2. The Unknown Victims of Radiation

Feb. 21, 2013

Chapter 4: India, Malaysia, Korea

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

Part 1: Living in the Shadow of Indian Nuclear Development

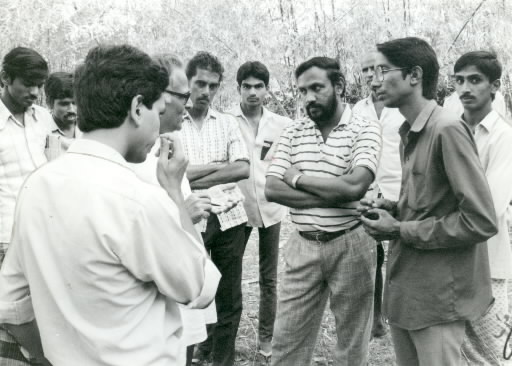

We visited Dr. Pramod Patil, whose practice is located in the town of Palghar, seven miles from Tarapur. A collection of medical equipment, including an ancient X-ray machine, was crammed into his tiny clinic. Dr. Patil told us about two patients he had treated a year previously.

"The moment I saw those two, I knew they were suffering from radiation sickness." The men had arrived at his clinic covered in red spots and suffering from diarrhea. They were migrant laborers who had traveled to Tarapur to work for a subcontractor there.

"I tried to get some more details about their illness, but we just couldn't understand each other," the doctor continued. After examining the men, Patil asked them to return later. He never saw them again. Including sixteen official languages and a plethora of local dialects, there are over three hundred languages in everyday use in India. The workers who are most likely to be exposed to radiation are those brought up by agencies from states in the south, such as Kerala.

"Not being able to speak the local language means they can't divulge information about their experiences," Dr. Patil said with a shrug. We were told that workers are sent back home at once if they do receive a large dose of radiation, and that no official record of their ever being at Tarapur exists, let alone the fact that they were exposed to radiation.

These laborers are told nothing about radiation; most don't even know the meaning of the word. If they do succumb to radiation-related diseases in later years, neither they nor their families will ever know the cause.

Killigudi Jayaraman, nuclear physicist and science editor for the news agency Press Trust of India, estimates that at least three hundred workers at Tarapur have been exposed to levels of radiation far higher than the 5 rems per annum allowed by regulation. On March 14, 1980, for example, cooling water leaked from the No. 1 reactor, and the twenty-six workers engaged in repairs were suddenly rushed to hospital in Bombay.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi took a dim view of the incident, and two high-ranking officials from the Department of Atomic Energy were summoned to New Delhi and reprimanded.

At first the Department of Atomic Energy refused to acknowledge the accident to the media. However, when the issue was raised in parliament, it had no choice but to admit to the accident.

"They acknowledged that there had been a pinhole in the reactor, but accused the media of blowing things out of proportion," he continued. "They're like this about everything, so there's no way anyone's going to find out how many laborers have been exposed to radiation."

In the village of Akarpatti a simple placard tells the story of one man who for eighteen years was engaged in the maintenance of the reactors at Tarapur.

Agih Patil, aged 50. Died December 5, 1989, 9 p.m.

Rest in Peace

His son, Parasharm, aged twenty-two, had shaved his head in accordance with Hindu funeral custom. "The cause of death was heart attack, or so they said," said Dattatraya Patil on behalf of the man's son, who sat watching us silently. "He worked in that plant with no film badge on. No matter what they say the cause of death was, how can they be so sure that radiation had nothing to do with it?"

It seemed that the villagers, who have no means of proving their suspicions, had erected this memorial in a silent gesture of defiance.