Evacuees reluctant to return home two and a half years after Great East Japan Earthquake

Sep. 20, 2013

by Tsuyoshi Kubota, Staff Writer

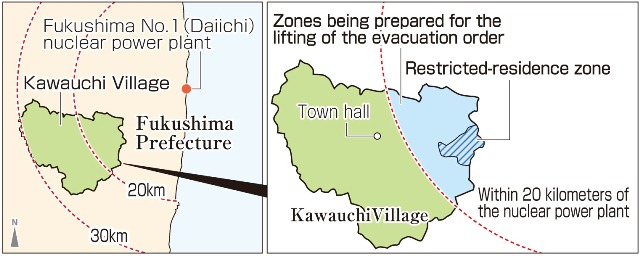

September 11 marked two and a half years since the Great East Japan Earthquake. Some parts of the village of Kawauchi, in Fukushima Prefecture, are located within a radius of 20 kilometers from the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Though town officials have appealed to residents who evacuated from the village to return, less than half the population of roughly 2,800 people has come home. Those reluctant to return hold deep fears over radioactivity in the environment and concerns over the rehabilitation of the town’s economic activity. As a reporter from the Chugoku Shimbun, I paid a visit to Kawauchi, where the residents are struggling to address the arduous tasks of reconstruction.

A banner hangs on the front of the town hall building, proclaiming “Kaeru Kawauchi.” In Japanese, the word “kaeru” has two meanings: “to return” and “frog.” The banner, which boasts the image of a frog, demonstrates the village’s determination to encourage villagers to come back. A sign also bears the message: “Never give up.”

Although the town hall is located in the center of the village, only a few people were seen in the vicinity. “The number of children who play outside has dwindled. Fewer families eat out or go shopping. The faces of the people here have taken on a hard edge,” said Juichi Ide, 60, head of the village’s reconstruction effort, hinting at his impatience.

Those younger than 50 make up just 26% of returnees

In the immediate aftermath of the nuclear accident, town authorities instructed the population of about 3,000 to evacuate the village. Following the start of decontamination work, the town then issued a statement at the end of January 2012 which encouraged residents to return to Kawauchi. As of April 2013, however, the number of people who reside in the town for at least four days a week stands only at 1,299. Just 46% of the population has returned to the village. And when it comes to those younger than 50, in particular, a mere 26% have returned.

The evacuees currently live in as many as 28 prefectures, including Fukushima. Mitsugi Igari, 64, the vice mayor of Kawauchi, said, “Working people and people who are raising children have been reluctant to come back. With a population of less than 1,500, the village can’t be sustained.”

One major obstacle is the fear people feel over exposure to radiation. Even today, the eastern part of the village remains under restrictions, which means that overnight stays in this area are essentially prohibited.

The village has pursued decontamination work, starting at such facilities as schools and clinics. But in some places, one round of decontamination work has not been enough to meet the goal of the effort: to reduce radiation levels below an additional one millisievert of exposure per year.

“I wonder how many years it will take to get the level back to what it was before the accident. I wish I could go back, but I can’t, considering the impact it could have on my children,” explained Ai Otsuka, 39, who now lives in the city of Okayama. Along with her husband, 41, son, 8, and daughter, 4, she continues to live as an evacuee.

Ms. Otsuka serves as the leader of a support group for evacuees. Speaking on behalf of her fellow members, she said, “Our children have grown used to the schools in the communities to which we evacuated. The longer we live as evacuees, the harder many of the mothers feel it would be to go back to Kawauchi.”

The main industries of Kawauchi are agriculture, forestry, and livestock, and the village is seeking to attract companies to the area to create jobs and fuel its reconstruction. A plant called “Kawauchi Highland Agriculture Cultivation Plant,” which cultivates lettuce and herbs with hydroponics, began operating this past April. Lettuce there is grown in a “clean room” which uses no soil, a method that allays the fear of contamination. The room is dazzlingly lit with light-emitting diodes (LED), in red and blue, which are a substitute for sunlight.

Plant operating at 40% capacity

The plant is operated by a company called KiMiDoRi, in which the village and a private company have invested. Though it can ship about 8,000 heads of lettuce at full capacity, it currently operates at just 40% of its potential. This is due to lack of labor: the company would like to hire 25 workers, but the number still stands at 15.

Masakazu Hayakawa, 56, the president of the company, said with chagrin, “To make the plant a model for the new village, I would like to operate it at full capacity. But there aren’t enough people coming here for work.”

Kawauchi has also solicited a convenience store by providing land and a building. It plans to construct such facilities as a supermarket and a funeral hall, too. Mr. Igari said, “The village must pursue business projects that are normally taken care of by the private sector, using them to help encourage our residents to return.” With his words, the vice mayor revealed the plight of the village, unable to foresee its future.

(Originally published on September 12, 2013)

September 11 marked two and a half years since the Great East Japan Earthquake. Some parts of the village of Kawauchi, in Fukushima Prefecture, are located within a radius of 20 kilometers from the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Though town officials have appealed to residents who evacuated from the village to return, less than half the population of roughly 2,800 people has come home. Those reluctant to return hold deep fears over radioactivity in the environment and concerns over the rehabilitation of the town’s economic activity. As a reporter from the Chugoku Shimbun, I paid a visit to Kawauchi, where the residents are struggling to address the arduous tasks of reconstruction.

A banner hangs on the front of the town hall building, proclaiming “Kaeru Kawauchi.” In Japanese, the word “kaeru” has two meanings: “to return” and “frog.” The banner, which boasts the image of a frog, demonstrates the village’s determination to encourage villagers to come back. A sign also bears the message: “Never give up.”

Although the town hall is located in the center of the village, only a few people were seen in the vicinity. “The number of children who play outside has dwindled. Fewer families eat out or go shopping. The faces of the people here have taken on a hard edge,” said Juichi Ide, 60, head of the village’s reconstruction effort, hinting at his impatience.

Those younger than 50 make up just 26% of returnees

In the immediate aftermath of the nuclear accident, town authorities instructed the population of about 3,000 to evacuate the village. Following the start of decontamination work, the town then issued a statement at the end of January 2012 which encouraged residents to return to Kawauchi. As of April 2013, however, the number of people who reside in the town for at least four days a week stands only at 1,299. Just 46% of the population has returned to the village. And when it comes to those younger than 50, in particular, a mere 26% have returned.

The evacuees currently live in as many as 28 prefectures, including Fukushima. Mitsugi Igari, 64, the vice mayor of Kawauchi, said, “Working people and people who are raising children have been reluctant to come back. With a population of less than 1,500, the village can’t be sustained.”

One major obstacle is the fear people feel over exposure to radiation. Even today, the eastern part of the village remains under restrictions, which means that overnight stays in this area are essentially prohibited.

The village has pursued decontamination work, starting at such facilities as schools and clinics. But in some places, one round of decontamination work has not been enough to meet the goal of the effort: to reduce radiation levels below an additional one millisievert of exposure per year.

“I wonder how many years it will take to get the level back to what it was before the accident. I wish I could go back, but I can’t, considering the impact it could have on my children,” explained Ai Otsuka, 39, who now lives in the city of Okayama. Along with her husband, 41, son, 8, and daughter, 4, she continues to live as an evacuee.

Ms. Otsuka serves as the leader of a support group for evacuees. Speaking on behalf of her fellow members, she said, “Our children have grown used to the schools in the communities to which we evacuated. The longer we live as evacuees, the harder many of the mothers feel it would be to go back to Kawauchi.”

The main industries of Kawauchi are agriculture, forestry, and livestock, and the village is seeking to attract companies to the area to create jobs and fuel its reconstruction. A plant called “Kawauchi Highland Agriculture Cultivation Plant,” which cultivates lettuce and herbs with hydroponics, began operating this past April. Lettuce there is grown in a “clean room” which uses no soil, a method that allays the fear of contamination. The room is dazzlingly lit with light-emitting diodes (LED), in red and blue, which are a substitute for sunlight.

Plant operating at 40% capacity

The plant is operated by a company called KiMiDoRi, in which the village and a private company have invested. Though it can ship about 8,000 heads of lettuce at full capacity, it currently operates at just 40% of its potential. This is due to lack of labor: the company would like to hire 25 workers, but the number still stands at 15.

Masakazu Hayakawa, 56, the president of the company, said with chagrin, “To make the plant a model for the new village, I would like to operate it at full capacity. But there aren’t enough people coming here for work.”

Kawauchi has also solicited a convenience store by providing land and a building. It plans to construct such facilities as a supermarket and a funeral hall, too. Mr. Igari said, “The village must pursue business projects that are normally taken care of by the private sector, using them to help encourage our residents to return.” With his words, the vice mayor revealed the plight of the village, unable to foresee its future.

(Originally published on September 12, 2013)