Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima 75 years after the atomic bombing—Calling into question government’s obligations, Part 1: “Drawing a line” at providing benefits

May 19, 2020

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

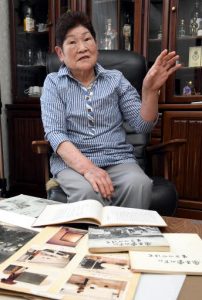

Whenever she comes across news related to atomic bomb survivors speaking to their experiences in newspapers or on television, Yoko Kubo, 81, a resident of the town of Kaita-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture, thinks, “I want people to know about victims like me.” Five members of her family were killed in the atomic bombing. But Ms. Kubo did not directly experience the atomic bombing and does not have an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.

Her home was located in the former Takajo-cho (now Honkawa-cho in Naka Ward) of Hiroshima. Her parents lived with their five children there and ran a needle factory. In the spring of 1945, when the situation surrounding World War II was growing dire, Ms. Kubo entered Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School). Before long, she and her brother, who was two years younger, evacuated to their uncle’s house in present-day Hatsukaichi for the sake of safety.

Feeling anxious about the children, her mother Sue Yamamoto, then 35, often visited them in Hatsukaichi. Early in the morning of August 6, Ms. Kubo saw her mother off at a nearby railroad crossing close to the train station. It was typical for her mother to leave for Hiroshima around 10:00 a.m., but on that day she left before her brother could wake, saying, “It tears me up inside when he cries and says he wants to come with me.” Ms. Kubo said, “Come back soon,” and her mother waved goodbye. That was the last time she saw her mother.

At 8:15 a.m., the atomic bomb was dropped. Their house in Hiroshima was about 600 meters from the hypocenter. The bones of her mother Sue and brother Tetsuji, then 1, were found among the burned ruins of the house. Ms. Kubo’s sister Kyoko, then 15, was also at home. She suffered severe burns over her entire body and died six days later. The bones of her father Kaname, then 45, and sister Yasuko, 13, have never been found. Yasuko was a second-year student at a girls’ high school and had been mobilized to help tear down buildings to create fire lanes.

Ms. Kubo fought back tears when she heard from her relatives how they searched for her family members where their house stood. “But I couldn’t contain my grief and cried aloud facing away, in the direction of the window.”

Ms. Kubo’s grandparents took on the role of their parents and looked after her and her brother. She was unable to return to the Takajo-cho district, and her grandfather opened a small needle factory, barely supporting the family, in the suburbs. Her grandmother had a bad lower back, and Ms. Kubo used to walk to a relatives’ vegetable shop to ask for food scraps that could not be sold.

Longing for her parents never abated

She always missed her parents. On a parent-visit day at her elementary school, she looked back when the classroom door opened behind her, imagining it was her mother. When someone told her that a woman who looked like her mother was seen at a train station, she went there to search for her. In job interviews, she was hurt when repeatedly asked why she did not have parents.

She managed to catch wind of a job and started work as a telephone switchboard operator. She became a member of a labor union and joined sit-ins in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the Peace Memorial Park staged to protest nuclear tests. In 1978, she was sent to the United States and conveyed her experience of losing her family in the atomic bombing in the country that dropped the bomb. She took part in the same kinds of activities that other A-bomb survivors did.

But when the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law was enacted at the end of 1994, she was made aware of a “line” regarding benefits she never could have imagined.

She heard that the national government would provide 100,000 yen as a “special funeral benefit” to all A-bomb victim’s families based on the law. She thought she would use the money to have a priest read a sutra for her five family members. However, it was learned that only those who possessed an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate could receive such money. She had also lost family because of the U.S. atomic bombing and the war the Japanese government had waged. “What’s the difference between them and me?” She was speechless.

The government said the benefits were designed to support living A-bomb victims. A-bomb survivors’ groups demanded the government provide condolence money to all the families of those killed in the atomic bombing as national reparations. Although the government proposed relief measures, it refused to regard them as national reparations. Its aim was to limit beneficiaries to “those who suffered special damage from radiation” and reduce the scope of relief measures so as to not include air-raid and other war victims.

“Deception” criticized

Even among Hiroshima’s A-bomb survivors who had the certificate, many saw through the government’s stated intentions and criticized its policy as “deception.”

A quarter of a century has passed since then. Ms. Kubo still feels distrust for the government’s divide-and-rule policy. Countless people, whether or not they were exposed to radiation, lost families and had to withstand hardships to make it through life. “It was not that I wanted money. I wanted the national government to take responsibility and face up to the terrible suffering caused by the atomic bombing and war.” Such is Ms. Kubo’s hope.

(Originally published on May 19, 2020)

Aid recipients must be survivors, but pain of losing families no different

Whenever she comes across news related to atomic bomb survivors speaking to their experiences in newspapers or on television, Yoko Kubo, 81, a resident of the town of Kaita-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture, thinks, “I want people to know about victims like me.” Five members of her family were killed in the atomic bombing. But Ms. Kubo did not directly experience the atomic bombing and does not have an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.

Her home was located in the former Takajo-cho (now Honkawa-cho in Naka Ward) of Hiroshima. Her parents lived with their five children there and ran a needle factory. In the spring of 1945, when the situation surrounding World War II was growing dire, Ms. Kubo entered Honkawa National School (now Honkawa Elementary School). Before long, she and her brother, who was two years younger, evacuated to their uncle’s house in present-day Hatsukaichi for the sake of safety.

Feeling anxious about the children, her mother Sue Yamamoto, then 35, often visited them in Hatsukaichi. Early in the morning of August 6, Ms. Kubo saw her mother off at a nearby railroad crossing close to the train station. It was typical for her mother to leave for Hiroshima around 10:00 a.m., but on that day she left before her brother could wake, saying, “It tears me up inside when he cries and says he wants to come with me.” Ms. Kubo said, “Come back soon,” and her mother waved goodbye. That was the last time she saw her mother.

At 8:15 a.m., the atomic bomb was dropped. Their house in Hiroshima was about 600 meters from the hypocenter. The bones of her mother Sue and brother Tetsuji, then 1, were found among the burned ruins of the house. Ms. Kubo’s sister Kyoko, then 15, was also at home. She suffered severe burns over her entire body and died six days later. The bones of her father Kaname, then 45, and sister Yasuko, 13, have never been found. Yasuko was a second-year student at a girls’ high school and had been mobilized to help tear down buildings to create fire lanes.

Ms. Kubo fought back tears when she heard from her relatives how they searched for her family members where their house stood. “But I couldn’t contain my grief and cried aloud facing away, in the direction of the window.”

Ms. Kubo’s grandparents took on the role of their parents and looked after her and her brother. She was unable to return to the Takajo-cho district, and her grandfather opened a small needle factory, barely supporting the family, in the suburbs. Her grandmother had a bad lower back, and Ms. Kubo used to walk to a relatives’ vegetable shop to ask for food scraps that could not be sold.

Longing for her parents never abated

She always missed her parents. On a parent-visit day at her elementary school, she looked back when the classroom door opened behind her, imagining it was her mother. When someone told her that a woman who looked like her mother was seen at a train station, she went there to search for her. In job interviews, she was hurt when repeatedly asked why she did not have parents.

She managed to catch wind of a job and started work as a telephone switchboard operator. She became a member of a labor union and joined sit-ins in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the Peace Memorial Park staged to protest nuclear tests. In 1978, she was sent to the United States and conveyed her experience of losing her family in the atomic bombing in the country that dropped the bomb. She took part in the same kinds of activities that other A-bomb survivors did.

But when the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law was enacted at the end of 1994, she was made aware of a “line” regarding benefits she never could have imagined.

She heard that the national government would provide 100,000 yen as a “special funeral benefit” to all A-bomb victim’s families based on the law. She thought she would use the money to have a priest read a sutra for her five family members. However, it was learned that only those who possessed an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate could receive such money. She had also lost family because of the U.S. atomic bombing and the war the Japanese government had waged. “What’s the difference between them and me?” She was speechless.

The government said the benefits were designed to support living A-bomb victims. A-bomb survivors’ groups demanded the government provide condolence money to all the families of those killed in the atomic bombing as national reparations. Although the government proposed relief measures, it refused to regard them as national reparations. Its aim was to limit beneficiaries to “those who suffered special damage from radiation” and reduce the scope of relief measures so as to not include air-raid and other war victims.

“Deception” criticized

Even among Hiroshima’s A-bomb survivors who had the certificate, many saw through the government’s stated intentions and criticized its policy as “deception.”

A quarter of a century has passed since then. Ms. Kubo still feels distrust for the government’s divide-and-rule policy. Countless people, whether or not they were exposed to radiation, lost families and had to withstand hardships to make it through life. “It was not that I wanted money. I wanted the national government to take responsibility and face up to the terrible suffering caused by the atomic bombing and war.” Such is Ms. Kubo’s hope.

(Originally published on May 19, 2020)