Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized Students 8

Aug. 3, 2015

Girls went to work for the war effort, singing for a fighting spirit

Yoshie Ishikawa (nee Ishida), 86, a resident of Naka Ward, has photographs of mobilized students from World War II. On the back of these photos is stamped “Censored by transportation department of the army on July 17, 1944.” The photos are precious reminders of the mobilized students who went to work for an arms maker under the government’s authority during the war.

Head covered, working at a lathe

Ms. Ishikawa has five photos, including a picture of herself as a fourth-year student from the Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School. Her head covered, she faces a lathe. Another picture shows schoolmates chatting during a break. These photos were taken at Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda Motor Corporation) in Fuchu, Hiroshima Prefecture, a factory where firearms were produced. “I don’t know who took these photos or why they were taken,” she said. Then, the words still in memory, she sang a song that she used to sing with her friends at the time: “We are the young buds of cherry blossoms. We dedicate our lives to the nation’s important affairs for our honor as students. Our red blood is ablaze with zeal.”

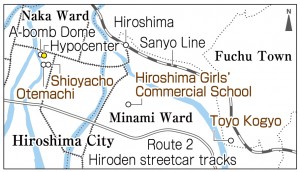

The song is entitled “Ah kurenai no chi wa moyuru” (“Our Red Blood is Ablaze with Zeal”), which the Japanese government designated as “a song for the mobilized students.” Ms. Ishikawa and her schoolmates sang it when going to work as a group after gathering at Mukainada station. Her school was located in Minamidanbara-cho (part of today’s Minami Ward) and about 100 fourth-year students were mobilized to work at Toyo Kogyo for the whole year.

From the spring of 1945, Ms. Ishikawa continued her work as a mobilized student. Because her family’s home in Shioyacho (part of today’s Naka Ward) was demolished in the effort to create fire lanes, she moved to a house in the neighboring Otemachi district with her mother and older sister. Her father, who worked at a branch of Hiroshima Chokin Bank, had been drafted into the military.

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb on August 6, Ms. Ishikawa was working as a bookkeeping clerk in the main building of the plant. Though the building was located about 5.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, the window glass was blown out by the blast. Amid the panic of these conditions, she and some schoolmates went to nearby Aosaki National School because, as mobilized students, they felt they had to help provide first aid to the wounded.

“Many of the younger students from our school also fled to this aid station. They were pleading for water, their burned skin hanging from their bodies. If I had known they were going to die, I would have given them water,” she said. First- and second-year students from the Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School suffered the atomic bombing while helping to tear down buildings to create a fire lane in the area west of the Tsurumi Bridge (part of today’s Naka Ward). As far as could be confirmed, 274 of these students were killed.

As she traced her memories of her days as a mobilized student, the words gushed forth, but became tinged with sorrow as she recalled her experience. The day after the bombing she walked through the ruins of the city, weeping and calling out for her mother, then sleeping under the sky at night.

She was unable to find her mother, Natsuyo, who was 49. But she reunited with her older sister, who experienced the bombing near the Sumiyoshi Bridge (part of today’s Naka Ward) and jumped into the Honkawa River. On August 15, when the emperor’s broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender was aired, she was in the present-day town of Kitahiroshima, her father’s hometown.

Small piece of bone found at fire cistern

“One mysterious thing happened,” Ms. Ishikawa said, her tone lifting again.

On August 6, 1946, the year after the atomic bombing, she was visiting the site in Otemachi where her old house had stood, where there were now shacks, to pray for the repose of her mother’s soul. When she peered into the fire cistern there, she found a small piece of bone. She then placed this bone fragment in the family tomb, believing she was brought to it for a reason.

“I didn’t know about that,” said Mineko Ishida, 67, a resident of Naka Ward, who had accompanied Ms. Ishikawa to the interview. Ms. Ishida is her half-sister on her father’s side and she was listening to Ms. Ishikawa’s story of the atomic bombing for the first time. Ms. Ishida frequently visits her sister, who lives alone and has become less mobile due to weakening legs. Ms. Ishida’s late mother, Setsuko, also lost her family in the atomic bombing, then married Ms. Ishikawa’s father, Kiroku. Ms. Ishida was born from their union.

Noboru Ishikawa, Ms. Ishikawa’s late husband (who died in 2012 at the age of 87), was born in Otemachi, too. After returning from military service, he found that his parents and siblings had perished. After they wed, they went on with their lives, never discussing the atomic bombing between themselves. Ms. Ishikawa continued her bookkeeping work while raising a family before she retired at the age of 70.

“We were brainwashed by the slogan ‘Fight to the death’ and we endured this situation even after the severe damaged we suffered because of the atomic bombing. But war should never be acceptable. Recently, the new security bills are making news. I don’t think we should risk experiencing those horrific times again.”

According to the Student Labor Service Order issued by the government, boys and girls were forced to serve as “volunteers” to engage in “vital work for the state.” About 7,200 mobilized students lost their lives as a result of the atomic bombing. Even those that survived had to endure tremendous hardships.

Ms. Ishikawa’s photos, which were taken in the time when mobilized students sang the “Red Blood” song to stir their spirit, happened to be put into her bag on the day of the bombing because her schoolmates had asked to see them.

(Originally published on August 3, 2015)