Hiroshima Asks: Toward the 70th Anniversary of the Atomic Bombing: Report on survey of A-bomb survivors living abroad

May 18, 2015

by Masakazu Domen, Yumi Kanazaki, Yota Baba, and Keiichiro Yamamoto, Staff Writers

A survey of A-bomb survivors living in South Korea, North America, and South America has been carried out, timed for the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings. The results show how survivors overseas have been making efforts to convey their experiences and how they have suffered distress in the midst of social environments that are different from conditions in Japan. In addition to conducting the survey, the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed eight Hiroshima A-bomb survivors, mainly the leaders of survivors’ movements in different countries. This article explores what survivors living overseas think of their experiences, how they hope their memories will be handed down, and what requests they have regarding support for survivors.

Today, there are still a large number of nuclear weapons in the world. To prevent another tragedy like Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is vital that the A-bomb accounts of the survivors’ experiences be shared throughout the world and handed down to the next generation.

But the survey results show that survivors living overseas lack opportunities to share their experiences in public settings. Unlike survivors in Japan, in many cases their experiences are shared only between them and their children or grandchildren, and are not often conveyed to a larger groups of people. To the question “Do you think that people in your country are aware of the damage caused by the atomic bombings and the actual conditions of the survivors?”, 53.3 percent of the respondents answered either “Not very much” or “Hardly at all.”

The reasons vary by region. In North America (the United States and Canada), more than 70 percent of the respondents chose “Because people aren’t willing to face the horrors of the atomic bombings.” (Multiple answers were allowed.) This contrasts sharply with 16.0 percent in South America and 23.5 percent in South Korea. To view the atomic bombings in a positive light, the American public tends to neglect inconvenient facts. This suggests the conflicted feelings held by survivors living in the United States. In South Korea, “Because survivors haven’t talked about their experiences due to fears of discrimination” was chosen by 30.6 percent of the respondents, which is more than double the percentages in North and South America.

Still, many survivors believe that the appeals from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have a universal significance. Asked whether the experiences of the atomic bombings have had an impact on peace in the world or the prevention of nuclear warfare, a total of 70.9 percent of the respondents chose either “Yes” or “To some degree.” This can be interpreted as a sign that they are all the more aware of the importance of their experiences amid conditions different from those in Japan.

Survivors were also asked to freely describe their hopes for young people. “I hope to see Korean youth leading efforts to prevent nuclear war by working together with young people around the world.” (Man in his 70s, South Korea) “There are many young people who are against nuclear weapons, though they don’t have detailed knowledge about the actual state of the survivors. I hope that they, as the world’s conscience, will continue to raise their voices against nuclear weapons.” (Man in his 70s, Canada) Their comments reveal the survivors’ earnest desire that the younger generation will advance closer to a world without nuclear weapons than their generation could.

Majority absolutely reject nuclear weapons

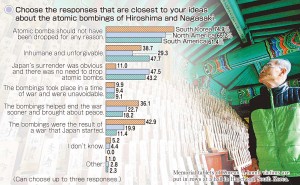

Responses to a question concerning the rights and wrongs of the atomic bombings show that the majority of the survivors absolutely reject nuclear weapons.

“Atomic bombs should not have been dropped for any reason,” which expresses the strongest rejection, was chosen by 69.2 percent of all respondents. (Multiple choices were allowed.) By region, 74.9 percent in South Korea, 65.2 percent in North America, and 61.4 in South America selected this response, close to the figure of 73.7 percent in Japan. These results convey the true feelings of survivors who directly experienced the event. Percentages of those who chose “The bombings took place in a time of war and were unavoidable” held at the nine percent level in all three regions.

On the other hand, the percentages of people who chose “The bombings were the result of a war that Japan started” varied greatly by region. In South Korea, 42.9 percent chose this response, while the figures were 19.9 percent in North America and 11.4 percent in South America.

The high percentage recorded in South Korea can be attributed to resentment felt against Japan’s long colonial rule before the atomic bombings. In North America, there was a much lower figure of 18.2 percent among U.S. respondents. Public opinion in the United States may be similar to this choice because of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. But the low percentage could reflect the A-bomb survivors’ unexpressed discontent with such public opinion.

Another choice that revealed large regional differences was “Japan’s surrender was obvious and there was no need to drop the atomic bombs.” In North and South America, almost 50 percent of the respondents chose this response, like in Japan. But only 10 percent of South Korean survivors chose this response. Though all the respondents equally reject the atrocity of the nuclear attacks, this difference highlights the gap in perceptions of history leading up to the atomic bombings.

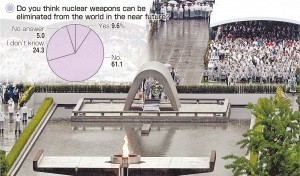

The United States is a nuclear superpower. South Korea is in the midst of a prolonged truce with nuclear-armed North Korea. Living in conditions that are different than those in Japan, survivors overseas have come to recognize the great difficulty of abolishing nuclear arms.

Asked whether they think nuclear weapons can be eliminated from the world in the near future, 61.1 percent of the respondents answered “No,” which is slightly higher than the figure of 58.2 percent in Japan. By region, the figures are 66.0 percent in South Korea, 56.4 in North America, and 59.1 in South America. The percentage was notably high in South Korea, which neighbors North Korea, and beyond North Korea are China and Russia, both nuclear powers. At the same time, 9.6 percent of all respondents answered “Yes,” which is lower than Japan’s percentage of 13.0.

Nevertheless, people expressed strong hopes for nuclear abolition in a section where they could freely write comments. “Nuclear weapons, which are capable of wiping out mankind, must be eliminated from the earth. This is not a problem for the next generation. The political leaders of the world must solve this problem now through international cooperation.” (Man in his 70s, South Korea) Many called upon Japan to act as the nation which experienced the atomic bombings. “Japan should be more aware of and emphasize its responsibility as the nation that experienced the atomic bombings, more actively involved in conveying the horrors of nuclear warfare and appealing for world peace.” (Woman in her 70s, the United States)

The survey results show that 70 percent of survivors living outside Japan believe that the A-bomb experiences have contributed to preserving peace in the world and preventing nuclear war from breaking out. How can these experiences make even greater contributions across national borders and how can they be passed down to the next generation? The cooperation of survivors and citizens in Japan with the people of other nations will be put to the test.

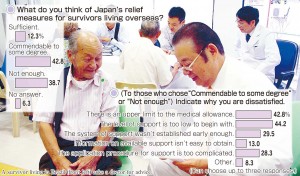

Discontent remains regarding ceiling on relief benefits

In their comments, many expressed anxiety about their health and discontent with relief measures, which lag far behind those provided in Japan.

In particular, close to 80 percent of South Korean survivors describe themselves as “prone to illness” or “bedridden,” much higher than in North and South America or in Japan, where the percentage was 26.7. South Korea’s high percentage may have resulted from the large proportion of people who were directly exposed to the radiation of the atomic bomb close to the hypocenter and also from the fact that Korean survivors had only limited opportunities to receive medical treatment when they were younger.

Asked whether the atomic bombing has something to do with the diseases the survivors have developed, more than 50 percent responded “Yes” in North and South America and Japan, but the figure was 74.4 percent in South Korea. A similar pattern is seen in the responses to “Do you still think back to the atomic bombing and struggle with a strong sense of anxiety?”

Previously, the Japanese government provided support only to survivors living in Japan. Though the gap in relief between those living in Japan and abroad has slowly narrowed, people remain dissatisfied and are particularly concerned about subsidies for medical expenses.

In Japan, survivors are entitled to free medical treatment, but there has been a ceiling for subsidies given to A-bomb survivors living outside of Japan. Among those who said that they were dissatisfied, the percentages were 36.6 percent in South Korea, 48.1 in North America, and 58.6 in South America. (Multiple answers were allowed.)

The comments written by Korean survivors show that they consider this to be part of the compensation for damages caused during the war. Japan’s Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry raised the ceiling significantly last fiscal year.

--------------------

Lee Ilsu, 85, resident of Busan, South Korea

I can’t believe 70 years have already passed since the atomic bombing. The lives of our generation have been filled with war, World War II and then the Korean War. We didn’t receive enough education and were forced to work at factories or outdoors, and we lost people close to us…

The people who experienced the horrors of the atomic bombing understand this misery. I was in the Ozu area (in Minami Ward, Hiroshima) when the atomic bomb was dropped, but I survived. I saw many victims, their bodies covered with maggots. I hate atomic bombing. We must get rid of nuclear weapons.

I came back to Hapcheon, South Korea with my family in November 1945. It became the site of a hard-fought battle in the Korean War, which began in 1950. My mother lamented that it was even scarier than the atomic bombing, but she died soon after that. She had already been suffering from the aftereffects of the bombing in Hiroshima.

After returning to my country, I had a hard time for a little while because I couldn’t read Korean. I moved to Busan with my husband, and a branch office of the Korean Atomic Bomb Victim Association opened there. I helped with applications for benefits as I could understand Japanese.

Survivors residing outside of Japan lived without any support for a long time. Japanese citizens’ groups helped us file lawsuits, and finally we’re able to receive support. We’re not demanding any more support than the Japanese survivors receive. We just hope that the gap can be reduced between us and the Japanese survivors.

Sim Jintae, 72, resident of Hapcheon County, South Gyeongsang Province, South Korea

Support for survivors living overseas has lagged far behind the support for Japanese survivors. It was only in 2003 that the directive by the former Health and Welfare Ministry was repealed. The directive prevented survivors living outside Japan from receiving the benefits of medical treatment overseas. Survivors are survivors no matter where they live. All the survivors must be treated the same.

It is also a matter of post-war reparations. The Japanese government’s stance is that postwar compensation has been resolved with the Korea-Japan Claims Settlement Agreement, which was adopted 50 years ago. But as one of the Korean survivors who has been kept out of the loop, I don’t think the problem has been settled. In 2011, the Constitutional Court of Korea ruled that neglecting the issue of the right to seek damages is unconstitutional and demanded that the South Korean government address this problem. The governments of both countries must take responsibility for resolving this issue.

At the time of the atomic bombing, I was two years old and I was in Eba (in Naka Ward, Hiroshima). My family returned to Korea the following month, but my father was drawn into the Korean War and was killed in 1950.

It has become extremely hard for survivors living in Korea to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. People who were very young at the time and don’t have memories of the atomic bombing must rely on their parents’ testimonies. But if they missed the chance to ask their parents about what happened, it’s very hard to gather enough evidence, as required. At the Hapcheon branch of the Korea Atomic Bomb Victim Association, survey sheets from about 6,000 survivors are kept for safekeeping. These documents should be fully utilized in supporting the survivors.

Won Jungboo, 74, resident of Seoul, South Korea

I wish I had known about the terrible effects of radiation from the atomic bomb earlier. Survivors who returned to South Korea couldn’t get enough information and were unable to receive adequate medical treatment. I think this situation hastened the deaths of many people.

I was at my house in Kamitenma-cho (in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima) with my mother, grandmother, and three brothers when the bomb exploded. We spent one week in our half-destroyed house. Because we heard that strange diseases were spreading, we moved to a mountainous area and returned to our country at the end of 1945. My mother and youngest brother were in our garden at the time of the bombing and were apparently exposed to a large amount of radiation. They died within a year or two. I’m doing well now but worry about my health.

Survivors living in South Korea are facing the problems of restoring our human rights and honor, which had been denied. We spent a long time without knowledge of the horrible effects of radiation from the atomic bomb. After the normalization of ties between South Korea and Japan in 1965, it became easier to gain information, but then we had to suffer from discrimination. This is a domestic problem in South Korea, but the prejudice is deeply rooted.

It’s unacceptable that there is a gap in relief measures between those living in Japan and those living abroad. The United States is responsible for the bombings, but Japan created the cause for Koreans to become A-bomb survivors, as many people were forced to work in Hiroshima or Nagasaki because of Japan’s colonial rule. As this year marks the 50th anniversary of the normalization of ties between the two countries, these past problems should be properly settled.

Mariko Lindsey, 69, resident of Hercules, California, the United States

I was born in April 1946 and was still in my mother’s womb at the time of the atomic bombing. My mother was pregnant and encountered the explosion about 1.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. She was on her way from Otake to her assigned work, helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane. When she came to, she realized that her clothes had been blown off her body and the lunch box she was carrying had also been blown away, leaving only the handle.

After finishing high school in Hiroshima, I went by myself to the United States to study social welfare. I helped the Committee of A-bomb Survivors in the U.S.A., and my friends and I collected accounts of A-bomb survivors living in the United States. I started to think about my mother’s experience of the bombing. I was about 40 then.

My mother didn’t bring up the subject herself, and I know very little about her experience. I’m keenly aware that this is something I should have learned and conveyed to others.

The biggest problem survivors living in the United States face is the medical costs, which are often quite high. Medicare, which is a public health insurance program for the elderly, doesn’t cover these costs, so many survivors buy private health plans on their own. Now there’s a system to cover a portion of the medical costs, but you have to go through a cumbersome procedure. Many people hope their insurance premiums will be subsidized. It would be nice if we could choose from different options. The relief system should be made flexible to meet the needs of conditions in each country.

Junji Sarashina, 86, resident of Buena Park, California, the United States

It’s hard to hand down our experiences of the atomic bombing in the United States. There are many things that trouble us. Many of the survivors haven’t mentioned their experience out of fears like “My insurance policy might be canceled” or “There may be discrimination when it comes to the marriage prospects of family members.” I’m not sure whether my grandchildren’s generation understand the word “hibakusha.”

I belong to the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors (ASA). The ASA is facing financial difficulty, and the annual fees paid by members cover only postage. Our members are old, and the group’s survival will depend on the second generation.

I was born in Hawaii and moved to Hiroshima, where my parents were from, before the Pacific War broke out. When I was a third-year student at the former Hiroshima First Middle School, I experienced the atomic bombing at a factory in Kanon (in Nishi Ward). I helped cremate the bodies of many of my classmates.

After I went back to Hawaii, I was drafted to serve in the Korean War. Later I moved to California. Working for a Buddhist organization has given me emotional support. I appreciate the medical checkups and consultations provided by the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association. I’m filled with a special feeling of ease when I can talk with doctors using the Hiroshima dialect.

The path toward the elimination of nuclear weapons is a long uphill road. If the president of the United States were to declare that the whole nuclear arsenal would be dismantled, he or she would be immediately driven from office. However, despite all this, I believe politicians have the responsibility to move things forward.

Setsuko Thurlow, 83, resident of Toronto, Canada

I was 13 and working as a mobilized student at the Imperial Japanese Army’s Second General Headquarters in Futaba no Sato (in Higashi Ward, Hiroshima) when the A-bomb was dropped. I still remember the event clearly. Instead of telling only how horrible the bombing was, I hope to convey how the survivors rose from the ashes and how they have searched for meaning in their lives.

I moved to Canada in 1955 and have been sharing my A-bomb experience with others. While I was studying in the United States, a newspaper reporter asked me to comment on a U.S. hydrogen bomb test conducted at the Bikini Atoll. I made a critical remark, and I received anonymous letters that were threatening. I was scared, but this experience made me determined to make it my mission to tell the story of Hiroshima for the survival of the human race.

Handing down the A-bomb accounts is a difficult challenge. No one can really tell my experience for me, but people can convey our thoughts and vision based on their understanding of our experiences. I asked my son to give a speech at the “Hiroshima Day” peace gathering held in Toronto two years ago. I felt happy when he accepted the invitation, saying he felt honored. Maybe he’s aware of his identity as a second-generation hibakusha.

Even if you aren’t a hibakusha, your voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have power. To realize a world without nuclear weapons, each and every one of you should take your responsibility to heart and make efforts, especially, to move the Japanese government.

Mitsuo Tomozawa, 85, resident of Whittier, California, the United States

I experienced the atomic bombing in the Kasumi-cho area (in Minami Ward, Hiroshima) and was conscripted to serve in the Korean War, but I survived. When I learned that there are other A-bomb survivors in the United States, I thought God made me live to work for them and I’ve been involved in the survivors’ movement ever since. Now I’m active as a member of the North America A-Bomb Survivors Association.

There were different opinions among members, but I believe the discriminatory treatment toward survivors living outside Japan has been reduced through legal battles. We worked together with survivors in Brazil and South Korea, and with the help from lawyers in Hiroshima and others, we won these cases.

I’m a second-generation Japanese American and I was born in Hawaii. My parents wanted me to be educated in Japan, and sent me to Hiroshima when I was 10. Three years after the atomic bombing, I went back to Hawaii. I had lost most of my English and then I got drafted, so it took time to enter a higher-level school. I studied under adversity.

When I gave my account here, I always received telephone calls or letters the following day. The anonymous messages said, “Go back to Japan.” I’ve tried to convey my thoughts as a pacifist, but after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States, I sometimes feel that I’m just wasting my breath. But I still remember what happened when the bomb was dropped, as if it happened yesterday. I hope to help build a peaceful world for my children and grandchildren.

Junko Nakauchi, 70, resident of Sao Jose dos Campos, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Suffering from diabetes, kidney disease, and anemia at the same time, I spent two weeks in a hospital in Brazil last July. It cost 1.7 million yen. Unlike in Japan, we don’t have a good public health insurance system in Brazil. I found out that treatment undertaken right after taking out a private insurance policy isn’t covered by insurance. So I had to take out an eight-year loan at the bank to pay the medical bills.

I know that survivors can receive treatment without bearing the expense themselves if we travel to Japan. But I’ve been receiving dialysis treatment and can’t possibly go to Japan. There’s a subsidy program, but I’d like a system which covers medical costs, like in Japan. But if it takes time to implement such a system, it would be pointless.

I was only a year old and at my house in Senda-machi (in Naka Ward, Hiroshima) when the bomb was dropped. We were not well off, partly because my father was exposed to radiation from the bomb. About 10 years after the end of the war, he had health problems and was hospitalized. He used to run a taxi company, but he had to close his business. Several years after our family moved to Brazil, he became bedridden.

I was 15 when I came to Brazil. I did nothing but work on farms from morning to night to help provide for the family. As I couldn’t go to high school, I couldn’t get a better-paying job. The atomic bombing impacted not only the victims’ lives but also the lives of their children and grandchildren. I want people to know this.

--------------------

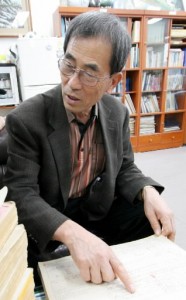

Interview with Noriyuki Kawano, professor at the Institute for Peace Science at Hiroshima University

What can we learn from the results of the survey?

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Noriyuki Kawano, professor at the Institute for Peace Science at Hiroshima University, who has interviewed many A-bomb survivors living overseas and victims of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident in the former Soviet Union.

The perceptions of Korean survivors differ from survivors living in North America and South America. For survivors living in North and South America, the suffering started at the moment of the atomic bombing and has continued for the past 70 years. But Korean survivors have a longer history of suffering. They were under Japan’s colonial rule before the atomic bombings. Their suffering didn’t begin on August 6 or 9, 1945.

They ask themselves why they had to be in Japan at that time and face the atomic bombings. They have a history of suffering without proper support, caught between the irresponsibility of Tokyo and the indifference of Seoul. We should interpret the results of the survey based on these points.

What about the survey draws your attention?

Compared to survivors in North and South America, many of the Korean respondents were very young at the time of the bombing. But a large number of people answered that they believe their diseases can be traced to the bombing or that they still struggle with a strong sense of anxiety. Even if they don’t have clear memories of that horrible day, it’s possible that they perceive the atomic bombing as part of a series of experiences, which include the chaotic times and financial hardships they endured after returning to their country.

Asked why they haven’t talked about their A-bomb experience, many Korean survivors said they were fearful of discrimination. What are your thoughts? They may have thought they would be discriminated against not only because they were A-bomb survivors but also because of the very fact that they lived in Japan. Some Koreans were accused by their countrymen of being pro-Japan. This might have contributed to Korean survivors having had limited occasions to share their A-bomb experience.

Do you see regional differences in terms of how the survivors interpret the pros and cons of the atomic bombings?

In North and South America, many people answered that the bombings were unnecessary. I think this comes from their self-awareness that they are originally Japanese. While many Korean survivors chose the answer “Atomic bombs should not have been dropped for any reason,” many also chose “The bombings helped end the war sooner and brought about peace” or “The bombings were the result of a war that Japan started.” They feel that the bombings were “unforgivable” not by reason but by feeling, yet at the same time they think the bombings liberated them from Japan’s colonial rule. This might seem paradoxical, but these conflicting feelings coexist in their minds.

In their comments, they expressed their belief that nuclear weapons must never be used.

It is a common desire that a world without nuclear weapons should be realized and that Japan should continue on the path of being a peaceful nation. They also demand that the same support that the Japanese survivors receive be given to them.

It is estimated that tens of thousands of people from overseas were in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped. But we don’t really give consideration to those people when we think about the atomic bombing. We should be more aware of the fact that those who suffer aren’t only in Japan but in other countries as well.

Profile

Noriyuki Kawano

Born in Kagoshima Prefecture in 1966. Earned a Ph.D. from Hiroshima University’s Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. Served in various posts including assistant professor at the university’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, and associate professor at the Institute for Peace Science at Hiroshima University. Assumed his present post in 2013. Specializes in the study of the atomic bombings, exposure to radiation, and peace studies.

--------------------

Survivors’ comments

Fighting against illness in senior years

After my children grew up, my life became easier. But that was for a very short period of time. As I get older, my life has been filled with struggles with illness. I want the Japanese government to apply the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law to all the survivors living abroad. (Man in his 70s)

Feeling frustrated with life filled with suffering

I was haunted by nightmares of the atomic bombing and had to be treated by a psychiatrist. I often collapsed and my children were worried. The atomic bombing affected my marriage, and my entire life has been filled with suffering. I feel such frustration. (Woman in her 70s)

Education of A-bomb damage is essential

It seems many young South Koreans are indifferent to North Korea’s nuclear issues. The government must give sufficient information and continuous education so that people will renew their awareness of the damage caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (Man in his 80s)

Share A-bomb experiences with young people all over the world

The day I experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima is the day my father and brother died. I still cry when I remember that day. I hope that the young people of the world will work to build nations that won’t have nuclear weapons or wars. Let’s share our A-bomb experiences with more and more young people around the world. (Man in his 80s)

Japan should lead nuclear abolition movement

Japan caused Korean people to be exposed to the atomic bombings. It was also the first nation to suffer nuclear attacks. It must lead the movement in mobilizing international opinion for world peace and the abolition of nuclear weapons. Otherwise, the international community will not respect Japan. (Man in his 70s)

Survivors living in South Korea should receive compensation

I stress that Japan will be respected by the entire world and wash itself of past sins if the Japanese government immediately compensates A-bomb survivors in South Korea. (Man in his 70s)

Same support must be given in Japan and abroad

I believe South Korean survivors should be entitled to the same medical support as given in Japan. I hope Japanese people will help realize this. (Man in his 70s)

Korean government should recognize survivors’ service

The South Korean government should enforce a special law to recognize the service of A-bomb survivors living in the country. The Japanese government should also acknowledge and apologize for the nation’s past mistakes. (Man in his 70s)

North America

Heart bleeds when remember people begging for water

As a survivor, I strongly hope that such a terrible thing never happens again. My heart still bleeds for people whose entire bodies were badly burned, leaning against a wall and begging for water with trembling hands. (Woman in her 80s)

Nuclear umbrella disappointing

It’s disappointing that Japan, protected under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, can’t make a strong appeal for nuclear disarmament to the U.S. Other nuclear powers are against nuclear arms reduction. I am pessimistic, afraid that nothing will change until another catastrophe occurs. (Man in his 80s)

“Pearl Harbor” common response

When the atomic bombings are raised, Americans always respond by pointing to “the attack on Pearl Harbor.” I want to say to the young generation that Japan must never be the one to start a war and should strive to keep the peace. (Woman in her 80s)

Justification of atomic bombings unforgivable

The United States has justified the atomic bombings and not provided reparations to victims. This is unforgivable. (Woman in her 70s)

Denied private insurance

I was denied private insurance because I’m an A-bomb survivor, so I had to bear all my medical costs until I could access public insurance at the age of 65. I often had to return to Japan and ask family members to help me with my medical expenses. (Woman in her 80s)

U.S. government must implement relief measures

Not only the Japanese government but also the U.S. government should implement relief measures. If the U.S. hadn’t dropped the bomb, I wouldn’t have to be suffering from illnesses of unknown causes. (Woman in her 80s)

Application procedures too complicated

Application procedures for subsidies for medical expenses are too complicated. To an elderly person living alone, it seems like an unreasonable demand. (Man in his 70s)

Satisfied with amount of medical expense subsidy

I am grateful that survivors, including those who moved to other countries, are now granted financial support for their medical expenses. I haven’t had any major illnesses. I’m satisfied with the amount of the allowance. (Woman younger than 70)

Survivors are survivors no matter where they live

Survivors living outside Japan have been treated unfairly with the upper limit to the medical expense subsidies they can receive. I filed a lawsuit and have written to the Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry from time to time, but have not received any reply. We are hibakushas no matter where we live. (Woman in her 80s)

Japan should stick to pacifist Constitution

Japan should stick to its pacifist Constitution. The root of conflicts in this modern world is the growing disparity between the rich and the poor. With this in mind, Japan should face the situation and strive to reduce this disparity. (Man in his 90s)

South America

Don’t forget survivors living overseas

Take seriously the fact that many Japanese nationals are suffering as A-bomb survivors. Don’t forget that there are Japanese nationals who have moved to a different country but continue to take pride in their love for Japan. (Woman in her 70s)

Don’t make war

People’s egos and war will not lead to world peace. Don’t make war. This is what I want to tell young people around the world. (Woman in her 90s)

Worried about the ceiling in subsidy

As I grow older, my medical expenses have gotten heavier. The upper limit of the amount of subsidy is a source of terrible anxiety. I can’t understand why there should be a difference between those living inside and outside Japan when it comes to relief measures. Does it mean that the Japanese government doesn’t consider Japanese nationals living abroad as Japanese? (Woman in her 70s)

Living in a foreign country, high barriers

There are many difficulties in living in a foreign country. When we can’t give detailed explanations about our conditions because of the language barrier, we can’t receive adequate medical treatment. When I went to Japan, I demanded that I receive a nursing aid allowance but was denied, because it applies only to those living in Japan. I was very disappointed. (Woman in her 70s)

--------------------

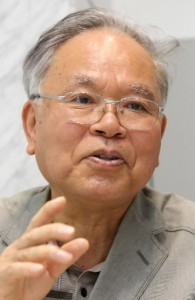

Excerpt of interview with Kazuyuki Tamura, professor emeritus of Hiroshima University

Japan first enacted the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law, which involved medical care for survivors, and the A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law, which dictated the payment of benefits. The government’s stance was that survivors living outside Japan weren’t covered by these laws. This stance didn’t change when the two laws were integrated into the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law in 1994.

But for the past 10 years, the gap has been gradually narrowed. Directive No. 402, issued by the former Health and Welfare Ministry, stipulated that if a recipient leaves Japan, he or she will no longer be eligible for a health management allowance and other benefits. That directive was repealed in 2003. Now survivors living overseas can apply for the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate, other benefits, and the A-bomb disease certification without coming to Japan. This has been realized through lawsuits filed and won by survivors living abroad, which forced the Japanese government to reform the system.

The last big barrier to overcome involves the medical allowance. The Japanese government has taken the stance that the A-bomb Survivors Relief Law doesn’t apply to survivors living overseas. The government has allocated its budgets to a separate program and put a ceiling on the amount of subsidy. Survivors have filed lawsuits in different parts of the country for the full payment of their medical expenses. The Hiroshima district court will hand down a ruling on June 17.

Last fiscal year, the ceiling was raised from 180,000 to 300,000 yen a year. If their medical expenses exceed the ceiling, they can apply for reimbursement to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. But we can’t say that the problem has been solved. Can elderly survivors fill out the extremely complicated application form? Even if they can, how many of them will be able to pass the screening process? And what will happen to the money they pay out of their own pockets? We have to keep a watchful eye on these developments.

Health insurance systems vary from country to country. It’s true that this is not an easy problem to solve. South Korea’s health insurance system is similar to Japan’s universal health insurance, but the coverage is limited. The United States has Medicare for elderly people, but this system isn’t sufficient and people have to buy private insurance policies on their own. They are burdened by the costs of medication and other expenses. People in Brazil have no choice but to buy private insurance and pay the annual premiums of tens of thousands yen in advance.

But these differences in the health care systems can’t justify the gap in support for survivors living inside and outside Japan. Elderly survivors don’t have much time left. They must be given support immediately.

◇

Major incidents related to A-bomb survivors residing overseas

August 1945:

Atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. According to the 1979 estimates by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the numbers of Korean survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings are 25,000 to 28,000 and 11,500 to 12,000, respectively.

April 1957:

The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is enforced.

July 1967:

The Association for the Relief of Korean Atomic Bomb Victims (now the Korea Atomic Bomb Victim Association) is founded.

September 1968:

The A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law is enforced.

December 1970:

Son Jin Doo is arrested for making an illegal entry into Japan. “I was exposed to the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and I wanted to receive medical treatment,” he explains.

October 1971:

The Committee of A-bomb Survivors in the U.S.A is established.

March 1972:

Son Jin Doo’s application for the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate is rejected. A lawsuit is filed against the City of Fukuoka.

March 1973:

Dr. Torataro Kawamura invites survivors living in South Korea for treatment at his own expense.

July 1974:

The Health and Welfare Ministry issues Directive No. 402, which stipulates that A-bomb survivors will lose their entitlements to receive public assistance benefits when they leave Japan. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government exercises its discretion and issues the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate to Shin Yong-su during his hospitalization in a Tokyo hospital.

March 1977:

First group of medical doctors is sent to the United States by the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association and other organizations.

March 1978:

Son Jin Doo wins his lawsuit at the Supreme Court.

November 1980:

Survivors living in South Korea are provided medical treatment in Japan in an experimental program run by the governments of Japan and Korea.

July 1984:

The Association of A-bomb Survivors in Brazil (the present-day Peace Association of Brazilian A-bomb Survivors) is founded.

October 1985:

Dispatched by the Hiroshima prefectural government and other organizations, doctors visit cities in South America for the first time to provide health checkups to A-bomb survivors.

July 1989:

Lee Sil Gun, chair of the Council of Atom-bombed Koreans in Hiroshima, visits North Korea and confirms the presence of A-bomb survivors in North Korea.

May 1990:

At a Japan-South Korea summit meeting, the Japanese government announces that Japan will donate 4 billion yen as financial assistance for Korean A-bomb survivors.

December 1994:

The Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law comes into force. The law contains no mention of national compensation or relief measures for A-bomb survivors living overseas.

October 1998:

Kwak Kwi Hoon, a South Korean survivor, sues the Osaka prefectural government and the Japanese government demanding a health management allowance be paid.

July 2002:

The Health Ministry implements the “Assistance Program for A-bomb Survivors Overseas” for survivors who visit Japan.

December 2002:

Kwak Kwi Hoon wins his lawsuit. The national government scraps Directive No. 402 in March 2003 and begins sending health management allowances overseas.

November 2004:

The City of Hiroshima decides to cover a portion of the medical expenses for survivors living overseas. Later, the national government takes over this task.

November 2005:

Applications for allowances begin to be accepted from outside Japan.

November 2007:

The Supreme Court rules that Directive No. 402 is unlawful and orders the national government to pay 1.2 million yen in compensation per former South Korean conscripted laborer.

December 2008:

The revised Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law takes effect, making it possible for survivors living overseas to apply for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in the country in which they live.

March 2009:

A settlement is reached in a case in which seven survivors living in South Korea demanded compensation for emotional distress as they were judged ineligible to receive relief. The Japanese government decides to pay 1.1 million yen per plaintiff.

April 2010:

It becomes possible for survivors living overseas to apply for A-bomb disease certification in the country in which they live. Applications for the Medical Checkup Certificate, for those who were caught in the “black rain,” can also be made overseas.

June 2011:

Three South Koreans, survivors and a family member of a victim, file a lawsuit, claiming it is unfair that they cannot receive full medical benefits.

November 2011:

A group of atomic bomb survivors is formed in Taipei, Taiwan.

March 2012:

Thirteen survivors living in the U.S. file a lawsuit over medical benefits.

April 2014:

The national government raises the ceiling for medical subsidies to A-bomb survivors living outside Japan from about 180,000 to 300,000 yen a year.

◇

How A-bomb survivors moved from Japan

Most of the South Korean survivors are people who came to Japan under the period of Japanese colonial rule or their children born in Japan. They moved back to South Korea after the war. Some survivors returned to North Korea through a repatriation project. Doctors dispatched by the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association visited North Korea to provide medical checkups, but the country has no diplomatic relations with Japan, and survivors are not covered by the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.

Most of the survivors living in the United States are second-generation Japanese Americans who were in Hiroshima to receive education in Japan at the time of the bombing or those who moved to the U.S. for work or marriage after the war. Most of the survivors living in South America moved there after the war through a national immigration policy. Most are still Japanese nationals.

Questions and answers (Numbers indicate percentages. Numbers were rounded off from the second decimal place, and don’t always add up to 100. The total exceeds 100 in questions to which multiple answers were allowed.)

Q= Question

Number of respondents:

A. Total (416)

B. South Korea (191)

C. North America (181)

D. South America (44)

Q. Age

Under 70:

A. 4.3

B. 4.2

C. 3.9

D. 6.8

70s:

A. 52.9

B. 67.0

C. 38.1

D. 52.3

80s:

A. 39.2

B. 27.2

C. 53.6

D. 31.8

90s:

A. 3.1

B. 1.6

C. 3.3

D. 9.1

No answer:

A. 0.5

B. 0.0

C. 1.1

D. 0.0

Q. Sex

Male:

A. 44.7

B. 60.7

C. 24.9

D. 56.8

Female:

A. 52.4

B. 37.2

C. 71.8

D. 38.6

No answer:

A. 2.9

B. 2.1

C. 3.3

D. 4.5

Q. A-bomb location

Hiroshima:

A. 85.8

B. 86.9

C. 90.1

D. 63.6

Nagasaki:

A. 9.6

B. 5.8

C. 7.7

D. 34.1

Both:

A. 0.2

B. 0.5

C. 0.0

D. 0.0

No answer:

A. 4.3

B. 6.8

C. 2.2

D. 2.3

Q. How were you exposed to the atomic bomb and its radiation?

Direct exposure within two kilometers from the hypocenter:

A. 42.5

B. 56.5

C. 31.5

D. 27.3

Direct exposure outside a two-kilometer radius from the hypocenter:

A. 34.9

B. 30.4

C. 36.5

D. 47.7

Entered within a two-kilometer radius from the hypocenter within two weeks after the atomic bombing:

A. 9.9

B. 0.5

C. 18.2

D. 15.9

Indirect exposure through rescue operations for victims without entering the hypocenter area after the bombing:

A. 2.6

B. 0.0

C. 6.1

D. 0.0

Prenatal exposure to radiation:

A. 3.4

B. 4.7

C. 2.2

D. 2.3

Was in the “First Class Health Examination Special Designated Area” (the area of heavy black rainfall) and later obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate:

A. 2.4

B. 2.1

C. 2.2

D. 4.5

No answer:

A. 4.3

B. 5.8

C. 3.3

D. 2.3

Q. Have you told about your experience of the atomic bombing to others in one way or another?

Yes:

A. 63.7

B. 52.4

C. 75.1

D. 65.9

No:

A. 34.4

B. 46.1

C. 23.2

D. 29.5

No answer:

A. 1.9

B. 1.6

C. 1.7

D. 4.5

Q. If you chose “Yes,” what did you do? (Multiple answers allowed.)

Told my children/grandchildren:

A. 76.6

B. 82.0

C. 75.0

D. 65.5

Wrote about my experience in a memoir:

A. 17.4

B. 6.0

C. 22.1

D. 34.5

Drew pictures based on my memories:

A. 1.5

B. 2.0

C. 0.0

D. 6.9

Shared my account at survivors’ meetings or peace gatherings:

A. 18.5

B. 24.0

C. 15.4

D. 13.8

Was invited to schools or other venues to share my account:

A. 11.7

B. 6.0

C. 14.7

D. 17.2

Expressed my experience in poetry or other forms of art:

A. 3.4

B. 2.0

C. 5.1

D. 0.0

Other:

A. 32.5

B. 23.0

C. 39.7

D. 31.0

Q. If you chose “No,” choose from responses that are closest to your ideas. (Multiple answers allowed.)

It is impossible to tell my experience to others.

A. 22.4

B. 21.6

C. 26.2

D. 15.4

It is painful to remember.

A. 31.5

B. 33.0

C. 28.6

D. 30.8

Had no opportunities to share my experience.

A. 11.9

B. 5.7

C. 28.6

D. 0.0

Afraid of making myself/my family a target of discrimination.

A. 19.6

B. 26.1

C. 9.5

D. 7.7

Cannot find meaning in sharing my experience.

A. 14.7

B. 17.0

C. 9.5

D. 15.4

Other.

A. 22.4

B. 12.5

C. 23.8

D. 84.6

Q. Do you think the A-bomb experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have contributed to peace in the world and the prevention of nuclear war?

Yes.

A. 34.1

B. 26.7

C. 37.0

D. 54.5

To some degree.

A. 36.8

B. 42.9

C. 34.8

D. 18.2

Not very much.

A. 8.9

B. 3.1

C. 13.8

D. 13.6

No.

A. 3.6

B. 4.7

C. 2.8

D. 2.3

I don’t know.

A. 11.8

B. 16.2

C. 8.3

D. 6.8

No answer.

A. 4.8

B. 6.3

C. 3.3

D. 4.5

Q. Do you think that people in your country are aware of the damage caused by the atomic bombings and the actual conditions of the survivors?

To a large degree.

A. 8.2

B. 7.9

C. 8.3

D. 9.1

To some degree.

A. 34.1

B. 37.2

C. 33.1

D. 25.0

Not very much.

A. 37.7

B. 40.8

C. 35.4

D. 34.1

Hardly at all.

A. 15.6

B. 10.5

C. 19.3

D. 22.7

I don’t know.

A. 2.6

B. 2.1

C. 3.3

D. 2.3

No answer.

A. 1.7

B. 1.6

C. 0.6

D. 6.8

Q. If you chose “Not very much” or “Hardly at all,” why do you think this is the case? (Can choose up to three responses.)

Because survivors haven’t talked about their experiences due to fears of discrimination.

A. 18.9

B. 30.6

C. 9.1

D. 12.0

Because people aren’t willing to face the horrors of the atomic bombings.

A. 44.1

B. 23.5

C. 71.7

D. 16.0

Because the media aren’t interested and don’t cover this issue.

A. 53.2

B. 55.1

C. 55.6

D. 36.0

Because people aren’t taught about this in schools and textbooks don’t provide enough explanation about it.

A. 45.5

B. 49.0

C. 40.4

D. 52.0

Because there aren’t enough venues to share A-bomb experiences, like peace gatherings.

A. 27.0

B. 35.7

C. 21.2

D. 16.0

Other.

A. 9.0

B. 4.1

C. 9.1

D. 28.0

Q. What method do you think is effective in conveying A-bomb experiences? (Can choose up to three responses.)

Children and grandchildren of survivors should hand down their memories.

A. 32.2

B. 36.6

C. 29.3

D. 25.0

Train people who are interested in the A-bomb experiences, other than family members of the survivors, to hand down these accounts.

A. 13.7

B. 19.4

C. 10.5

D. 2.3

Enhance peace education in schools.

A. 44.5

B. 44.0

C. 48.6

D. 29.5

People who experienced the war directly should strengthen their efforts to share their accounts.

A. 17.1

B. 21.5

C. 12.2

D. 18.2

Promote the peace movement, including a drive to ban atomic and hydrogen weapons.

A. 24.8

B. 30.4

C. 21.0

D. 15.9

Enrich the collections of A-bomb materials at museums and make good use of them.

A. 33.9

B. 38.7

C. 34.3

D. 11.4

Create more works of art on the atomic bombings, including films and literature.

A. 26.2

B. 24.6

C. 30.4

D. 15.9

Tell about A-bomb experiences in the situations of daily life.

A. 17.3

B. 10.5

C. 22.1

D. 27.3

Other.

A. 1.2

B. 2.1

C. 0.6

D. 0.0

I don’t know.

A. 5.0

B. 1.0

C. 7.2

D. 13.6

Q. How has your health been in the past year?

Good.

A. 12.7

B. 0.5

C. 22.7

D. 25.0

Not bad.

A. 37.3

B. 18.3

C. 54.1

D. 50.0

Prone to illness.

A. 44.5

B. 74.3

C. 18.2

D. 22.7

Bedridden.

A. 2.4

B. 4.7

C. 0.6

D. 0.0

No answer.

A. 3.1

B. 2.1

C. 4.4

D. 2.3

Q. Since the atomic bombing, have you been seriously ill and had to be hospitalized or see a doctor regularly for an extended period of time? (Exclude injuries resulting from traffic accidents or other accidents.)

Yes.

A. 50.5

B. 61.8

C. 42.0

D. 36.4

No.

A. 42.5

B. 30.4

C. 51.9

D. 56.8

No answer.

A. 7.0

B. 7.9

C. 6.1

D. 6.8

Q. If you chose “Yes,” do you think your illness is related to the atomic bombing?

Yes.

A. 60.4

B. 74.4

C. 55.3

D. 50.0

No.

A. 5.7

B. 5.1

C. 7.9

D. 6.3

I do not know.

A. 26.0

B. 20.5

C. 36.8

D. 43.8

No answer.

A. 7.9

B. 7.9

C. 6.1

D. 6.8

Q. Do you still think back to the atomic bombing and struggle with a strong sense of anxiety?

Often.

A. 8.9

B. 9.9

C. 5.5

D. 18.2

Sometimes.

A. 35.8

B. 49.2

C. 26.5

D. 15.9

Seldom.

A. 23.1

B. 20.4

C. 30.4

D. 4.5

No.

A. 25.2

B. 14.1

C. 30.4

D. 52.3

No answer.

A. 7.0

B. 6.3

C. 7.2

D. 9.1

Q. What do you think of Japan’s relief measures for survivors living overseas?

Sufficient.

A. 12.3

B. 3.7

C. 17.7

D. 27.3

Commendable to some degree.

A. 42.8

B. 37.7

C. 47.0

D. 47.7

Not enough.

A. 38.7

B. 55.0

C. 26.5

D. 18.2

No answer.

A. 6.3

B. 3.7

C. 8.8

D. 6.8

Q. If you chose “Commendable to some degree” or “Not enough,” indicate why you are dissatisfied. (Can choose up to three responses.)

There is an upper limit to the medical allowance.

A. 42.8

B. 36.2

C. 48.1

D. 58.6

The level of support is too low to begin with.

A. 44.2

B. 53.7

C. 33.1

D. 37.9

The system of support wasn’t established early enough.

A. 29.5

B. 24.3

C. 36.1

D. 31.0

Information on available support isn’t easy to obtain.

A. 13.0

B. 10.7

C. 15.8

D. 13.8

The application procedure for support is too complicated.

A. 28.3

B. 21.5

C. 38.3

D. 24.1

Other.

A. 8.3

B. 3.4

C. 12.8

D. 17.2

Q. Choose the responses that are closest to your ideas about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (Can choose up to three responses.)

Atomic bombs should not have been dropped for any reason.

A. 69.2

B. 74.9

C. 65.2

D. 61.4

Inhumane and unforgivable.

A. 35.6

B. 38.7

C. 29.3

D. 47.7

Japan’s surrender was obvious and there was no need to drop atomic bombs.

A. 30.3

B. 11.0

C. 47.5

D. 43.2

The bombings took place in a time of war and were unavoidable.

A. 9.6

B. 9.9

C. 9.4

D. 9.1

The bombings helped end the war sooner and brought about peace.

A. 28.4

B. 36.1

C. 22.7

D. 18.2

The bombings were the result of a war that Japan started.

A. 29.6

B. 42.9

C. 19.9

D. 11.4

I don’t know.

A. 4.3

B. 5.2

C. 4.4

D. 0.0

Other.

A. 1.9

B. 1.0

C. 2.8

D. 2.3

Q. Do you think nuclear weapons can be eliminated from the world in the near future?

Yes.

A. 9.6

B. 8.9

C. 9.9

D. 11.4

No.

A. 61.1

B. 66.0

C. 56.4

D. 59.1

I don’t know.

A. 24.3

B. 22.0

C. 27.6

D. 20.5

No answer.

A. 5.0

B. 3.1

C. 6.1

D. 9.1

(Originally published on April 11, 2015)

Survivors hope A-bomb experiences will be handed down

A survey of A-bomb survivors living in South Korea, North America, and South America has been carried out, timed for the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings. The results show how survivors overseas have been making efforts to convey their experiences and how they have suffered distress in the midst of social environments that are different from conditions in Japan. In addition to conducting the survey, the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed eight Hiroshima A-bomb survivors, mainly the leaders of survivors’ movements in different countries. This article explores what survivors living overseas think of their experiences, how they hope their memories will be handed down, and what requests they have regarding support for survivors.

Today, there are still a large number of nuclear weapons in the world. To prevent another tragedy like Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is vital that the A-bomb accounts of the survivors’ experiences be shared throughout the world and handed down to the next generation.

But the survey results show that survivors living overseas lack opportunities to share their experiences in public settings. Unlike survivors in Japan, in many cases their experiences are shared only between them and their children or grandchildren, and are not often conveyed to a larger groups of people. To the question “Do you think that people in your country are aware of the damage caused by the atomic bombings and the actual conditions of the survivors?”, 53.3 percent of the respondents answered either “Not very much” or “Hardly at all.”

The reasons vary by region. In North America (the United States and Canada), more than 70 percent of the respondents chose “Because people aren’t willing to face the horrors of the atomic bombings.” (Multiple answers were allowed.) This contrasts sharply with 16.0 percent in South America and 23.5 percent in South Korea. To view the atomic bombings in a positive light, the American public tends to neglect inconvenient facts. This suggests the conflicted feelings held by survivors living in the United States. In South Korea, “Because survivors haven’t talked about their experiences due to fears of discrimination” was chosen by 30.6 percent of the respondents, which is more than double the percentages in North and South America.

Still, many survivors believe that the appeals from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have a universal significance. Asked whether the experiences of the atomic bombings have had an impact on peace in the world or the prevention of nuclear warfare, a total of 70.9 percent of the respondents chose either “Yes” or “To some degree.” This can be interpreted as a sign that they are all the more aware of the importance of their experiences amid conditions different from those in Japan.

Survivors were also asked to freely describe their hopes for young people. “I hope to see Korean youth leading efforts to prevent nuclear war by working together with young people around the world.” (Man in his 70s, South Korea) “There are many young people who are against nuclear weapons, though they don’t have detailed knowledge about the actual state of the survivors. I hope that they, as the world’s conscience, will continue to raise their voices against nuclear weapons.” (Man in his 70s, Canada) Their comments reveal the survivors’ earnest desire that the younger generation will advance closer to a world without nuclear weapons than their generation could.

Aspirations for peace despite painful gap in support

Majority absolutely reject nuclear weapons

Responses to a question concerning the rights and wrongs of the atomic bombings show that the majority of the survivors absolutely reject nuclear weapons.

“Atomic bombs should not have been dropped for any reason,” which expresses the strongest rejection, was chosen by 69.2 percent of all respondents. (Multiple choices were allowed.) By region, 74.9 percent in South Korea, 65.2 percent in North America, and 61.4 in South America selected this response, close to the figure of 73.7 percent in Japan. These results convey the true feelings of survivors who directly experienced the event. Percentages of those who chose “The bombings took place in a time of war and were unavoidable” held at the nine percent level in all three regions.

On the other hand, the percentages of people who chose “The bombings were the result of a war that Japan started” varied greatly by region. In South Korea, 42.9 percent chose this response, while the figures were 19.9 percent in North America and 11.4 percent in South America.

The high percentage recorded in South Korea can be attributed to resentment felt against Japan’s long colonial rule before the atomic bombings. In North America, there was a much lower figure of 18.2 percent among U.S. respondents. Public opinion in the United States may be similar to this choice because of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. But the low percentage could reflect the A-bomb survivors’ unexpressed discontent with such public opinion.

Another choice that revealed large regional differences was “Japan’s surrender was obvious and there was no need to drop the atomic bombs.” In North and South America, almost 50 percent of the respondents chose this response, like in Japan. But only 10 percent of South Korean survivors chose this response. Though all the respondents equally reject the atrocity of the nuclear attacks, this difference highlights the gap in perceptions of history leading up to the atomic bombings.

More than 60 percent hold gloomy prospects of nuclear abolition

The United States is a nuclear superpower. South Korea is in the midst of a prolonged truce with nuclear-armed North Korea. Living in conditions that are different than those in Japan, survivors overseas have come to recognize the great difficulty of abolishing nuclear arms.

Asked whether they think nuclear weapons can be eliminated from the world in the near future, 61.1 percent of the respondents answered “No,” which is slightly higher than the figure of 58.2 percent in Japan. By region, the figures are 66.0 percent in South Korea, 56.4 in North America, and 59.1 in South America. The percentage was notably high in South Korea, which neighbors North Korea, and beyond North Korea are China and Russia, both nuclear powers. At the same time, 9.6 percent of all respondents answered “Yes,” which is lower than Japan’s percentage of 13.0.

Nevertheless, people expressed strong hopes for nuclear abolition in a section where they could freely write comments. “Nuclear weapons, which are capable of wiping out mankind, must be eliminated from the earth. This is not a problem for the next generation. The political leaders of the world must solve this problem now through international cooperation.” (Man in his 70s, South Korea) Many called upon Japan to act as the nation which experienced the atomic bombings. “Japan should be more aware of and emphasize its responsibility as the nation that experienced the atomic bombings, more actively involved in conveying the horrors of nuclear warfare and appealing for world peace.” (Woman in her 70s, the United States)

The survey results show that 70 percent of survivors living outside Japan believe that the A-bomb experiences have contributed to preserving peace in the world and preventing nuclear war from breaking out. How can these experiences make even greater contributions across national borders and how can they be passed down to the next generation? The cooperation of survivors and citizens in Japan with the people of other nations will be put to the test.

Discontent remains regarding ceiling on relief benefits

In their comments, many expressed anxiety about their health and discontent with relief measures, which lag far behind those provided in Japan.

In particular, close to 80 percent of South Korean survivors describe themselves as “prone to illness” or “bedridden,” much higher than in North and South America or in Japan, where the percentage was 26.7. South Korea’s high percentage may have resulted from the large proportion of people who were directly exposed to the radiation of the atomic bomb close to the hypocenter and also from the fact that Korean survivors had only limited opportunities to receive medical treatment when they were younger.

Asked whether the atomic bombing has something to do with the diseases the survivors have developed, more than 50 percent responded “Yes” in North and South America and Japan, but the figure was 74.4 percent in South Korea. A similar pattern is seen in the responses to “Do you still think back to the atomic bombing and struggle with a strong sense of anxiety?”

Previously, the Japanese government provided support only to survivors living in Japan. Though the gap in relief between those living in Japan and abroad has slowly narrowed, people remain dissatisfied and are particularly concerned about subsidies for medical expenses.

In Japan, survivors are entitled to free medical treatment, but there has been a ceiling for subsidies given to A-bomb survivors living outside of Japan. Among those who said that they were dissatisfied, the percentages were 36.6 percent in South Korea, 48.1 in North America, and 58.6 in South America. (Multiple answers were allowed.)

The comments written by Korean survivors show that they consider this to be part of the compensation for damages caused during the war. Japan’s Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry raised the ceiling significantly last fiscal year.

--------------------

Interviews with A-bomb survivors living overseas

Returned to South Korea only to encounter Korean War

Lee Ilsu, 85, resident of Busan, South Korea

I can’t believe 70 years have already passed since the atomic bombing. The lives of our generation have been filled with war, World War II and then the Korean War. We didn’t receive enough education and were forced to work at factories or outdoors, and we lost people close to us…

The people who experienced the horrors of the atomic bombing understand this misery. I was in the Ozu area (in Minami Ward, Hiroshima) when the atomic bomb was dropped, but I survived. I saw many victims, their bodies covered with maggots. I hate atomic bombing. We must get rid of nuclear weapons.

I came back to Hapcheon, South Korea with my family in November 1945. It became the site of a hard-fought battle in the Korean War, which began in 1950. My mother lamented that it was even scarier than the atomic bombing, but she died soon after that. She had already been suffering from the aftereffects of the bombing in Hiroshima.

After returning to my country, I had a hard time for a little while because I couldn’t read Korean. I moved to Busan with my husband, and a branch office of the Korean Atomic Bomb Victim Association opened there. I helped with applications for benefits as I could understand Japanese.

Survivors residing outside of Japan lived without any support for a long time. Japanese citizens’ groups helped us file lawsuits, and finally we’re able to receive support. We’re not demanding any more support than the Japanese survivors receive. We just hope that the gap can be reduced between us and the Japanese survivors.

Gap still exists in medical care benefits

Sim Jintae, 72, resident of Hapcheon County, South Gyeongsang Province, South Korea

Support for survivors living overseas has lagged far behind the support for Japanese survivors. It was only in 2003 that the directive by the former Health and Welfare Ministry was repealed. The directive prevented survivors living outside Japan from receiving the benefits of medical treatment overseas. Survivors are survivors no matter where they live. All the survivors must be treated the same.

It is also a matter of post-war reparations. The Japanese government’s stance is that postwar compensation has been resolved with the Korea-Japan Claims Settlement Agreement, which was adopted 50 years ago. But as one of the Korean survivors who has been kept out of the loop, I don’t think the problem has been settled. In 2011, the Constitutional Court of Korea ruled that neglecting the issue of the right to seek damages is unconstitutional and demanded that the South Korean government address this problem. The governments of both countries must take responsibility for resolving this issue.

At the time of the atomic bombing, I was two years old and I was in Eba (in Naka Ward, Hiroshima). My family returned to Korea the following month, but my father was drawn into the Korean War and was killed in 1950.

It has become extremely hard for survivors living in Korea to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. People who were very young at the time and don’t have memories of the atomic bombing must rely on their parents’ testimonies. But if they missed the chance to ask their parents about what happened, it’s very hard to gather enough evidence, as required. At the Hapcheon branch of the Korea Atomic Bomb Victim Association, survey sheets from about 6,000 survivors are kept for safekeeping. These documents should be fully utilized in supporting the survivors.

Human rights, honor not restored

Won Jungboo, 74, resident of Seoul, South Korea

I wish I had known about the terrible effects of radiation from the atomic bomb earlier. Survivors who returned to South Korea couldn’t get enough information and were unable to receive adequate medical treatment. I think this situation hastened the deaths of many people.

I was at my house in Kamitenma-cho (in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima) with my mother, grandmother, and three brothers when the bomb exploded. We spent one week in our half-destroyed house. Because we heard that strange diseases were spreading, we moved to a mountainous area and returned to our country at the end of 1945. My mother and youngest brother were in our garden at the time of the bombing and were apparently exposed to a large amount of radiation. They died within a year or two. I’m doing well now but worry about my health.

Survivors living in South Korea are facing the problems of restoring our human rights and honor, which had been denied. We spent a long time without knowledge of the horrible effects of radiation from the atomic bomb. After the normalization of ties between South Korea and Japan in 1965, it became easier to gain information, but then we had to suffer from discrimination. This is a domestic problem in South Korea, but the prejudice is deeply rooted.

It’s unacceptable that there is a gap in relief measures between those living in Japan and those living abroad. The United States is responsible for the bombings, but Japan created the cause for Koreans to become A-bomb survivors, as many people were forced to work in Hiroshima or Nagasaki because of Japan’s colonial rule. As this year marks the 50th anniversary of the normalization of ties between the two countries, these past problems should be properly settled.

Support measures should meet the conditions of each country

Mariko Lindsey, 69, resident of Hercules, California, the United States

I was born in April 1946 and was still in my mother’s womb at the time of the atomic bombing. My mother was pregnant and encountered the explosion about 1.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. She was on her way from Otake to her assigned work, helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane. When she came to, she realized that her clothes had been blown off her body and the lunch box she was carrying had also been blown away, leaving only the handle.

After finishing high school in Hiroshima, I went by myself to the United States to study social welfare. I helped the Committee of A-bomb Survivors in the U.S.A., and my friends and I collected accounts of A-bomb survivors living in the United States. I started to think about my mother’s experience of the bombing. I was about 40 then.

My mother didn’t bring up the subject herself, and I know very little about her experience. I’m keenly aware that this is something I should have learned and conveyed to others.

The biggest problem survivors living in the United States face is the medical costs, which are often quite high. Medicare, which is a public health insurance program for the elderly, doesn’t cover these costs, so many survivors buy private health plans on their own. Now there’s a system to cover a portion of the medical costs, but you have to go through a cumbersome procedure. Many people hope their insurance premiums will be subsidized. It would be nice if we could choose from different options. The relief system should be made flexible to meet the needs of conditions in each country.

Many people don’t share their stories out of fear of discrimination

Junji Sarashina, 86, resident of Buena Park, California, the United States

It’s hard to hand down our experiences of the atomic bombing in the United States. There are many things that trouble us. Many of the survivors haven’t mentioned their experience out of fears like “My insurance policy might be canceled” or “There may be discrimination when it comes to the marriage prospects of family members.” I’m not sure whether my grandchildren’s generation understand the word “hibakusha.”

I belong to the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki A-Bomb Survivors (ASA). The ASA is facing financial difficulty, and the annual fees paid by members cover only postage. Our members are old, and the group’s survival will depend on the second generation.

I was born in Hawaii and moved to Hiroshima, where my parents were from, before the Pacific War broke out. When I was a third-year student at the former Hiroshima First Middle School, I experienced the atomic bombing at a factory in Kanon (in Nishi Ward). I helped cremate the bodies of many of my classmates.

After I went back to Hawaii, I was drafted to serve in the Korean War. Later I moved to California. Working for a Buddhist organization has given me emotional support. I appreciate the medical checkups and consultations provided by the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association. I’m filled with a special feeling of ease when I can talk with doctors using the Hiroshima dialect.

The path toward the elimination of nuclear weapons is a long uphill road. If the president of the United States were to declare that the whole nuclear arsenal would be dismantled, he or she would be immediately driven from office. However, despite all this, I believe politicians have the responsibility to move things forward.

The voices of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have power

Setsuko Thurlow, 83, resident of Toronto, Canada

I was 13 and working as a mobilized student at the Imperial Japanese Army’s Second General Headquarters in Futaba no Sato (in Higashi Ward, Hiroshima) when the A-bomb was dropped. I still remember the event clearly. Instead of telling only how horrible the bombing was, I hope to convey how the survivors rose from the ashes and how they have searched for meaning in their lives.

I moved to Canada in 1955 and have been sharing my A-bomb experience with others. While I was studying in the United States, a newspaper reporter asked me to comment on a U.S. hydrogen bomb test conducted at the Bikini Atoll. I made a critical remark, and I received anonymous letters that were threatening. I was scared, but this experience made me determined to make it my mission to tell the story of Hiroshima for the survival of the human race.

Handing down the A-bomb accounts is a difficult challenge. No one can really tell my experience for me, but people can convey our thoughts and vision based on their understanding of our experiences. I asked my son to give a speech at the “Hiroshima Day” peace gathering held in Toronto two years ago. I felt happy when he accepted the invitation, saying he felt honored. Maybe he’s aware of his identity as a second-generation hibakusha.

Even if you aren’t a hibakusha, your voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have power. To realize a world without nuclear weapons, each and every one of you should take your responsibility to heart and make efforts, especially, to move the Japanese government.

Winning better conditions through lawsuits

Mitsuo Tomozawa, 85, resident of Whittier, California, the United States

I experienced the atomic bombing in the Kasumi-cho area (in Minami Ward, Hiroshima) and was conscripted to serve in the Korean War, but I survived. When I learned that there are other A-bomb survivors in the United States, I thought God made me live to work for them and I’ve been involved in the survivors’ movement ever since. Now I’m active as a member of the North America A-Bomb Survivors Association.

There were different opinions among members, but I believe the discriminatory treatment toward survivors living outside Japan has been reduced through legal battles. We worked together with survivors in Brazil and South Korea, and with the help from lawyers in Hiroshima and others, we won these cases.

I’m a second-generation Japanese American and I was born in Hawaii. My parents wanted me to be educated in Japan, and sent me to Hiroshima when I was 10. Three years after the atomic bombing, I went back to Hawaii. I had lost most of my English and then I got drafted, so it took time to enter a higher-level school. I studied under adversity.

When I gave my account here, I always received telephone calls or letters the following day. The anonymous messages said, “Go back to Japan.” I’ve tried to convey my thoughts as a pacifist, but after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States, I sometimes feel that I’m just wasting my breath. But I still remember what happened when the bomb was dropped, as if it happened yesterday. I hope to help build a peaceful world for my children and grandchildren.

Atomic bombing pushed family into poverty

Junko Nakauchi, 70, resident of Sao Jose dos Campos, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Suffering from diabetes, kidney disease, and anemia at the same time, I spent two weeks in a hospital in Brazil last July. It cost 1.7 million yen. Unlike in Japan, we don’t have a good public health insurance system in Brazil. I found out that treatment undertaken right after taking out a private insurance policy isn’t covered by insurance. So I had to take out an eight-year loan at the bank to pay the medical bills.

I know that survivors can receive treatment without bearing the expense themselves if we travel to Japan. But I’ve been receiving dialysis treatment and can’t possibly go to Japan. There’s a subsidy program, but I’d like a system which covers medical costs, like in Japan. But if it takes time to implement such a system, it would be pointless.

I was only a year old and at my house in Senda-machi (in Naka Ward, Hiroshima) when the bomb was dropped. We were not well off, partly because my father was exposed to radiation from the bomb. About 10 years after the end of the war, he had health problems and was hospitalized. He used to run a taxi company, but he had to close his business. Several years after our family moved to Brazil, he became bedridden.

I was 15 when I came to Brazil. I did nothing but work on farms from morning to night to help provide for the family. As I couldn’t go to high school, I couldn’t get a better-paying job. The atomic bombing impacted not only the victims’ lives but also the lives of their children and grandchildren. I want people to know this.

--------------------

History of Korean suffering under Japan’s colonial rule

Interview with Noriyuki Kawano, professor at the Institute for Peace Science at Hiroshima University

What can we learn from the results of the survey?

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Noriyuki Kawano, professor at the Institute for Peace Science at Hiroshima University, who has interviewed many A-bomb survivors living overseas and victims of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident in the former Soviet Union.