

Other

①3.1

②2.8

③0.0

④13.0

Have you seen or heard recordings of A-bomb accounts, or read any A-bomb accounts? (With the exception of descriptions in a textbook or short news items in the media) If so, in what ways have you learned about the atomic bombings? (Circle all that apply.)

I saw footage or heard an audio recording of an A-bomb survivor’s account.

①50.6

②48.0

③50.2

④56.4

I read the account of an A-bomb survivor.

①25.5

②18.6

③18.9

④48.3

I saw a picture made by an A-bomb survivor which depicts memories of the atomic bombing.

①36.8

②44.0

③29.5

④32.0

I looked at a book of photographs which has information about A-bomb survivors or A-bombed areas.

①39.4

②40.6

③37.4

④39.5

I learned about the atomic bombings through comic books, literature, or movies.

①60.5

②64.3

③55.9

④58.7

I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum or the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

①60.1

②88.6

③59.0

④3.5

Other.

①2.1

②2.3

③0.0

④4.7

Not applicable.

①4.9

②0.9

③8.8

④8.1

What are your feelings about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? (Circle up to three answers.)

Whatever the reason, the atomic bombs should not have been dropped.

①57.5

②60.9

③65.2

④40.7

They were acts of inhumanity and cannot be justified.

①49.3

②55.1

③47.1

④40.1

Japan’s defeat in the war was obvious and the atomic bombings were not necessary.

①38.2

②27.7

③49.3

④44.8

They were an unavoidable outcome of war.

①10.7

②12.0

③7.0

④12.8

They forced Japan to surrender more quickly, saving a great number of lives that would have been lost if the United States had invaded mainland Japan.

①12.3

②6.9

③8.8

④27.9

They were the result of a war provoked by Japan.

①21.0

②30.9

③10.1

④15.1

Other.

①4.8

②3.1

③0.9

④13.4

I don’t know.

①3.5

②2.6

③0.4

④9.3

Should the president of the United States apologize for the atomic bombings? (Circle one answer.)

Yes, the president should apologize.

①10.4

②9.1

③4.8

④20.3

No, the president need not apologize.

①13.0

②9.1

③10.1

④24.4

Apart from the question of apologizing, the president should make efforts to abolish nuclear weapons.

①68.4

②77.1

③77.5

④38.4

Other.

①2.4

②1.1

③0.9

④7.0

I don’t know.

①4.8

②2.9

③4.0

④9.9

No answer.

①1.1

②0.6

③2.6

④0.0

What are your feelings about nuclear weapons? (Circle one answer.)

They are extremely inhumane weapons and should be abolished immediately.

①54.6

②68.0

③59.9

④20.3

The five nuclear weapon states established by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Treaty (NPT)--the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China--should be permitted to possess them and promote nuclear disarmament.

①10.4

②11.7

③9.7

④8.7

I prefer the status quo because, under these conditions, a nuclear war has been avoided.

①3.9

②2.0

③4.8

④20.3

We should be extremely wary of the danger that nuclear weapons may fall into the hands of terrorists and we should keep them very secure.

①18.4

②14.0

③15.4

④31.4

The fact that countries will develop and possess nuclear weapons to defend themselves is unavoidable.

①6.0

②0.3

③1.3

④23.8

Other.

①3.1

②1.7

③1.8

④7.6

I don’t know.

①2.7

②2.0

③4.4

④1.7

No answer.

①0.9

②0.3

③2.6

④0.0

What are your feelings about nuclear power plants? (Circle one answer.)

We should end the use of nuclear energy because nuclear power plants can be dangerous, too, like nuclear weapons.

①34.3

②38.3

③44.1

④13.4

We should use nuclear energy effectively, “for peace,” which is different from nuclear weapons.

①47.1

②41.1

③39.2

④69.8

Nuclear power, including for military use, is important and should be promoted.

①1.6

②0.9

③0.9

④4.1

Other.

①9.1

②10.9

③6.6

④8.7

I don’t know.

①6.9

②8.6

③6.6

④4.1

No answer.

①0.9

②0.3

③2.6

④0.0

Do you think it is necessary for the United States to maintain the status quo and its nuclear arsenal to assure the security of its allies, including Japan?

Yes.

①29.5

②24.0

③28.6

④41.9

No.

①37.4

②46.0

③39.2

④17.4

I don’t know.

①31.8

②29.4

③29.1

④40.1

No answer.

①1.3

②0.6

③3.1

④0.6

Do you think it is possible to abolish all nuclear weapons from the world in the not-too-distant future? (Circle one answer.)

Yes.

①8.5

②10.0

③6.6

④8.1

No.

①70.8

②64.6

③68.7

④86.0

I don’t know.

①19.8

②25.4

③21.6

④5.8

No answer.

①0.9

②0.0

③3.1

④0.0

Do you think your government takes a serious approach to the abolition of nuclear weapons?

It takes a serious approach.

①6.7

②8.0

③6.2

④4.7

It is insufficient, but still of merit.

①25.9

②31.1

③15.4

④29.1

It is rather insufficient.

①31.4

②34.0

③32.6

④24.4

I don’t think it is serious.

①15.2

②12.9

③17.6

④16.9

I don’t know.

①20.7

②14.0

③27.8

④25.0

No answer.

①0.1

②0.0

③0.4

④0.0

Do you think the accounts of the A-bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have helped prevent the use of nuclear weapons and advance peace in the world?

Yes.

①36.4

②45.1

③40.5

④13.4

Yes, to some extent.

①49.8

②46.9

③47.6

④58.7

I don’t really think so.

①7.6

②4.3

③6.6

④15.7

No.

①1.7

②0.6

③1.3

④4.7

I don’t know.

①3.5

②1.7

③3.1

④7.6

No answer.

①0.9

②1.4

③0.9

④0.0

Do you think the reality of the damage caused by the atomic bombings is widely known in your country?

It is widely known.

①9.7

②5.7

③12.8

④14.0

It is known to some extent.

①46.3

②42.9

③50.7

④47.7

It is not widely known.

①33.9

②39.1

③28.2

④30.8

Few people know about it.

①7.3

②9.7

③4.8

④5.8

I don’t know.

①2.5

②2.6

③3.1

④1.7

No answer.

①0.1

②0.0

③0.4

④0.0

How can the A-bomb survivors convey their accounts to the world more widely and what should be done to promote the abolition of nuclear weapons? (Circle up to three answers.)

Focus on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and make efforts to convey this to the international community.

①62.3

②61.4

③60.4

④66.9

Press the Japanese government to play a leadership role at the United Nations and at international conferences.

①25.4

②27.7

③22.9

④23.8

Appeal to the U.S. government and the American public to motivate the United States to take stronger action.

①21.9

②20.6

③19.8

④27.3

The Japanese people should face up to the wartime atrocities they perpetrated in Asia and reconsider the nation’s current actions.

①17.6

②20.6

③16.3

④13.4

Turn our attention to the damage caused by war in other parts of the world and promote nuclear abolition by working with war victims.

①40.3

②41.7

③36.1

④43.0

Highlight the harm caused by radiation from nuclear tests and nuclear accidents, and strengthen the movement to end the use of nuclear energy.

①25.0

②14.6

③22.9

④48.8

Other.

①3.3

②2.9

③1.3

④7.0

I don’t know.

①4.8

②2.9

③7.0

④5.8

(Originally published on May 9, 2015)

Students in both nations acknowledge importance of survivors’ accounts

A survey has been carried out on the current views of high school students in Japan and the United States 70 years after the atomic bombings. Questionnaires were distributed at Motomachi High School in Hiroshima, Hosei University Senior High School in Tokyo, and Stuyvesant High School in New York, all of which are known for their programs in peace studies. The results show differences between today’s teens and the generation of A-bomb survivors, as well as between Japan and the United States in attitudes toward the atomic bombings and the need for nuclear deterrence. At the same time, the students in all three locations take the survivors’ accounts seriously and are seeking to promote peace in the world.

On nuclear weapons: Supporting nuclear abolition after listening to survivors’ accounts first-hand As the A-bomb survivors age, the number of those who are able to share their account is declining, and the valuable chance for the younger generations to hear these stories first-hand is shrinking. The percentages of respondents who have listened to the experiences of A-bomb survivors directly were 69.7 percent in total: 90.6 percent at Motomachi, 66.5 percent at Hosei, and 31.4 percent at Stuyvesant.

Students were asked how they heard these accounts and could choose more than one answer. At Motomachi, more than 90 percent of the respondents chose “As part of a school activity.” Since most of the students at the high school were born and have been raised in and around the city of Hiroshima, 17.7 percent of the respondents have listened to A-bomb accounts first-hand from relatives. At Hosei, 80 percent chose “On a school trip.” Many of these students went to Hiroshima and Nagasaki on a school trip when they were attending its affiliated junior high school.

Survivors have shared their accounts at Stuyvesant High School, organized by the Japan Society, a New York-based organization that seeks to deepen mutual understanding between Japan and the U.S. More than 80 percent of the respondents at the high school chose “As part of a school activity.” “At a gathering I took part in” was chosen by 22.2 percent of the students, which is larger than the 7.6 percent of students at Motomachi or the 1.3 percent of students at Hosei. In social circumstances which differ from those in Japan, the American students are more active than passive.

There is an interesting relationship between the ratios of those who have listened to survivors’ accounts directly and the responses to a certain question. Students were asked to select from seven choices regarding how they feel about nuclear weapons. “They must be abolished immediately” was chosen by 68.0 percent at Motomachi, 59.9 at Hosei, and 20.3 at Stuyvesant. These ratios are nearly the same as the percentages of students who have listened directly to survivors’ accounts.

A question on the date and time the atomic bombs were dropped revealed significant differences in the percentages of correct responses. Motomachi had the highest ratio of correct answers, followed by Hosei and Stuyvesant.

Whether the atomic bombings were right or wrong: 20% of U.S. students think the president should apologize

What differences can be seen between these teenagers and A-bomb survivors in their feelings about the atomic bombings? The strongest choice, “Whatever the reason, the atomic bombs should not have been dropped,” was favored by 57.5 percent of the high school students surveyed. (Respondents could choose up to three answers.) In comparison, 73.7 percent of Japanese survivors and 69.2 percent of survivors living abroad selected this answer.

Still, this answer was chosen by the largest number of respondents, followed by “They were acts of inhumanity and cannot be justified” (49.3 percent) and “Japan’s defeat in the war was obvious and the atomic bombings were not necessary” (38.2 percent). The order of the top three answers was the same in the survey of survivors.

Looking at each of the three schools, the difference in perspective between Japan and the U.S. becomes clear. At Stuyvesant High School, 27.9 percent of the students surveyed chose “They forced Japan to surrender more quickly, saving a great number of lives that would have been lost if the United States had invaded mainland Japan.” Less than 10 percent of the students at the two Japanese high schools chose this answer. Since this view is held by the general public in the U.S., and students could select up to three answers, this relatively low ratio of less than 30 percent may reflect a changing view among the younger generation.

The atomic bombings are sometimes referred to as retribution for the Pearl Harbor attack. However, “They were the result of a war provoked by Japan” was chosen by 15.1 percent of students at Stuyvesant, compared with 30.9 percent at Motomachi. At Hosei, the percentage was 10.1.

To the question “Should the president of the United States apologize for the atomic bombings?,” 24.4 percent of students at Stuyvesant chose “No, the president need not apologize.” This was slightly higher than the 20.3 percent which said “Yes, the president should apologize.” It is notable that about 20 percent of the American students expressed the opinion that the president should apologize. Both at Motomachi and Hosei, the great majority of students chose “Apart from the question of apologizing, the president should make efforts to abolish nuclear weapons.”

Is the nuclear umbrella necessary?: 29% approve, reflecting dilemma

In the near future, high school students will take part in the policy-making process of their nations as voters. To the direct question “Do you think it is necessary for the United States to maintain the status quo and its nuclear arsenal to assure the security of its allies, including Japan?,” 37.4 percent of all high school respondents answered “No,” while 29.5 percent answered “Yes.”

When asked a similar question, 32.8 percent of the Japanese A-bomb survivors surveyed answered “No” and 22.9 percent said “Yes,” showing a similar trend. The international community has become increasingly aware of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and is seeking a way to ensure security without relying on nuclear deterrence. On the other hand, Japan and the U.S. are involved in tense international conditions in Northeast Asia. These results seem to reflect the dilemma felt by both teenagers and survivors.

By school, “Yes” was chosen by a relatively high 41.9 percent of the respondents at Stuyvesant. One student wrote, “Some nations will not comply with any rules set (regarding nuclear weapons). The U.S. should be in charge of maintaining a peaceful world.” At Hosei, 28.6 percent chose “Yes,” followed by 24.0 percent at Motomachi. The percentages of students who chose “No” came in the reverse order.

To the question “Do you think it is possible to abolish all nuclear weapons from the world in the not-too-distant future?,” 70.8 percent of all the respondents chose “No,” substantially exceeding the 8.5 percent of “Yes.” “No” was chosen by 86.0 percent at Stuyvesant, 68.7 at Hosei and 64.6 at Motomachi. To the same question, 58.2 percent of Japanese survivors and 61.6 percent of survivors living abroad answered “No.” This shows that teenagers hold more pessimistic views on the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Asked “Do you think your government takes a serious approach to the abolition of nuclear weapons?,” a total of 46.6 percent of all the respondents answered either “I don’t think it is serious” or “It is rather insufficient.” This was larger than the 32.6 percent of the sum of “It takes a serious approach” and “It is insufficient, but still of merit.” The three high schools showed the same trend.

On nuclear energy: 47% support its effective use

The threat posed by radiation has drawn increasing attention since the 2011 accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The same threat is posed by nuclear weapon. To a question about nuclear energy, 34.3 percent of all the respondents answered “We should end the use of nuclear energy.” But 47.1 percent chose “We should use nuclear energy effectively for peace.”

Hosei had the highest percentage (44.1) of respondents who support breaking away from the use of nuclear energy, followed by Motomachi (38.3) and Stuyvesant (13.4). It appears that the percentages reflect the distances of the schools from Fukushima. At Stuyvesant, 70 percent of the students indicated support for the effective use of nuclear energy.

One of the choices to the question “What should be done to promote the abolition of nuclear weapons?” was “Highlight the harm caused by radiation from nuclear tests and nuclear accidents, and strengthen the movement to end the use of nuclear energy.” The three high schools showed a notable difference in their answers to this question. Respondents were allowed to choose up to three answers. At Stuyvesant, 48.8 percent made this choice, and 22.9 at Hosei, but only 14.6 at Motomachi. This shows that nuclear weapons alone tend to attract people’s attention in Hiroshima.

--------------------

Students’ comments

At the end of the questionnaire, the students were asked to write freely about what they have done to express their opposition to nuclear weapons or war, or what they think they should do to help create a peaceful world. Below are excerpts from their comments.

Motomachi High School: Create peace around ourselves

■We should look squarely at what’s happening around us. If there is bullying, we should not overlook it.

■I don’t think the nuclear weapon states will easily get rid of their nuclear arsenals. It’s important to prevent them from using their nuclear weapons. Hiroshima should call on the leaders of nations around the world to take action. I want to convey my views as a high school student.

■When I moved to an elementary school in the Kanto area (around Tokyo), I was surprised by how little people know about war or nuclear weapons. I realized that students aren’t involved in peace studies in other prefectures. At the same time, I found that I didn’t really know about Nagasaki. I want to study about Nagasaki and visit that city.

■I don’t know what to do to help realize peace. I don’t think that the elimination of nuclear weapons would bring peace.

■We shouldn’t get into quarrels and we should respect the people around us. We should get along with our friends.

■If we want to get rid of all the nuclear weapons from the entire world, the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council have to abolish their nuclear weapons first. Countries like the United States attack other nations suspected of possessing such weapons, as if they’re trying to eliminate their enemies.

■I like painting, so I want to paint pictures to express opposition to war.

■I hope to become a teacher. As a teacher from Hiroshima, I will convey the importance of peace to students in other prefectures, too.

■We can’t stop handing down the horrors of the atomic bombings. Listen to the survivors and share what you hear with the next generation. People must think about what they can do to prevent nuclear war from occurring and bring about lasting peace in the world.

■I want to learn more about the wars Japan has waged. I want to know more about what Japan did to other countries as well as the suffering that Japan has experienced.

■I always offer a silent prayer on the anniversary of the atomic bombing. I will continue doing this if I leave Hiroshima in the future and I’ll never forget about the atomic bombing.

■The current Japanese government seems to be edging closer to war. Politicians have no qualms about talking about waging war, because they don’t actually have to fight. To stop this, every person must have a logical argument against war.

■We must create peace in our own backyard. Don’t pass by people in need. If we all adopt this attitude in our interactions with others, peace can be realized. It’s the same thing between countries.

■When I go to college, I’ll meet many people from different parts of the country. If they don’t know about the atomic bombing, I’ll tell them. I won’t forget what I heard from my grandparents, and I’ll share their A-bomb experiences with my children and grandchildren and their generations.

■Learn more about others. Otherwise, no matter what we say to other people, we won’t be able to prevent conflicts from breaking out.

■I plan to make use of the English language skills I’ve been working on so I’ll be able to talk about Hiroshima outside of Japan.

Hosei University Senior High School: Learn about the suffering that Japan inflicted

■We have to know about what’s going on in the world and consider why these things are happening. Japan is not at war today, but we must be aware that war isn’t someone else’s affair.

■When a pebble is thrown into a pond, it makes ripples. The ripples may be small at first, but they become big waves and reach the opposite shore. We should throw a pebble in the hopes of raising people’s awareness of peace.

■We should focus on how to abolish nuclear weapons rather than how terrible they are.

■We should learn about war and peace and give thought to these issues to form our own opinions. We should focus on the present and future rather than the past.

■Recent weapons, including nuclear weapons, enable people to kill others without facing the victims. This undermines people’s respect for the dignity of others.

■I folded paper cranes with a wish for peace. On the anniversary of the end of the war, I talk with my family about war and peace.

■Conveying the A-bomb experiences at international conferences and conveying the cruel nature of these weapons will lead to peace.

■Japan’s war survivors are aging. Our generation must learn about the reality of war and pass their memories down to the next generation.

■Japan suffered the A-bomb attacks, but we must learn about the background that led up to the bombings and the damage Japan inflicted on other countries.

■It’s important that each and every one of us raise our voice against nuclear weapons.

■People in America may think that the war ended sooner because the atomic bombs were used. But the fact that many innocent people became victims is not so well known. This information should be included in school books all over the world.

■We should appeal to the world about how inhumane nuclear weapons are, and they should be eliminated along with nuclear power plants.

■I want to be a Self-Defense Force officer. Japan needs to be stronger to be able to defend itself.

■I have been to Hiroshima to learn about the atomic bombing. It’s important to actually go to the city that experienced the bombing to learn about it.

■Because we are the last generation that can listen first-hand to the A-bomb survivors talk about their experiences, I will tell what I learned on my school trip to the next generation. I will tell what happened and what I thought.

Stuyvesant High School: War can be necessary

■They shouldn’t have dropped the bomb on Nagasaki such a short time after dropping one on Hiroshima.

■My friend said that the U.S. decided to drop the A-bombs to end the war as quickly as possible. I vehemently disagreed and explained why the dropping of the A-bombs was wrong technically and ethically. He is another person who now opposes nuclear weapons.

■I think the simplest thing we could do is communicate with our local communities. If a community gets involved in a cause, then it may be taken to a city leader, then a state leader, and perhaps finally reach a federal level.

■I’d like to travel around the world to meet different people and share ideas with them. In order to create a more peaceful world, we need to accept our differences and embrace them.

■If possible, I want to go to Japan and express my apology to them, even if I wasn’t part of the war.

■After you fight a war, the side that comes out victorious isn’t necessarily the side that’s “right.” Rather, it’s just the side that’s “stronger.” War dehumanizes those who are forced to fight in it.

■In school textbooks, the harshness of war is often removed and filtered. People should know about the reality of the past and spread awareness so that the same mistakes will not be repeated.

■Even though we all strive for peace, war is inevitable if the ones involved cannot reach a compromise. We should be promoting peaceful compromise in order to strive for a more peaceful world.

■I was against war when I was younger, but now I think that war can be necessary. Say if Russia invades its neighbors, the U.S. and other world powers would have to take action.

■We should stop the glorification of war. Instead of focusing on the spoils the winner receives, we should instead show the bloodshed and violence, along with the lives and families ruined.

■I think that nuclear weapons are very dangerous and one weapon could wipe out an entire city. But nuclear abolition is going a step too far.

■Countries should own up to their crimes, especially committed during wartime, and teach about these atrocities to children in history classes so these actions aren’t repeated.

■I have devoted myself to studying about nuclear proliferation. Through my research, I have come to believe that all nuclear weapons should be banned because they are extremely dangerous.

■I think that a greater awareness of the effects of the bombs on the survivors and their descendents would create greater change, so use the Internet to spread their accounts. This should also be taught in school.

■In order to abolish nuclear weapons, someone has to set an example and do away with their own nuclear weapons before they have the right to ask other countries to get rid of theirs.

■To start, people should be aware of what war really is. There are people in the world who glorify war without fully understanding the casualties and sacrifices.

■Although some measures can prevent more nations from creating nuclear weapons, it is inevitable that some nations will not comply with any rules that are set. Certain nations, such as the U.S., should be in charge of maintaining a peaceful world.

■Nuclear weapons are unnecessary. They indiscriminately cause harm even to innocent people. Conventional weapons such as guns are already harmful enough.

■In history class, when people talk about the necessity of dropping the atomic bombs on Japan, I try to express disagreement and back this up with what I learned in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

■War will always be a part of civilization.

■Vote for people with similar beliefs as me for leadership positions. Discuss these issues with family and friends. Take part in a protest against nuclear weapons and war. Advocate for truthful government with no political propaganda.

--------------------

Education to broaden our perspective is important

Interview with Tomoko Watanabe, executive director of ANT-Hiroshima

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Tomoko Watanabe, the executive director of ANT-Hiroshima, a local NPO, about what can be learned from the results of the survey. Ms. Watanabe is an expert in peace studies.

What is your general view of the results?

Students from three high schools in different locations are aware of the importance of listening to survivors’ accounts and the connection to Hiroshima. I felt the students’ sincere attitudes in trying to express their thoughts for peace. I also can see the important role of education in nurturing children’s abilities to form their own opinions by looking at history from various viewpoints.

Can you give an example?

One is the question about the date and time of the atomic bombing. It’s natural that a large number of students in Hiroshima can answer this question correctly. But we shouldn’t be overly optimistic and believe that this high percentage of correct answers is based on a deep interest and understanding of modern history including World War II.

What if we asked the same question about the attack on Pearl Harbor, which most Americans will be familiar with? How about the date on which the battle in Okinawa ended or the end of World War II? Also, it seems not many children in Hiroshima know the precise time the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

There is a difference between Japan and the U.S. in the students’ feelings about the atomic bombings.

Students in the U.S. are taught in school that there are various views and arguments with regard to the atomic bombings. Then they formulate their own ideas through discussion. I can see this in their comments, though they aren’t fully aware of the damage that was inflicted by the bombings.

On the other hand, the Japanese students are saying that war should not be fought based on the limited knowledge they obtained through listening to survivors and visiting the A-bomb museum. Many Americans still believe that the atomic bombings saved the lives of one million people that would have been lost in the event of a ground battle on Japan’s mainland. Students in Japan may not even be aware of such a view.

More than 20 percent of the American students surveyed expressed the view that their president should apologize for the atomic bombings. The ratio is higher than that of Japanese students. How do you interpret this?

It is an American tradition to place a high value on justice, clarify where responsibility lies, and express one’s ideas with a clear yes or no. This reflects the students’ cultural and religious background. Many of the choices favored by the Japanese students invoke Japanese ambiguity. At the same time, this is similar to the attitudes of A-bomb survivors, who buried their old hatreds to pursue the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Awareness and action on the part of young people are the keys to a peaceful world. How do you view the students’ comments?

The Japanese students are giving serious thought to the issues of war and peace. But, compared to the American students, they’re not as strongly committed to taking action and making appeals to society. It concerns me that they tend to focus only on the small world around them, saying they won’t bully others or they’ll be kind to others.

However, once they have a chance to broaden their horizons, this gap is immediately narrowed. One Hiroshima student wrote about living outside of Hiroshima and discovering that people don’t really know much about the atomic bombings. I see great potential in the students’ comments. I hope they will actively address the issues of nuclear weapons and peace with knowledge, which they can obtain through history classes and other avenues, and sensitivity, which they will develop through interacting with A-bomb survivors.

Profile

Tomoko Watanabe

Born in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, in 1953. Graduate of Hiroshima Shudo University. In 1989, she formed a group of Hiroshima citizens to promote friendship with the people of Asia. The group became the NPO ANT-Hiroshima (Asian Network of Trust) in 2007, and is engaged in providing education for international understanding and peace to citizens, children, and students from overseas. She has served in such roles as a member of the city’s board of education.

Questions and answers

(Numbers indicate percentages, except for questions that require written answers. Numbers were rounded to one decimal place, and do not always add up to 100. The total exceeds 100 in questions to which multiple answers were allowed.)

①Total (749)

②Motomachi (350)

③Hosei (227)

④Stuyvesant (172)

Do you know the date and time the United States dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Percentages of correct answers, date and time of Hiroshima bombing.

①52.6

②92.9

③26.4

④5.2

Percentages of correct answers, dates of Hiroshima, Nagasaki bombings.

①70.1

②88.3

③85.0

④13.4

Percentages of correct answers, dates and time of Hiroshima, Nagasaki bombings.

①26.3

②48.6

③10.6

④1.7

Have you heard accounts of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima or Nagasaki directly from an A-bomb survivor?

Yes.

①69.7

②90.6

③66.5

④31.4

No.

①29.9

②9.4

③33.0

④67.4

No answer.

①0.4

②0.0

③0.4

④1.2

(If you answered “Yes”) Under what circumstances did you hear the A-bomb account? (Circle all that apply.)

From my grandparent or relative who is an A-bomb survivor.

①11.9

②17.7

③4.0

④0.0

As part of a school activity.

①76.8

②93.4

③39.7

④83.3

On a school trip to Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

①30.8

②12.0

③81.5

④0.0

At a gathering that I took part in.

①7.3

②7.6

③1.3

④22.2

Other

①3.1

②2.8

③0.0

④13.0

Have you seen or heard recordings of A-bomb accounts, or read any A-bomb accounts? (With the exception of descriptions in a textbook or short news items in the media) If so, in what ways have you learned about the atomic bombings? (Circle all that apply.)

I saw footage or heard an audio recording of an A-bomb survivor’s account.

①50.6

②48.0

③50.2

④56.4

I read the account of an A-bomb survivor.

①25.5

②18.6

③18.9

④48.3

I saw a picture made by an A-bomb survivor which depicts memories of the atomic bombing.

①36.8

②44.0

③29.5

④32.0

I looked at a book of photographs which has information about A-bomb survivors or A-bombed areas.

①39.4

②40.6

③37.4

④39.5

I learned about the atomic bombings through comic books, literature, or movies.

①60.5

②64.3

③55.9

④58.7

I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum or the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

①60.1

②88.6

③59.0

④3.5

Other.

①2.1

②2.3

③0.0

④4.7

Not applicable.

①4.9

②0.9

③8.8

④8.1

What are your feelings about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? (Circle up to three answers.)

Whatever the reason, the atomic bombs should not have been dropped.

①57.5

②60.9

③65.2

④40.7

They were acts of inhumanity and cannot be justified.

①49.3

②55.1

③47.1

④40.1

Japan’s defeat in the war was obvious and the atomic bombings were not necessary.

①38.2

②27.7

③49.3

④44.8

They were an unavoidable outcome of war.

①10.7

②12.0

③7.0

④12.8

They forced Japan to surrender more quickly, saving a great number of lives that would have been lost if the United States had invaded mainland Japan.

①12.3

②6.9

③8.8

④27.9

They were the result of a war provoked by Japan.

①21.0

②30.9

③10.1

④15.1

Other.

①4.8

②3.1

③0.9

④13.4

I don’t know.

①3.5

②2.6

③0.4

④9.3

Should the president of the United States apologize for the atomic bombings? (Circle one answer.)

Yes, the president should apologize.

①10.4

②9.1

③4.8

④20.3

No, the president need not apologize.

①13.0

②9.1

③10.1

④24.4

Apart from the question of apologizing, the president should make efforts to abolish nuclear weapons.

①68.4

②77.1

③77.5

④38.4

Other.

①2.4

②1.1

③0.9

④7.0

I don’t know.

①4.8

②2.9

③4.0

④9.9

No answer.

①1.1

②0.6

③2.6

④0.0

What are your feelings about nuclear weapons? (Circle one answer.)

They are extremely inhumane weapons and should be abolished immediately.

①54.6

②68.0

③59.9

④20.3

The five nuclear weapon states established by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Treaty (NPT)--the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China--should be permitted to possess them and promote nuclear disarmament.

①10.4

②11.7

③9.7

④8.7

I prefer the status quo because, under these conditions, a nuclear war has been avoided.

①3.9

②2.0

③4.8

④20.3

We should be extremely wary of the danger that nuclear weapons may fall into the hands of terrorists and we should keep them very secure.

①18.4

②14.0

③15.4

④31.4

The fact that countries will develop and possess nuclear weapons to defend themselves is unavoidable.

①6.0

②0.3

③1.3

④23.8

Other.

①3.1

②1.7

③1.8

④7.6

I don’t know.

①2.7

②2.0

③4.4

④1.7

No answer.

①0.9

②0.3

③2.6

④0.0

What are your feelings about nuclear power plants? (Circle one answer.)

We should end the use of nuclear energy because nuclear power plants can be dangerous, too, like nuclear weapons.

①34.3

②38.3

③44.1

④13.4

We should use nuclear energy effectively, “for peace,” which is different from nuclear weapons.

①47.1

②41.1

③39.2

④69.8

Nuclear power, including for military use, is important and should be promoted.

①1.6

②0.9

③0.9

④4.1

Other.

①9.1

②10.9

③6.6

④8.7

I don’t know.

①6.9

②8.6

③6.6

④4.1

No answer.

①0.9

②0.3

③2.6

④0.0

Do you think it is necessary for the United States to maintain the status quo and its nuclear arsenal to assure the security of its allies, including Japan?

Yes.

①29.5

②24.0

③28.6

④41.9

No.

①37.4

②46.0

③39.2

④17.4

I don’t know.

①31.8

②29.4

③29.1

④40.1

No answer.

①1.3

②0.6

③3.1

④0.6

Do you think it is possible to abolish all nuclear weapons from the world in the not-too-distant future? (Circle one answer.)

Yes.

①8.5

②10.0

③6.6

④8.1

No.

①70.8

②64.6

③68.7

④86.0

I don’t know.

①19.8

②25.4

③21.6

④5.8

No answer.

①0.9

②0.0

③3.1

④0.0

Do you think your government takes a serious approach to the abolition of nuclear weapons?

It takes a serious approach.

①6.7

②8.0

③6.2

④4.7

It is insufficient, but still of merit.

①25.9

②31.1

③15.4

④29.1

It is rather insufficient.

①31.4

②34.0

③32.6

④24.4

I don’t think it is serious.

①15.2

②12.9

③17.6

④16.9

I don’t know.

①20.7

②14.0

③27.8

④25.0

No answer.

①0.1

②0.0

③0.4

④0.0

Do you think the accounts of the A-bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have helped prevent the use of nuclear weapons and advance peace in the world?

Yes.

①36.4

②45.1

③40.5

④13.4

Yes, to some extent.

①49.8

②46.9

③47.6

④58.7

I don’t really think so.

①7.6

②4.3

③6.6

④15.7

No.

①1.7

②0.6

③1.3

④4.7

I don’t know.

①3.5

②1.7

③3.1

④7.6

No answer.

①0.9

②1.4

③0.9

④0.0

Do you think the reality of the damage caused by the atomic bombings is widely known in your country?

It is widely known.

①9.7

②5.7

③12.8

④14.0

It is known to some extent.

①46.3

②42.9

③50.7

④47.7

It is not widely known.

①33.9

②39.1

③28.2

④30.8

Few people know about it.

①7.3

②9.7

③4.8

④5.8

I don’t know.

①2.5

②2.6

③3.1

④1.7

No answer.

①0.1

②0.0

③0.4

④0.0

How can the A-bomb survivors convey their accounts to the world more widely and what should be done to promote the abolition of nuclear weapons? (Circle up to three answers.)

Focus on the inhumanity of nuclear weapons and make efforts to convey this to the international community.

①62.3

②61.4

③60.4

④66.9

Press the Japanese government to play a leadership role at the United Nations and at international conferences.

①25.4

②27.7

③22.9

④23.8

Appeal to the U.S. government and the American public to motivate the United States to take stronger action.

①21.9

②20.6

③19.8

④27.3

The Japanese people should face up to the wartime atrocities they perpetrated in Asia and reconsider the nation’s current actions.

①17.6

②20.6

③16.3

④13.4

Turn our attention to the damage caused by war in other parts of the world and promote nuclear abolition by working with war victims.

①40.3

②41.7

③36.1

④43.0

Highlight the harm caused by radiation from nuclear tests and nuclear accidents, and strengthen the movement to end the use of nuclear energy.

①25.0

②14.6

③22.9

④48.8

Other.

①3.3

②2.9

③1.3

④7.0

I don’t know.

①4.8

②2.9

③7.0

④5.8

(Originally published on May 9, 2015)