4. The French Cover-up in Corsica

Mar. 25, 2013

Chapter 5: Britain and France

Part 2: French Duplicity

Part 2: French Duplicity

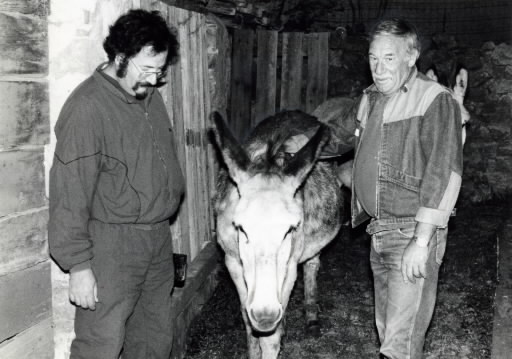

The battered car, which served as a mobile medical center, had definitely seen better days. As it wound its way slowly up the twisting Corsican mountain road, the driver, Dr. Denis Fauconnier, informed us over the din of the engine that in the next village on his rounds there was a large number of people suffering from thyroid conditions. According to the doctor these illnesses had been brought about by the accident at Chernobyl in 1986.

The village of Speloncato lies in the northwest of the island, three miles from the converted monastery that serves as Dr. Fauconnier's home and clinic. It has a population of 170. As we approached, we could see a group of stone houses clustered together around the top of the mountain. Responsible for providing health care in nine such villages, he makes regular visits to patients suffering from thyroid problems and has the complete trust of the residents.

The island of Corsica, approximately 2,250 square miles in area, has a population of 220,000. When it rained six days after the disaster at Chernobyl on May 2, 1986, the tourist paradise was covered in radioactive fallout. The news of contamination came not from the French government but via Italy.

"The government continued to insist that there had been no ill effects, even after the rain," the doctor said. "But when I called an Italian friend he told me that everyone was in a panic there because milk and vegetables had been contaminated. It really gave me a fright, I can tell you."

Fauconnier went round all the villages as fast as he could, warning people not to eat any vegetables or meat, or drink cows' or goats' milk. During that period the government was sticking to its "no negative effects" line in the newspapers and on television. However, as the doctor told us, "There was no reason why France should be safe when the rest of Europe was flying into a panic and taking all sorts of countermeasures." On May 12, exasperated by the government's attitude and wanting to know for certain the extent of the damage, he sent a sample of goats' milk to be analyzed by the Radiological Protection Board in Paris.

The results were just as he had expected. Iodine-131 was detected at a level of 4,400 becquerels per liter. The half-life of iodine-131 being eight days, he calculated that the level in Corsica on the day after the accident when it rained would have been 70,000 becquerels. "The EC level for safe consumption is set at 500 becquerels, so it was a hell of a shock when I heard the results." Disappointed with the government, which had not even bothered to carry out any kind of analysis until he sent the sample to Paris himself, Fauconnier continued his careful observation of the villagers' health. His fears were realized. In an area which already had a history of thyroid problems caused by viral infections, there was a sudden increase in the number of enlarged thyroid glands among children, and large numbers of the elderly also began to complain of sore throats. Thyroid problems increased threefold in the two years after Chernobyl.

Fauconnier was concerned that the next effect to make itself felt might be cancer, and with this in mind he wrote a letter to the authorities requesting a thorough medical survey of the local residents. The reply was simply a repetition of the well-worn phrase "there is no need to worry about radioactive contamination."

Fauconnier found it difficult to believe that the French government could be so indifferent to the issue of contamination. For the first time he realized just how heavily France relies on nuclear power. With fifty-three nuclear reactors, 69.9 percent of its power produced by atomic energy, and two out of every three homes running on nuclear-generated power, it was clear that the government was anxious to avoid any criticism of its own nuclear policies following from the accident at Chernobyl. For this reason, Fauconnier believes the government showed a marked lack of official interest in radioactive contamination, even to the extent of suppressing information.

It is just over two hundred years since the tricolor was raised to shouts of "liberty, fraternity, and equality." As far as nuclear policy is concerned, however, these ideals seem to have been lost along the way. "It's going to be some time before I can feel at all confident about the islanders' health," commented Dr. Fauconnier, as he got back into his car to continue his rounds.