5. Accuser of the Motherland

Mar. 25, 2013

Chapter 5: Britain and France

Part 2: French Duplicity

Part 2: French Duplicity

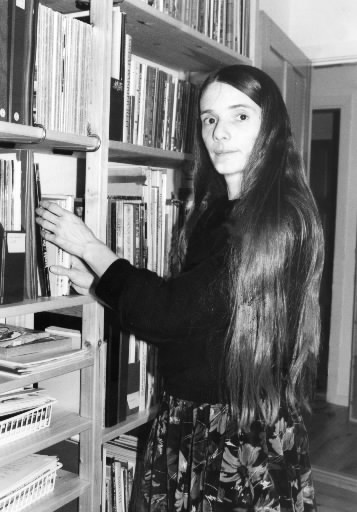

In Copenhagen, Denmark, we met a woman, Martine Petrod, whose father had worked at a nuclear weapons plant as well as at a bomb test site. Martine told us that her father had subsequently died of cancer. Although French by birth, Martine had taken up Danish citizenship ten years previously at the age of twenty-seven, and she now worked as an education consultant in Copenhagen. Her reason for giving up her French citizenship was, she told us, because she "couldn't stand the system there anymore."

Martine's father, René, became an electrician for the Atomic Energy Commission in 1966 and was employed at a nuclear weapons plant on the outskirts of Dijon, 185 miles southeast of Paris. It was during this period that France was forging ahead with its atmospheric testing program in defiance of world opinion. In 1966, the same year that René started work, the first nuclear test was carried out at Moruroa Atoll.

"My father's main job at the factory was general maintenance--one of his jobs involved installing electric safety devices," Martine told us. "I also heard that he sometimes had to work in the hot zone—that's the radioactive zone."

In 1972 Martine graduated from university and left for Denmark. In 1978 she was told that her father had cancer of the kidneys. "He was sent to Moruroa twice, once in 1977 and again in 1978. Soon after he got back the second time, he found out that he had cancer. He was fifty when he died." Martine's tone was unemotional.

Her father had received double pay while working at Moruroa and had enjoyed the added bonus of living in the South Pacific. Whenever he had any free time, he would go off snorkeling. Like the other French workers sent out to Moruroa, René had been told nothing of the dangers of radiation and the true nature of the work they were engaged in. When Martine first heard this from her mother, she started to change her attitude toward France.

"Well, wouldn't you?" she asked "Can you imagine allowing workers to swim in waters that you knew were contaminated with radioactive material from bomb tests? It just shows how ignorant and insensitive the French can be."

Martine's mother had heard about former colleagues of her husband's who had met a similar fate. "My mother is not the type who would get together with other families in the same situation and fight against the government for compensation and recognition," said Martine. "What's more worrying is that the vast majority of French people know next to nothing about the dangers of radiation."

She believes the media is to blame for this situation because of its tendency to turn a blind eye to criticism of the government's nuclear policy. The French media, she claims, is so caught up with vague notions of "national honor" and the image of France as the "policeman of Western Europe" that it has lost the ability to look objectively at nuclear issues.

Since her father's death she has acted on her own initiative helping those suffering from radiation-related illnesses. Using the FFr 150,000 (approx. US $27,000) compensation paid out to her as a surviving family member by the French government, she established the Copenhagen Foundation against Nuclear Tests.

Interest earned on this fund (between $2,000 and $3,000 per year) is sent directly to those victims most in need. Although she admits herself that it is not a great sum of money, Martine is happy to be able to do something to show her support for victims of radiation. In Denmark she has given lectures, spoken at rallies, written to newspapers, and generally done everything within her power to encourage public debate on France's nuclear policy. Largely as a result of her efforts, the island of Moruroa and French activities there have become well known among Danish people.

"It really is time for the French to wake up and face the facts. We shouldn't have to tolerate this 'see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil' attitude of the French media any longer."

In spite of the fact that Martine has changed her nationality, it would seem that she still feels a strong sense of duty to try to prevent further accidents involving radiation and to inform the public of France's irresponsible handling of radioactive substances.