Hiroshima: 70 Years After the A-bombing: Mobilized Students 7

Jul. 31, 2015

Named on monument to victims of the post office, but still alive

This summer, after agreeing to an interview with the Chugoku Shimbun, Takashige Saito, 83, a resident of Kuchita-minami, Asakita Ward, visited a monument at Tamon-in Temple in the Hijiyama district in Minami Ward. Mr. Saito was accompanied by Masaharu Shiomi, 25, one of his grandchildren and a resident of Mitaki-honmachi, Nishi Ward, for the first time.

“I would have died if I had reported for work,” said Mr. Saito. Although he tried to continue sharing his memories with his grandson, his voice faltered as emotions rose. Inscribed on the Monument to the Employees of the Hiroshima Post Office are 288 names, including the name “Takashige Saito.” Back then, Mr. Saito was a second-year student in the advanced course at Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward), which corresponds to an 8th grade level.

The students in the advanced course at national schools were mobilized under the Student Labor Service Order issued by the Japanese government in 1944. Starting in April 1945, all classes were canceled, as a rule, except classes for students in the elementary course at national schools.

Mail service continues with two-wheeled cart

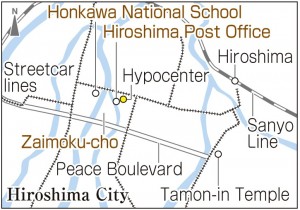

The Hiroshima Post Office was located in Saiku-machi (now Ote-machi in Naka Ward). Mr. Saito, dubbed a “communications soldier,” went to the office around 8 a.m. and began delivering mail from a big shoulder bag in the Koi district (in today’s Nishi Ward). In the afternoon, Mr. Saito and an adult worker pushed a two-wheeled cart laden with parcels while collecting and delivering mail in an area straddling the Kamiya-cho and Takanobashi districts (in today’s Naka Ward).

He lived in Zaimoku-cho, an area that has become part of today’s Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Because his parents had died earlier--his mother in childbirth and his father from illness--he was living at the home of his uncle, who ran a cotton mill, with his grandmother, his older sister, and his older brother.

On August 6, Mr. Saito was in the city of Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture, accompanying his uncle on a visit to an acquaintance. He returned to Hiroshima the following day, entering the hypocenter area in the afternoon. By checking sites where his relatives had evacuated and aid stations for the wounded, he managed to find his brother one week after the bombing.

But he was unable to locate his grandmother, Ichi Kimura, 65; his aunt, Kimi Kimura, 46; his sister, Kikue Saito, 17; and Fumio Kimura, 24, another uncle who happened to be staying with the family that day. Mr. Saito said, “I gathered up bones at the burnt site of the house. But there were frequent visitors to the house, too, so I have no idea whether or not the remains were family members.”

The three-story Hiroshima Post Office, built of brick and roof tiles, was located across from the Shima Hospital, known as the bomb’s hypocenter. A grave post for the dead was erected at the former site of the post office building, but reconstruction in the city forced this marker to be relocated. In 1953, the monument engraved with the names of post office employees who died on duty was rasied at Tamon-in Temple.

The memorial book Ishibumi (Monument), published in 1977, indicates that Mr. Saito “died at the Hiroshima Post Office on August 6.” His name was among 222 staff members of the post office, 48 mobilized students from Gion Girls’ High School (including a teacher), and 16 mobilized students from the advanced course at Honkawa National School (including a teacher).

Mr. Saito learned about this in 2000. He was interviewed by the Chugoku Shimbun for the feature article “Photographs of the Dead Speak,” which traced those who died in the vicinity of the hypocenter. He reunited with one classmate (who passed away in 2003), whose name was also erroneously inscribed on the monument.

Before the monument, which still carries his name as a victim of the A-bomb attack, he talked about his life after the bombing.

“I devoted my energy to just getting on with my life,” Mr. Saito said. He did not return to school or to the post office. He had no choice but to keep working, first at the Hiroshima Railway Bureau (now JR West), then at a manufacturer in Nishi Ward. He got married in 1961 and had two daughters. For over 30 years, until the mandatory retirement age, he continued working for the same company. He now has five grandchildren, too.

Handing down his grandfather’s message

“I don’t want to have my name removed from the monument. To me, it’s proof that I survived,” Mr. Saito said. Listening attentively to these honest feelings was his grandson, Masaharu, who lived with Mr. Saito until he became a company worker.

Masaharu said that, even with family members, his grandfather is reticent and has spoken little about his A-bomb experience. After learning two years ago that his grandfather planned to share his account at a gathering called the Hiroshima Fieldwork, where the participants visit the hypocenter area of the atomic bombing, Masaharu took part. His interest in his grandfather’s experience grew after the Great East Japan Earthquake and accident at the Fukushima Daiichi (No. 1) nuclear power plant in March 2011.

In a halting voice, Mr. Saito explained why he now spoke more openly about his experience, saying, “People who experienced this have to share their experiences.” Added Masaharu, “The family understands what’s in his mind. And I think this is a message we can continue to hand down for him.”

(Originally published on July 20, 2015)