Masao Maruyama recounts A-bombing experience: 1969 interview recorded by Tatsuo Hayashi discovered

Mar. 8, 2013

To be preserved and put to use by Peace Memorial Museum

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

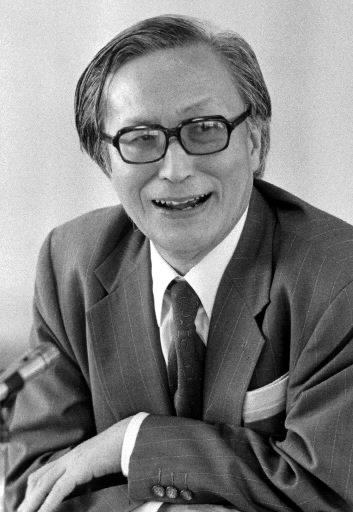

A recorded interview with Masao Maruyama (1914-1996) in which he gives a detailed account of his atomic bombing experience has been discovered. The interview with Mr. Maruyama, a leading scholar of the history of Japanese political thought in the postwar years, was recorded by Tatsuo Hayashi in 1969. Mr. Hayashi, a reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun, had saved the original tapes. He died in December of last year at the age of 79. In his works Mr. Maruyama made almost no reference to his experiences in Hiroshima. A representative of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum said the tapes are “a valuable record” and indicated that the museum would preserved them and make use of them with the cooperation of Mr. Maruyama’s family.

Mr. Maruyama was drafted and assigned to the Imperial Japanese Army Shipping Command, which was located in Ujina (now part of Minami Ward) in Hiroshima. On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was in an open area in front of the command’s office building, 4.6 km from the hypocenter.

The next day, Mr. Maruyama, a private first class and member of the intelligence team, intercepted a radio broadcast of U.S. President Truman’s announcement that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. On August 9 he walked through the ruins of the downtown area of the city with members of the army’s news and photography teams.

The interview with Mr. Maruyama, who was then a professor at the University of Tokyo, was recorded on August 3, 1969, at a Tokyo hospital where he was being treated for hepatitis. It lasted approximately two hours. Part of Mr. Maruyama’s account was published in the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun on August 5 and 6 under a headline saying: “A-bombing experience recounted 24 years later.”

In the recorded interview Mr. Maruyama said, “Even today people are developing diseases related to the atomic bombing. Exactly how can this be explained? This is happening every day in Hiroshima, and poses a new problem for us.”

Mr. Hayashi believed that the tapes might prove useful when examining Mr. Maruyama’s war experience, particularly his A-bombing experience. So in 1998 he transcribed the interview in its entirety and published it in the Research Report Series No. 25 of Hiroshima University’s Institute for Peace Science as an article titled “Masao Maruyama and Hiroshima: the A-bombing Experience of a Political Thinker.” In 2007 a CD of the interview was produced with the assistance of the Tokyo-based Maruyama Masao Techo no Kai, a group dedicated to passing on Mr. Maruyama’s works and ideas.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum learned of the existence of the tapes and contacted Mr. Hayashi’s daughter, who lives in Tokyo. She confirmed that the tapes were at the family home in Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima Prefecture.

Valuable recording pertinent to Fukushima

Comments by Shigeo Kawaguchi, 56, president of the Masao Maruyama Techo no Kai

Mr. Maruyama never said much about his A-bombing experience in conversations with us either. He may have held back because he wondered why he had survived. At the same time, he must have wanted to leave a record of his experience, so he allowed Mr. Hayashi to interview him. This is a valuable recording that raises questions about exposure to radiation that are pertinent to the situation in Fukushima.

Republication of interview with Masao Maruyama

Radiation: “An atomic bomb falling every day”

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Masao Maruyama, a scholar of the history of Japanese political thought, was in Hiroshima at the time of the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945. Mr. Maruyama, whose work had a tremendous impact on the postwar peace and citizens’ movements, died in 1996 at the age of 82 without ever applying for an A-bomb survivor’s certificate. In 1969 he talked with Tatsuo Hayashi, a reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun, about his A-bombing experience and his thoughts on Hiroshima, subjects he did not address in any of his books. The following are excerpts from that recorded interview.

Blinding flash, ghastly sight:Truman’s statement heard on shortwave radio

At the time you were assigned to the Akatsuki Shipping Transport Unit [the Imperial Japanese Army Shipping Command located on the coast in Ujina in Hiroshima’s Minami Ward].

Just as the staff officer was giving a talk, suddenly there was a blinding flash. “Pikadon” [a word that combines expressions for the flash (“pika”) and boom (“don”) of the atomic bomb] really describes it perfectly. By August 8 everyone was saying “pikadon, pikadon.”

Getting back to the bombing, what happened after the flash?

After a little while I crawled out of the air-raid shelter. That’s when I first saw the mushroom cloud. It was impossibly huge and rising very slowly.

Around that time people started streaming in. It must have been about 15 minutes after the bombing. Their clothing was torn, and they arrived by twos and threes, looking dazed. The entire area to the shore was open, but it soon filled with people.

My last memory [of August 6] is the ghastly sight of that open area filled with people.

What happened the next day?

All soldiers were ordered to mobilize to assist the injured and to recover dead bodies. By rights, I should have gone, but the intelligence team leader told me to stay behind. Everyone had left, so I was fooling around with the shortwave radio.

Purely by chance, I picked up the voice of [U.S. President] Truman. He said that an atomic bomb had been dropped. I’d heard the term, but I didn’t really know anything about it.

But I made a note that there had been a broadcast saying that it was an atomic bomb and took it to the staff office. The staff officer said, “All right.” But he didn’t really know what it meant.

It was on the 9th that I walked through the city.

We couldn’t take off on our own, but we tagged along with the officer [in charge of the news team]. I was the only one from the intelligence team. There was a photographer with us.

I saw ghastly sights everywhere. I knew the main streets of Hiroshima, but I couldn’t recognize anything. We also walked around Sentei [Shukkeien Garden in Naka Ward] and the castle.

Those countless bodies. I can still hear the moans of those hundreds of people lying in the open area in front of the shipping command building.

Has your A-bombing experience been significant in the formation of your thought?

There’s no point in trying to fabricate some meaning for it, so I’ll just keep letting it stew inside me. There’s no other way to produce something true without letting everything that builds up stew for a while.

Do you have opportunities to do that?

Yes, with the problem of radiation. I started thinking about that after the Bikini issue [that resulted from the U.S. test of a hydrogen bomb in 1954]. With radiation sickness as well, even though I was young, I understood it based on what I had actually observed. People with injuries that amounted to nothing more than a slight burn were dying before I even got out of the army.

A lot about Hiroshima remains unknown.

What I’ve told you so far is just a tiny fraction of what actually happened. It seems to me that if we don’t put together the experiences of as many people as possible – even the smallest “wayside pebbles” – then we really have only part of the picture. I’m just a wayside pebble, but in that sense I wanted to talk to you.

Please tell me what you think the meaning of Hiroshima is.

It is not just a terrible page in the history of the war. People are still developing diseases related to the atomic bombing. How can you explain the fact that people who have been ill for years and the children of atomic bomb survivors are dying of leukemia? This graphic reality is as if an atomic bomb is being dropped every day. So with this reality of what is taking place, Hiroshima poses a new problem for us every day.

Do you have an A-bomb survivor’s certificate?

I never applied for one because I wasn’t so much a resident of Hiroshima as a bystander.

Masao Maruyama

Born in Osaka in 1914. Graduate of Tokyo Imperial University. Drafted in March 1945 while serving as an assistant professor at the university and assigned to the Imperial Japanese Army’s Shipping Command. Following publication of thesis titled “The Logic and Psychology of Ultra-nationalism” in the magazine “Sekai” in 1946, conducted research on the history of political thought and had a major influence on postwar thought. Major works include “Thought and Behavior in Modern Japanese Politics” and “Senchu to sengo no aida” [Between the War and the Postwar Era]. In 1977, while a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, returned to Hiroshima for the first time in 32 years to deliver a lecture, which marked his final visit to the city. Died on August 15, 1996.

(Originally published on March 4, 2013)