5. Mine Propaganda

Mar. 28, 2013

Chapter 6: Brazil and Namibia

Part 2: Namibia’s Uranium Mines

Part 2: Namibia’s Uranium Mines

During our stay at a hotel in the town of Swakopmund, where the white workers and black and Coloured skilled workers were housed, we noticed a poster advertising tours of the uranium mine. These operated every Friday and cost a mere five rand (approx. U.S. $2.50). At the time we were still waiting for a reply to our request for access to the mine to gather material, so we decided to take part in a tour to furnish ourselves with some extra background knowledge.

A few days later we arrived at the meeting point near the hotel at eight in the morning to find a group of fifty or so tourists had already gathered. Together with the sightseers, most of whom seemed to be German—perhaps not surprising considering Namibia was once a German colony—we climbed into a bus, emblazoned with the company slogan, Working for Namibia.

Fifty minutes later we arrived in the company town of Arandis, where our guide, Beth Volshenk, related the history of the Rossing Mine and its operations. However, no mention was made of the United Nations decree banning the export of Namibia's natural resources, or of the fact that Arandis was home to black and Coloured workers only.

After a brief drive around the town, we arrived at the mine itself just after ten o'clock, and were first taken to see the opencast pit, which was eight hundred feet deep and nearly a mile wide. We peered down into the pit, the sides of which were cut into terraces, and marveled at the machinery which from above looked more like toys. After only fifteen minutes walking around, our glasses were covered with a thin layer of powder. This was the dust the workers were so afraid of.

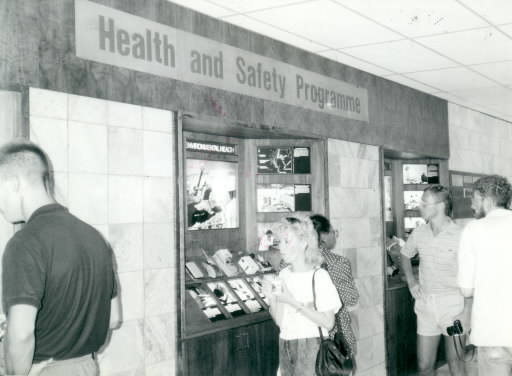

Our next stop was the plant where the ore is broken up to produce uranium oxide. During the tour the guide explained about levels of radiation at the mine, saying that the average level for workers at Rossing was 0.3 rems per year, well below the internationally designated safe exposure limit of 5 rems.

We had discovered that everyday hygiene standards were not being met, let alone radiation safety standards, so the figure of 0.3 rems hardly seemed credible. After completing the tour we asked some workers about this figure; without exception they replied they had never heard it before. The mine management was obviously doing its best to impress upon visitors how safe its operations were, but was less concerned about informing its employees.

"That's how they do things at Rossing," one of the workers commented wryly. "If we want to find out anything about radiation, it looks as though we'll have to join a tour as well."

A few days later, after much negotiation, we finally managed to meet Dr. Steve Kesler, the general manager of the mining operation. We quizzed him about the workers' radiation levels, the high incidence of respiratory diseases, and the measurement of radon gas in the town of Arandis, but his only reply was that the company was "doing its utmost for the welfare of the workers and their families." To our final question regarding the employees' concern about cancer, he answered confidently that there was no cause for concern about exposure to radiation, either at present or in the future.