5. Multiple Burdens

Feb. 27, 2013

Chapter 4: India, Malaysia, Korea

Part 2: Thorium Contamination in Malaysia

Part 2: Thorium Contamination in Malaysia

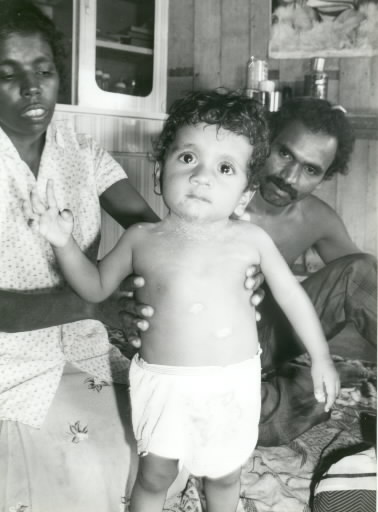

Kasturi was just over a year old, yet she could neither sit up by herself nor crawl. Her body was covered in a rash, part of her skull was missing, she had difficulty breathing and was mentally handicapped.

"I didn't really want to have Kasturi—it would've been better that way for her too," said Pancharvanam Shauniugam, cuddling her daughter. The doctor at Bukit Merah had recommended an abortion on the grounds that she had been exposed to radiation. Unfortunately for Pancharvanam, an abortion was beyond her means.

She and her husband, Chellan Muniandy, already had two daughters aged five and six. On her husband's income of between three and four hundred Malaysian dollars a month (approx. U.S.$115-$150) they had to not only support themselves but also help Chellan's parents, who lived by themselves. The two hundred dollars a month Pancharvanam had earned at a local lumber mill had been an essential source of income for the family. That lumber mill was next door to the ARE refinery.

Pancharvanam worked at the mill for approximately four years, from 1985 until she gave birth to Kasturi in 1988. She knew her workplace had abnormally high levels of radiation, thanks to the survey carried out by Professor Ichikawa, and had already had one abortion in February 1987. Unable to afford a second, she was forced to leave work to look after her disabled daughter.

The family was squatting in an empty house left by tin miners on the banks of the Serokai River three hundred yards from the ARE refinery. Until water pipes were put in two years previously, they had relied on a well for water. A large battery was providing power for a single light bulb and a black-and-white TV, on which the two older girls were disinterestedly watching an Indian program in Tamil.

"We really want to move for the sake of our two healthy daughters, but...," Chellan said, without enthusiasm.

Cheah Kok Leong is another of the children of Bukit Merah with multiple disabilities. Six years old, Kok Leong is deaf and cataracts have made him blind. He also has a hole in his heart, his bones are weak, and he is unable to support himself. His mother Lai Kwan had experienced no such difficulties with any of her eleven other children, the oldest of whom is twenty-eight. "I think it was because I worked on the extension of the ARE site while I was carrying him. I can't think what else it could be." She had just got home from her job as a day laborer on a construction site and was preparing dinner as she spoke to us.

Lai worked at ARE for just over a year, from the beginning of 1982 until February 1983. She gave birth to Kok Leong in April 1983. "There was this horrible smell at the site and I often used to get bad headaches. The supervisor was Japanese. He knew that I was pregnant but he never once warned me about radiation."

Lai's husband walked out on the family when Kok Leong was two years old. During the day the two junior high school age daughters take care of him while their mother goes out to work. Her monthly income is around two hundred Malaysian dollars (approx. U.S. $75). "With the help of the kids, we manage to make ends meet somehow."

In September 1988, Kok Leong had an operation on his left eye, enabling him to distinguish light from dark. He is also able to stand now. "If only I had enough money for a heart operation for him...," Lai Kwan remarked wistfully.

To these families for whom life itself is a daily struggle, the presence of a disabled child is an especially heavy burden.