HICARE, providing support for victims of radiation exposure for 17 years

Mar. 20, 2008

by Keisuke Yoshihara, Staff Writer

“Let us make the best use of the medical expertise of Hiroshima accumulated by virtue of the sacrifice of the A-bomb victims.” The Hiroshima International Council for Health Care of the Radiation-Exposed (HICARE) was established with this noble aim in mind. In the 17 years since its founding, HICARE has been engaged in a range of efforts, including the provision of medical support for those exposed to radiation in the accidents at Chernobyl and at other nuclear facilities. For several years now, HICARE has expanded the scope of its activities and has become involved in supporting hibakusha (A-bomb survivors) living abroad. “HICARE is now in a period of transition,” says President Hiroo Dohi. This report examines the current state and challenges of HICARE, focusing on its main mission of accepting trainees and dispatching medical personnel.

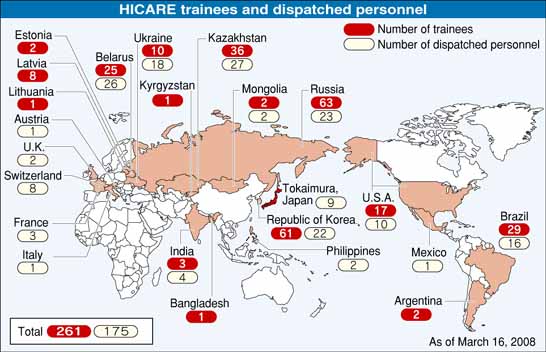

A total of 261 trainees accepted from 15 countries

“This is it,” agreed Lucy Akemi Matsumoto, a pediatric hematologist from Brazil, examining the dark cancer spot of a child with an MRI technique used to identify cancerous legions. Dr. Matsumoto was receiving training at Hiroshima University Hospital, the 261st trainee invited by HICARE.

She arrived in Hiroshima on February 28. At the university hospital, she observed the ambulatory care provided by doctors of the Pediatrics Ward headed by Dr. Hiroshi Kawaguchi. She also observed a bone-marrow transplant operation. Dr. Matsumoto will stay in Hiroshima until March 25 to continue her training in clinical techniques at various institutions, including the university hospital, Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, and the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council.

Since 1991, HICARE has been accepting physicians and other medical personnel for training from 15 countries, Russia and South Korea among them. According to a HICARE questionnaire completed in Kazakhstan in 2005 by 11 former trainees, the respondents indicated such benefits as “I can diagnose cancer and other diseases more easily than before” and “I found the screening method for gastric and breast cancer to be helpful.” As to the question “Was the training in Hiroshima useful for your current medical practice?”, seven people felt it was “very useful” and the other four agreed that it was “useful.”

Takeshi Yahata, a staff member of the HICARE secretariat who was involved in the survey in Kazakhstan, was pleased with the findings. He said, “Those who had received training were teaching their colleagues what they had learned, and in this way, the effect of the training was reaching a wider audience.”

But there are difficulties, too. For instance, in Brazil, doctors who took home techniques and technologies involved in providing care for those exposed to radiation are actively treating A-bomb survivors in their individual practices, but they don't yet enjoy an environment where they can collaborate and jointly conduct health examinations of these patients.

Toru Funaoka, HICARE staff in charge of trainees, said, “In Brazil, physicians don't develop the same kind of strong ties with other doctors as they do in Japan. And the former trainees are scattered widely in a very large country.” As hibakusha age, physicians who possess a deep understanding of these survivors' concerns and their specific symptoms are becoming increasingly important. Brazil is too far for Japanese doctors to visit frequently so training coordinators for the country is an urgent task. These coordinators would serve as a liaison between Brazil and Hiroshima and create a network of former trainees to enable physicians in Brazil to collaborate in conducting medical examinations.

Another issue involves the fact that the United States has a substantial number of hibakusha from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, about 970, but just a relative handful of trainees. Although the number of hibakusha is the second largest abroad, after South Korea, there have only been 17 trainees--just a quarter of the total in Russia--and none between 1998 and 2005. The duration of the HICARE training is generally from one to three months, and some argue that this is an unrealistic length of time to take leave from their workplaces. In order to address this concern, HICARE has initiated a shorter training program with a week-long format.

In fact, there are two types of hibakusha: A-bomb survivors, who are decreasing, as well as those newly exposed to radiation. In order to provide satisfactory medical care for both groups, what sort of trainees should be invited and how should they be trained? Hiroshima, as the base of support for the world's radiation sufferers, needs new wisdom to address these questions.

166 medical personnel have been dispatched overseas

HICARE has dispatched 166 medical personnel to 16 countries, including those dispatched to Kazakhstan, where nuclear test sites of the former Soviet Union were once located, to give technical guidance on medical examinations, and those dispatched to Russia to attend international conferences on the health issues of those engaged in the restoration work of the Chernobyl accident. In Japan, too, HICARE dispatched nine people, including physicians and radiological technicians, to Tokaimura, Ibaraki Prefecture in 1999, at the time of the criticality accident at the Tokaimura nuclear facility. This is in line with one of HICARE's priorities, to support emergency medical care.

In the past, medical personnel were dispatched mainly to provide technical guidance and medical support to local communities and to attend international conferences. Lately, though, other purposes have emerged, such as “verifying the practical effects of HICARE training” (Belarus, 2007), “promoting the establishment of a network between HICARE and its former trainees” (United States, 2006), and “studying the medical activities of the former trainees in Korea” (Republic of Korea, 2004). With HICARE's recognition that this is a period of transition for the organization, the number of activities related to project management have increased.

Nanao Kamada, who was the second President of HICARE and is now Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Hiroshima A-Bomb Survivors Relief Foundation, commends the achievements of the organization, saying, “HICARE, unfortunately, isn't well-known to the people of Hiroshima Prefecture, but residents should be proud of their efforts on behalf of the world's hibakusha by making use of the know-how gained through the tragic experience of Hiroshima.”

Dr. Kamada reports that new incidents involving potential radiation exposure are still occurring, such as the issue of imported stainless steel containing cobalt-60, a radioactive element, found in Italy this year. Under these circumstances, he says, HICARE will continue to play a crucial role.

Interview with Dr. Hiroo Dohi, President of HICARE

How would you assess HICARE's activities over the past 17 years?

HICARE began as an organization providing emergency medical care involving radiation exposure and, in this regard, we have visited all the key locations and invited medical personnel from these sites for training in Hiroshima. At this point, I think HICARE is experiencing a transition toward its next stage of work. In 2002, the Japanese government launched a support program for A-bomb survivors living abroad and HICARE responded by making assistance for these overseas hibakusha one of its new priorities. At the same time, we don't intend to shift our focus away from emergency medical care--we would like to advance both activities.

The Nagasaki Association for Hibakushas' Medical Care (NASHIM) was established in Nagasaki one year after HICARE. Some voices have called for more collaboration between HICARE and NASHIM.

HICARE and NASHIM have similar aims and activities. We haven't, however, discussed the specifics of a possible partnership. These details must first be discussed at working-level meetings of the two organizations.

What are HICARE's next steps?

In regard to our support for survivors overseas, we must promote more autonomous activities in the relevant countries. In addition, it's vital to disseminate information on radiation in order to prevent future nuclear accidents. In 1992, HICARE published a book, “Effects of A-bomb Radiation on the Human Body,” that comprehensively describes the research outcomes involving the medical care of hibakusha in Hiroshima. This book has become recognized widely as a standard reference in the field and we would like to update the data and issue a revised edition.

Keywords

HICARE

HICARE was established in April 1991 to provide support to victims of radiation exposure throughout the world by utilizing the expertise accumulated from the health care of A-bomb survivors and from various research activities on the health effects of radiation. The HICARE organization is composed of major medical institutions in Hiroshima Prefecture and operates on an annual budget, currently about 23 million yen, that is shared equally by Hiroshima Prefecture and Hiroshima City.

The Board of Directors includes the President of the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association, the President of the Hiroshima City Medical Association, the Director of Hiroshima University Hospital, the Chairman of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, and the President of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission.

HICARE's primary activities include:

1. inviting physicians, nurses, and medical researchers from overseas for training

2. dispatching physicians and other medical personnel to provide technical guidance and to attend international conferences

3. coordinating educational activities, such as lectures on radiation-related issues

The HICARE office is located at the Atomic Bomb Survivors Affairs Division of the Hiroshima Prefectural Government and eight staff members of the prefectural and the city governments are engaged in the secretariat work of HICARE along with their regular work assignments.

“Let us make the best use of the medical expertise of Hiroshima accumulated by virtue of the sacrifice of the A-bomb victims.” The Hiroshima International Council for Health Care of the Radiation-Exposed (HICARE) was established with this noble aim in mind. In the 17 years since its founding, HICARE has been engaged in a range of efforts, including the provision of medical support for those exposed to radiation in the accidents at Chernobyl and at other nuclear facilities. For several years now, HICARE has expanded the scope of its activities and has become involved in supporting hibakusha (A-bomb survivors) living abroad. “HICARE is now in a period of transition,” says President Hiroo Dohi. This report examines the current state and challenges of HICARE, focusing on its main mission of accepting trainees and dispatching medical personnel.

A total of 261 trainees accepted from 15 countries

“This is it,” agreed Lucy Akemi Matsumoto, a pediatric hematologist from Brazil, examining the dark cancer spot of a child with an MRI technique used to identify cancerous legions. Dr. Matsumoto was receiving training at Hiroshima University Hospital, the 261st trainee invited by HICARE.

She arrived in Hiroshima on February 28. At the university hospital, she observed the ambulatory care provided by doctors of the Pediatrics Ward headed by Dr. Hiroshi Kawaguchi. She also observed a bone-marrow transplant operation. Dr. Matsumoto will stay in Hiroshima until March 25 to continue her training in clinical techniques at various institutions, including the university hospital, Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, and the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council.

Since 1991, HICARE has been accepting physicians and other medical personnel for training from 15 countries, Russia and South Korea among them. According to a HICARE questionnaire completed in Kazakhstan in 2005 by 11 former trainees, the respondents indicated such benefits as “I can diagnose cancer and other diseases more easily than before” and “I found the screening method for gastric and breast cancer to be helpful.” As to the question “Was the training in Hiroshima useful for your current medical practice?”, seven people felt it was “very useful” and the other four agreed that it was “useful.”

Takeshi Yahata, a staff member of the HICARE secretariat who was involved in the survey in Kazakhstan, was pleased with the findings. He said, “Those who had received training were teaching their colleagues what they had learned, and in this way, the effect of the training was reaching a wider audience.”

But there are difficulties, too. For instance, in Brazil, doctors who took home techniques and technologies involved in providing care for those exposed to radiation are actively treating A-bomb survivors in their individual practices, but they don't yet enjoy an environment where they can collaborate and jointly conduct health examinations of these patients.

Toru Funaoka, HICARE staff in charge of trainees, said, “In Brazil, physicians don't develop the same kind of strong ties with other doctors as they do in Japan. And the former trainees are scattered widely in a very large country.” As hibakusha age, physicians who possess a deep understanding of these survivors' concerns and their specific symptoms are becoming increasingly important. Brazil is too far for Japanese doctors to visit frequently so training coordinators for the country is an urgent task. These coordinators would serve as a liaison between Brazil and Hiroshima and create a network of former trainees to enable physicians in Brazil to collaborate in conducting medical examinations.

Another issue involves the fact that the United States has a substantial number of hibakusha from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, about 970, but just a relative handful of trainees. Although the number of hibakusha is the second largest abroad, after South Korea, there have only been 17 trainees--just a quarter of the total in Russia--and none between 1998 and 2005. The duration of the HICARE training is generally from one to three months, and some argue that this is an unrealistic length of time to take leave from their workplaces. In order to address this concern, HICARE has initiated a shorter training program with a week-long format.

In fact, there are two types of hibakusha: A-bomb survivors, who are decreasing, as well as those newly exposed to radiation. In order to provide satisfactory medical care for both groups, what sort of trainees should be invited and how should they be trained? Hiroshima, as the base of support for the world's radiation sufferers, needs new wisdom to address these questions.

166 medical personnel have been dispatched overseas

HICARE has dispatched 166 medical personnel to 16 countries, including those dispatched to Kazakhstan, where nuclear test sites of the former Soviet Union were once located, to give technical guidance on medical examinations, and those dispatched to Russia to attend international conferences on the health issues of those engaged in the restoration work of the Chernobyl accident. In Japan, too, HICARE dispatched nine people, including physicians and radiological technicians, to Tokaimura, Ibaraki Prefecture in 1999, at the time of the criticality accident at the Tokaimura nuclear facility. This is in line with one of HICARE's priorities, to support emergency medical care.

In the past, medical personnel were dispatched mainly to provide technical guidance and medical support to local communities and to attend international conferences. Lately, though, other purposes have emerged, such as “verifying the practical effects of HICARE training” (Belarus, 2007), “promoting the establishment of a network between HICARE and its former trainees” (United States, 2006), and “studying the medical activities of the former trainees in Korea” (Republic of Korea, 2004). With HICARE's recognition that this is a period of transition for the organization, the number of activities related to project management have increased.

Nanao Kamada, who was the second President of HICARE and is now Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Hiroshima A-Bomb Survivors Relief Foundation, commends the achievements of the organization, saying, “HICARE, unfortunately, isn't well-known to the people of Hiroshima Prefecture, but residents should be proud of their efforts on behalf of the world's hibakusha by making use of the know-how gained through the tragic experience of Hiroshima.”

Dr. Kamada reports that new incidents involving potential radiation exposure are still occurring, such as the issue of imported stainless steel containing cobalt-60, a radioactive element, found in Italy this year. Under these circumstances, he says, HICARE will continue to play a crucial role.

Interview with Dr. Hiroo Dohi, President of HICARE

How would you assess HICARE's activities over the past 17 years?

HICARE began as an organization providing emergency medical care involving radiation exposure and, in this regard, we have visited all the key locations and invited medical personnel from these sites for training in Hiroshima. At this point, I think HICARE is experiencing a transition toward its next stage of work. In 2002, the Japanese government launched a support program for A-bomb survivors living abroad and HICARE responded by making assistance for these overseas hibakusha one of its new priorities. At the same time, we don't intend to shift our focus away from emergency medical care--we would like to advance both activities.

The Nagasaki Association for Hibakushas' Medical Care (NASHIM) was established in Nagasaki one year after HICARE. Some voices have called for more collaboration between HICARE and NASHIM.

HICARE and NASHIM have similar aims and activities. We haven't, however, discussed the specifics of a possible partnership. These details must first be discussed at working-level meetings of the two organizations.

What are HICARE's next steps?

In regard to our support for survivors overseas, we must promote more autonomous activities in the relevant countries. In addition, it's vital to disseminate information on radiation in order to prevent future nuclear accidents. In 1992, HICARE published a book, “Effects of A-bomb Radiation on the Human Body,” that comprehensively describes the research outcomes involving the medical care of hibakusha in Hiroshima. This book has become recognized widely as a standard reference in the field and we would like to update the data and issue a revised edition.

Keywords

HICARE

HICARE was established in April 1991 to provide support to victims of radiation exposure throughout the world by utilizing the expertise accumulated from the health care of A-bomb survivors and from various research activities on the health effects of radiation. The HICARE organization is composed of major medical institutions in Hiroshima Prefecture and operates on an annual budget, currently about 23 million yen, that is shared equally by Hiroshima Prefecture and Hiroshima City.

The Board of Directors includes the President of the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical Association, the President of the Hiroshima City Medical Association, the Director of Hiroshima University Hospital, the Chairman of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, and the President of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission.

HICARE's primary activities include:

1. inviting physicians, nurses, and medical researchers from overseas for training

2. dispatching physicians and other medical personnel to provide technical guidance and to attend international conferences

3. coordinating educational activities, such as lectures on radiation-related issues

The HICARE office is located at the Atomic Bomb Survivors Affairs Division of the Hiroshima Prefectural Government and eight staff members of the prefectural and the city governments are engaged in the secretariat work of HICARE along with their regular work assignments.