1. Radiation: A threat to a Way of Life

Jan. 25, 2013

Chapter 2: Soviet Union

Part 3: The Spread of Nuclear Contamination over Sweden

Part 3: The Spread of Nuclear Contamination over Sweden

The fallout from Chernobyl not only caused widespread contamination of the Soviet Union, but, carried by the wind, it also affected vast areas of Europe. Across the Baltic Sea in Sweden, radiation has brought destruction on a huge scale to the home of the nomadic Lapps, who live by following the herds of reindeer which roam the plains of Lapland, and has seriously affected dairy-farming regions in the center of the country.

1. Radiation: A threat to a Way of Life

The aftereffects of being in the path of the fallout were still painfully in evidence when we visited Sweden three years after the Chernobyl disaster. We met Per Anders Blind and his wife Anna, resting from a long and arduous journey, at their summer home in the village of Klimpfjäll in the highlands near the Norwegian border. They had followed the reindeer herds for 125 miles across the plains of Swedish Lapland, which were just beginning to thaw after the winter.

"Of the eight hundred head or so of reindeer that we managed to process last year, only sixteen were approved for human consumption. All the others had to be either used for mink feed or disposed of completely." She shrugged resignedly. It was the middle of May; the village was still covered in a layer of sparkling snow, the lake frozen over. "It's hard to believe that somewhere as beautiful as this could be contaminated by radiation," she said.

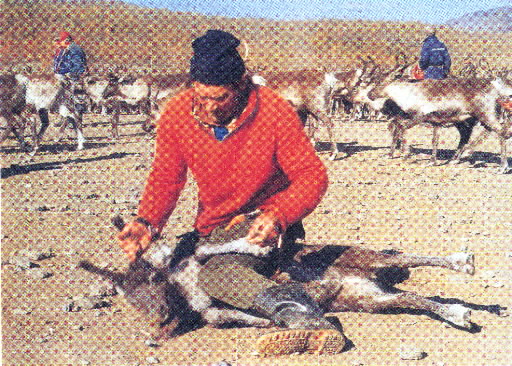

Reindeer breed in fall and calves are born in May and June, during which time they are left on their own in the mountains. In July, the reindeer are tagged according to owner, and in August and September they are herded into one area and the required number are slaughtered and processed for meat. At the start of winter the remainders are herded into the forests on the plains. This pattern has not changed over the years; the Lapps have coexisted with nature for centuries. However, their native Lapland has now become contaminated by radioactive substances that fell with the rain two days after the accident at Chernobyl. The soil around Klimpfjäll, one of the worst-affected regions in Sweden, was contaminated with cesium-137 at a level of 60,000 to 80,000 becquerels per square meter.

In the year following the accident, a total of 95,000 reindeer were processed for meat. Of these, 75,000 were found to contain levels of cesium-137 far above the safe level, which was defined at the time as 300 becquerels per kilogram of meat. The government disposed of these carcasses and handed out compensation to the owners.

The Swedish government, finding itself faced with a crippling financial burden, decided to ease the restrictions on a number of food items such as wild strawberries, mushrooms, reindeer and moose meat, and freshwater fish. The safe level of cesium-137 was raised to 1,500 becquerels. However, since 1986, reindeer meat, and fish caught in lakes in Lapland continue to show levels of up to 50,000 becquerels, and moose meat consistently registers levels of 5,000 becquerels per kilogram. The half-life of cesium-137 is relatively long: thirty years. Consequently, the effects on the animals of grazing on contaminated grass and moss may be expected to continue for some time yet.

The Blinds seem resigned to living with the effects of radiation: "Even if we're affected by contamination for the next ten or twenty years, it is too late to change our life-style," Per Anders told us. While the Blinds had decided that they would try and maintain the nomadic life-style they had followed all their lives, the younger generation were aware that it would not be so easy.

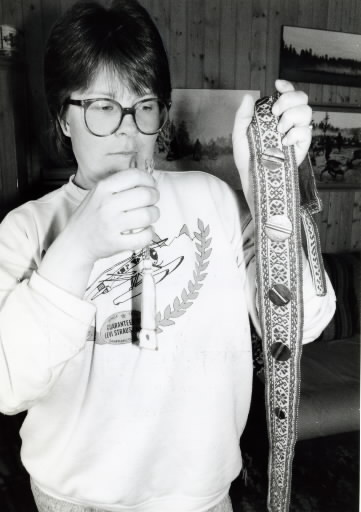

"We'd all have nervous breakdowns if we did nothing but think about the radiation all the time," said Åsa Baer, whom we met at the Blinds' house. Åsa and the Blinds' eldest son, Per Bjorn, were living close to the Blinds and carrying on the traditional Lapp life-style of herding reindeer. "Two years ago," she continued, "I had a test for cesium, and they found I had a level of ten thousand. But I haven't bothered since then."

Åsa told us that they are trying to forget about the contamination. However, when the killing season of August and September comes around, they cannot help but be reminded of it; in 1988 they again had to dispose of most of their reindeer meat because it did not meet the safe level, which by this time had been raised to 1,500 becquerels per kilogram. "We get compensation from the government for the contaminated meat, so there's no worry on that score," she continued, "but it seems such a waste to throw it out, it makes us wonder what we're bothering to work for."

Åsa is, however, adamant about her choice to lead the same life as her ancestors before her. "I'm not afraid of something that I can't detect with any of my senses. I love Lapland, it is the place where I was born and raised, and it's so beautiful, how could I leave it?"

Even though the number of young people who can speak the Lapp language is decreasing year by year, Åsa and Per Bjorn, as well as his brother Yon-Olov, are as fluent in Lapp as they are in Swedish, and they also have a good command of English. Thanks to modern technology, the Lapps are able to keep up with the news in the outside world, and they are well aware of the destruction of the earth's environment.

Life is much easier for Lapp youth than when their parents herded reindeer over one hundred miles with only skis and their legs to carry them—nowadays Japanese snowmobiles and motorbikes are used. Even so the number of young Lapps making a living out of herding reindeer is gradually decreasing, and the accident at Chernobyl has accelerated this trend. Summing up the feelings of the Lapps of his generation, Yon-Olov said, "When you realize that the cesium contamination is going to continue for the next twenty or thirty years, you can understand why young people find it difficult to commit themselves wholeheartedly to the traditional way of life. Plus there's no guarantee that the same type of accident won't occur again."

The Chernobyl disaster has made Lapp youth uncertain about the future of the traditional life-style in a way that would have been unthinkable five years ago. If their way of life is destroyed, the consequences for Lapp culture will be disastrous. The young people hold the key to the future, but at the moment they are wary about committing themselves to the Lapp life-style.

Baer's concern about the future of Lapp tradition is combined with uncertainty about the effects on her health of the radiation which has built up in her body. Both she and Per Bjorn would like children, but the thought of the possible effects of exposure to a high dose of radiation is always at the back of their minds.