8. Judgment Day Looming for Japanese Companies in Asia

Feb. 27, 2013

Chapter 4: India, Malaysia, Korea

Part 2: Thorium Contamination in Malaysia

Part 2: Thorium Contamination in Malaysia

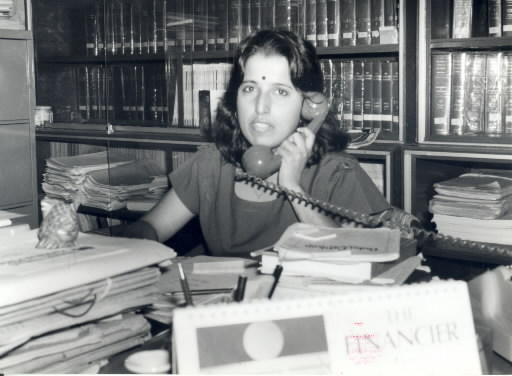

Lawyer Meenakshi Raman is one of those representing the people of Bukit Merah in their fight against ARE. When we visited her she was snowed under with meetings and the preparation of material for the case. Her office is on the island of Penang, in a stately white building reminiscent of colonial days. For the past eight years, Raman has been legal adviser to the Penang Consumers' Association, and has been involved with the ARE case since its initial stages in 1984. She sees the case as having important consequences for the health of all the people of Malaysia.

"I'll explain why ARE's operations are illegal," she began. "Firstly, ARE's actual operations are dangerous because of the radioactive gas, dust, and waste materials produced. Secondly, Mitsubishi Chemicals, which for all intents and purposes is the owner, while well aware of the danger of thorium, did not bother to construct even one storage facility."

This is the first time that radiation damage has been the subject of a court case in Malaysia. Raman herself had to study radiation from the basics. "Certainly it's a mammoth task to produce scientific proof for all our claims." Her efforts are not helped by the Malaysian government, which is pushing ARE's cause as part of its Look East policy, whereby states are encouraged to develop by learning from the examples of Japan and South Korea.

Raman and four of the citizens of Bukit Merah were arrested under the Internal Security Act, proclaimed one month after the case first appeared in court, in October 1987. To prove that radiation was responsible for the low white blood cell counts and the high incidence of miscarriages, the residents of Bukit Merah are relying on the results of the epidemiological survey. ARE manager Michael Wan, however, is confident that the decision will be in his company's favor.

"The level of natural background radiation is high in this area, although certainly not high enough to damage people's health. The locals and the academics are getting too emotional about the whole thing. I've heard," he added, "that their radiation readings were not accepted for the court records."

"If the ARE claims are correct, then the people here have very vivid imaginations," commented Raman indignantly. "Refineries like this in Japan stopped operating in 1972, so why are they allowed to carry out operations in Malaysia?"

The book Rare Earths, published by the Japan Society of Newer Metals, explains that refining was banned in Japan because there is a danger of contamination from thorium and uranium when rare earths are extracted from monazite. The book goes on to state that this is the main reason why monazite has not been imported into Japan since 1972.

Ironically, the general manager of ARE, Shigenobu Tamio, was one of the editors of this publication.

It is not surprising that Raman should ask us how Japan can carry out such an operation in Malaysia when it is considered too dangerous to do at home. "The lives of Japanese are more valuable perhaps..."

Mitsubishi Chemicals is the direct culprit in the case of Bukit Merah, but the real issue is a much wider one. It is not just one company that is being judged in the thorium contamination case. It is time for all Japanese businesses that operate in the international environment, the Japanese government, and ultimately the Japanese consumers, who enjoy the benefits of these operations, to face up to their responsibilities.