4. Radon Checks Carried Out in Secret

Mar. 28, 2013

Chapter 6: Brazil and Namibia

Part 2: Namibia’s Uranium Mines

Part 2: Namibia’s Uranium Mines

The company town of Arandis lies seven miles to the north of the Rossing Mine. Workers began to move into accommodation there at the end of the 1970s, and at present it is home to nine hundred households with a total of more than 2,500 people. All the homes are detached and have a living room, three bedrooms, and a solar water heater providing a constant supply of hot water. The settlement has schools, a hospital, a church, and a supermarket, and it is surrounded by greenery, earning it the title of "the new oasis."

"It looks great, doesn't it?" remarked our guide, Hylton Villet, vice secretary of the MUN. "But actually it's only the unskilled black and Coloured workers who live here."

White workers and skilled black and Coloured workers are housed at the resort of Swakopmund, forty miles to the west on the Atlantic coast. "A lot of the residents of Arandis suffer from throat conditions caused by sulfuric gases from the mines. We've taken the issue up several times but to no avail; the company just keeps saying there is no problem. The environment at Swakopmund is clean, though; it's a textbook case of discrimination," he added, shaking his head irritably.

The greatest problem facing the residents of Arandis, which to the outsider appears to deserve its tide of "the new oasis," is that the town is located downwind from the mine and thus is constantly exposed to harmful substances released into the atmosphere during the mining and refining processes. Walking around the town, we came upon a number of odd plastic containers which turned out to be proof that the mine owners were worried about the possibility of harmful substances being emitted from the mine. We first encountered these when Paul Rooi, vice president of the MUN, took us to visit the home of a friend. The man was out, but his wife, Margaret, was happy to speak to us.

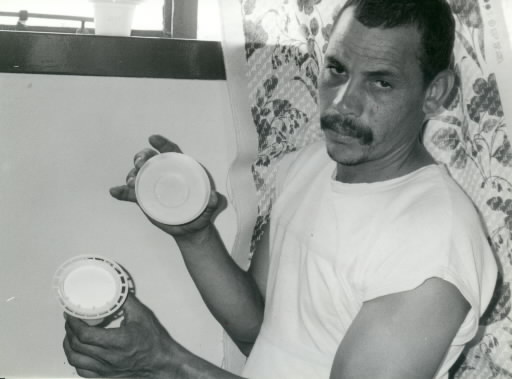

"What exactly is radon gas?" Her opening remark caught us off guard. Margaret told us that two employees from the mine had visited in November 1989, saying they wanted to check for radon gas. She showed us the two small plastic pots they had left behind. Shaped like inverted cones, they were about four inches high and inscribed with the numbers 989 and 990. We took off the lid of one to find a white paper filter inside. Radon, a radioactive gas, is produced from the decay of uranium-238 or thorium-232. The gas is released during mining, and radioactive particles attach themselves to the dust. When the dust is inhaled those particles are absorbed through the lung leading to an increased risk of lung cancer. Rooi and Villet were both surprised; neither of them had ever seen the pots before.

"I'm not sure, but it seems that the filter absorbs the radon," Margaret told them. "They come to change them sometimes, and I just do what they say."

The radon checks had begun with only a scant explanation about what they were for, and no information about the possible effects of exposure to radiation. There is no doubt the company discovered that radon gas was being released into the atmosphere and was trying to find out discreetly the seriousness of the contamination. "Is radon really that dangerous?" Margaret asked with a worried frown.