Seventy-five years after the atomic bombing—Survivors’ groups at crossroads, Part 4: Second-generation survivors

Jul. 28, 2020

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

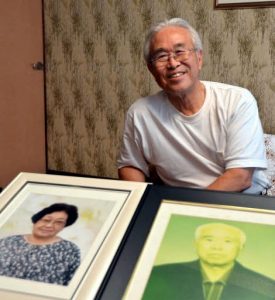

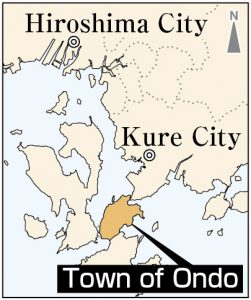

“Above all, second-generation survivors are children of A-bomb survivors,” said Kenji Sakimoto, 73, as he began to speak at his home in the town of Ondo, Kure City. As a second-generation survivor, he serves as president of an A-bomb survivors’ association in the town. His words sounded so obvious, we wanted to probe their meaning. “The most important thing as a child is to understand the parent survivors of the atomic bombing,” he replied.

Mr. Sakimoto’s father Jiro (who died in 2000 at the age of 82) was once president of the same association. When his successor and Mr. Sakimoto’s uncle, Shoji Ogata, 90, grew too elderly for the role, Mr. Sakimoto succeeded Shoji as president in 2019. There were about 560 members when the association was established in 1964, but that number has decreased to about 120. Mr. Sakimoto repeatedly asked himself what second-generation survivors, who did not experience the atomic bombings, can do for this cause.

A-bomb survivors are holding out hope for the second-generation to become a pillar of the A-bomb survivors’ movement. Some second-generation survivors have established their own organizations. Having feared that their health might have been affected by radiation from the atomic bombing, some call on the government to provide support from to the second-generation survivors.

The association currently has 40 members that are second-generation survivors, but many are still active in their careers, making it difficult for them to become involved in the movement. Mr. Sakimoto says, “I think it’s even more important to understand the lives of our parents than it is to be engaged in the movement. That’s our role.” He believes there are memories that only the second-generation can inherit from parents and convey to others.

Learned of father’s A-bombing experiences from memoir in association’s publication

Mr. Sakimoto was born in 1946, a year after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Both of his parents were A-bomb survivors. His father, a soldier working at the Army’s Marine Training Division in Ujina-machi (now part of Minami Ward, Hiroshima), was exposed to the atomic bombing on his way to work. His mother, Hanako, who died in 2018 at the age of 95, was at home in Ushita-machi (now part of Higashi Ward) on that day. She was sprayed by shards of glass at their home and badly wounded.

Jiro described horrible scenes at the training division, where many victims were housed after the bombing, in his memoir in a collection of association members’ A-bomb experiences published in 1985. “People were crying, calling for their parents, groaning—it was so terribly clamorous. No one would be able to understand this chaos without actually experiencing it,” read one of the descriptions. “I went to the front several times and saw so many people killed in action, but nothing was as awful as that scene. It’s incomparable.”

“My father never shared his A-bomb stories with others.” Mr. Sakimoto himself first learned the details of his father’s A-bombing experiences from the memoir. However, Jiro once told his son about his experience at the front in Rabaul, Papua New Guinea, which he described as being a failure to kill himself.

Jiro’s subordinates worked hard to protect him while he was in the throes of malaria amid vicious exchanges of fire at the front. Not wanting to allow them to die with him, Jiro put a rifle to his throat to kill himself but ultimately could not pull the trigger. “I could fire at the enemies without hesitation, but I could not kill myself,” he said in a strained voice as if blaming himself for having clung to life. Those words remain impressed in Mr. Sakimoto’s memory.

After Jiro returned alive from the southern islands, he experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. He survived by fortunately being behind a building and thereby escaped direct thermal rays that emanated from the bomb. After the war, he worked at a steelworks factory, and became president of the association in the waning years of his career. Mr. Sakimoto remembers his father as always being busy helping those who wanted to obtain an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, by looking for witnesses, writing documents, or negotiating with the prefectural government.

A memory only his son knows

Mr. Sakimoto has one unforgettable memory with his father. When he was a child, they were working in the fields that had been passed down in the family. During a break from work, they picked a large, crimson Japanese persimmon from one of the trees. They sat down and ate it together. “Kenji, there were many kinds of delicious fruit varieties in Rabaul, but none matched the taste of this persimmon.”

In autumn, Mr. Sakimoto still picks persimmons from the same tree, sits down at the same spot, and eats. The sweet flavor of the persimmon in his mouth contains the memories of his father, who narrowly returned alive from the war front and survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Such precious moments of an A-bomb survivor’s life are not introduced at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum or in any of the video recordings of A-bomb testimonies. It was a casual but precious moment in the life of an A-bomb survivor only his son knows.

“It is our responsibility to pass on our parents’ A-bomb experiences to our children and grandchildren.” Mr. Sakimoto hopes that other second-generation survivors can together fulfill this role.

(Originally published on July 28, 2020)

Responsibility is to understand our parents’ lives and pass their experiences to next generations

“Above all, second-generation survivors are children of A-bomb survivors,” said Kenji Sakimoto, 73, as he began to speak at his home in the town of Ondo, Kure City. As a second-generation survivor, he serves as president of an A-bomb survivors’ association in the town. His words sounded so obvious, we wanted to probe their meaning. “The most important thing as a child is to understand the parent survivors of the atomic bombing,” he replied.

Mr. Sakimoto’s father Jiro (who died in 2000 at the age of 82) was once president of the same association. When his successor and Mr. Sakimoto’s uncle, Shoji Ogata, 90, grew too elderly for the role, Mr. Sakimoto succeeded Shoji as president in 2019. There were about 560 members when the association was established in 1964, but that number has decreased to about 120. Mr. Sakimoto repeatedly asked himself what second-generation survivors, who did not experience the atomic bombings, can do for this cause.

A-bomb survivors are holding out hope for the second-generation to become a pillar of the A-bomb survivors’ movement. Some second-generation survivors have established their own organizations. Having feared that their health might have been affected by radiation from the atomic bombing, some call on the government to provide support from to the second-generation survivors.

The association currently has 40 members that are second-generation survivors, but many are still active in their careers, making it difficult for them to become involved in the movement. Mr. Sakimoto says, “I think it’s even more important to understand the lives of our parents than it is to be engaged in the movement. That’s our role.” He believes there are memories that only the second-generation can inherit from parents and convey to others.

Learned of father’s A-bombing experiences from memoir in association’s publication

Mr. Sakimoto was born in 1946, a year after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Both of his parents were A-bomb survivors. His father, a soldier working at the Army’s Marine Training Division in Ujina-machi (now part of Minami Ward, Hiroshima), was exposed to the atomic bombing on his way to work. His mother, Hanako, who died in 2018 at the age of 95, was at home in Ushita-machi (now part of Higashi Ward) on that day. She was sprayed by shards of glass at their home and badly wounded.

Jiro described horrible scenes at the training division, where many victims were housed after the bombing, in his memoir in a collection of association members’ A-bomb experiences published in 1985. “People were crying, calling for their parents, groaning—it was so terribly clamorous. No one would be able to understand this chaos without actually experiencing it,” read one of the descriptions. “I went to the front several times and saw so many people killed in action, but nothing was as awful as that scene. It’s incomparable.”

“My father never shared his A-bomb stories with others.” Mr. Sakimoto himself first learned the details of his father’s A-bombing experiences from the memoir. However, Jiro once told his son about his experience at the front in Rabaul, Papua New Guinea, which he described as being a failure to kill himself.

Jiro’s subordinates worked hard to protect him while he was in the throes of malaria amid vicious exchanges of fire at the front. Not wanting to allow them to die with him, Jiro put a rifle to his throat to kill himself but ultimately could not pull the trigger. “I could fire at the enemies without hesitation, but I could not kill myself,” he said in a strained voice as if blaming himself for having clung to life. Those words remain impressed in Mr. Sakimoto’s memory.

After Jiro returned alive from the southern islands, he experienced the atomic bombing in Hiroshima. He survived by fortunately being behind a building and thereby escaped direct thermal rays that emanated from the bomb. After the war, he worked at a steelworks factory, and became president of the association in the waning years of his career. Mr. Sakimoto remembers his father as always being busy helping those who wanted to obtain an Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, by looking for witnesses, writing documents, or negotiating with the prefectural government.

A memory only his son knows

Mr. Sakimoto has one unforgettable memory with his father. When he was a child, they were working in the fields that had been passed down in the family. During a break from work, they picked a large, crimson Japanese persimmon from one of the trees. They sat down and ate it together. “Kenji, there were many kinds of delicious fruit varieties in Rabaul, but none matched the taste of this persimmon.”

In autumn, Mr. Sakimoto still picks persimmons from the same tree, sits down at the same spot, and eats. The sweet flavor of the persimmon in his mouth contains the memories of his father, who narrowly returned alive from the war front and survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Such precious moments of an A-bomb survivor’s life are not introduced at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum or in any of the video recordings of A-bomb testimonies. It was a casual but precious moment in the life of an A-bomb survivor only his son knows.

“It is our responsibility to pass on our parents’ A-bomb experiences to our children and grandchildren.” Mr. Sakimoto hopes that other second-generation survivors can together fulfill this role.

(Originally published on July 28, 2020)