A-bomb survivors share stories of the bombing with children visiting Hiroshima

Jul. 18, 2008

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Every May and June, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park fills with students on field trips from all over Japan. These groups of children are a common sight this season. Last month, I sat on the ground by monuments in the park and on a chair in Peace Memorial Museum to hear A-bomb survivors share their stories of the bombing with three groups of elementary and junior high school students from other prefectures.

The three survivors that spoke to these groups of children are all at least 77 years old and have been recounting their experiences for over 20 years. Memories of the lost neighborhoods, a sense of guilt toward the dead, the anguish of dreams abandoned. . . The hour-long talks place less emphasis on the horror of the bombing or pleas for nuclear abolition than what the atomic bomb has done to each individual personally.

Speaking familiarly, as if to their own grandchildren, the speakers drew the youngsters into their stories. The students seemed to read the depth of the survivors’ emotional scars in their tears. Hearing these stories directly from the people who lived through them--even 63 years later--stirred their hearts.

Kanji Yamasaki: “My whole neighborhood disappeared”

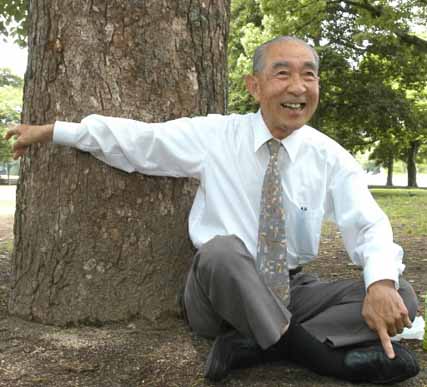

“Right over there near the entrance to the museum, that’s where I lived. Come on, I’ll show you.” Kanji Yamasaki, 80 years old, from Fuchu Town in Hiroshima Prefecture, led 18 sixth-graders from Yamate Elementary School in Akashi City, Hyogo Prefecture, to the monument for the victims of Tenjin-machi Kitagumi (now, Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward). He sat down with his back against the trunk of a large camphor tree and motioned the children to perch in front of him.

“When we were kids, we used to play tag right around here. If we couldn’t outrun whoever was ‘it,’ we jumped into the Motoyasu River. We even snuck into the building that became the A-bomb Dome. If we got caught sliding down the banister of the spiral staircase, we got yelled at.”

One after another, boyhood memories bubbled up. The children’s eyes were glued to Mr. Yamasaki’s expressive face as they scribbled down notes.

When Mr. Yamasaki was in the 4th grade, his father, who sold musical instruments and antique works of art, passed away. Mr. Yamasaki and his mother then moved to Tenjin-machi Kitagumi, which faces the Motoyasu River. His house stood in the vicinity of the present Peace Memorial Museum.

A single explosion obliterated his neighborhood. It stole away his mother, aunt, uncle, and cousins--all together, 19 family members and relatives. His mother’s remains were never found. When he places his palms together in front of her empty grave, he feels intense anguish over her fate.

“My whole neighborhood disappeared because of the bomb. Think about your own homes for a moment. Wouldn’t it be terrible to lose your entire neighborhood?” The students nodded deeply.

“I couldn’t bear it,” said Kiriko Sonoda, 12, pondering such consequences of war for the first time. “I hate war.”

Mr. Yamasaki was exposed to the bomb roughly 1.5 kilometers from Hiroshima Second Middle School (now, Kanon High School). The subsequent rumors that “when your hair falls out you’re done for” provoked such fear that he used to yank on his hair every night to test it.

Mr. Yamasaki becomes most animated when sharing memories of Tenjin-machi Kitagumi. “Telling stories about my relatives who were killed by the bomb is the only way I can honor them.” If listening to survivor accounts helps children consider the meaning of peace, Mr. Yamasaki should continue to share his experience as long as he possibly can.

Norio Morimoto: “I don’t want these children to suffer like I did”

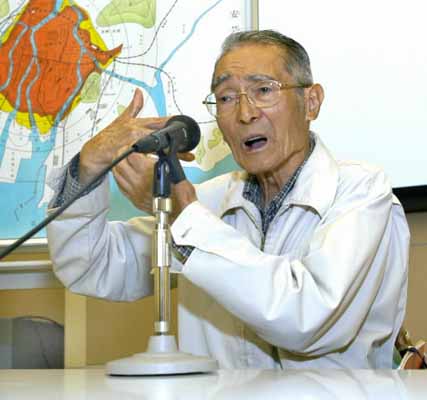

Encouragement from other A-bomb survivors inspires Norio Morimoto, 80 years old, from Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, to continue to tell his story.

Mr. Morimoto speaks softly and prefers to use a microphone indoors. Because he wants the children to listen “with their hearts,” he starts by asking them to put away their writing tools and notebooks.

Mr. Morimoto was exposed at age 17 at a distance of 1.1 kilometers. The friend standing next to him was killed instantly. When Mr. Morimoto came to, he was lying on the ground. “I was saved because my friend shielded me with his body.”

Mr. Morimoto’s dream was to become a teacher. However, he could not go on to college due to the chaos of the post-war period and, eventually, he earned a living by collecting utility and newspaper bills.

In 1983, Mr. Morimoto was asked to stand in and provide his testimony at a symposium when another survivor became unable to take part. He reluctantly accepted that first speaking opportunity, but was then persuaded to join a group of A-bomb storytellers the following year.

“I didn’t really go to school…” Mr. Morimoto felt embarrassed at his lack of education, but overcame this difficulty through his experience of the students who came to hear him. Though some initially turned away, they would gradually face him fully and, by the end of his story, they shed tears.

He began squeezing in talks to students at Peace Memorial Park during his workday. When he could not meet his targets as a bill collector, his boss told him, “You’re just hanging out at Peace Park, aren’t you?” The insult only deepened his commitment to his new role as an A-bomb storyteller.

A quarter of a century later, most of the survivors who brought him into their group have passed on. Others, he said, would still speak were they not confined to hospitals or nursing homes.

Mr. Morimoto does not tell his story to gain sympathy. “War stole my dreams and saddled me with memories of terrible cruelty. I don’t want these children to suffer like I did. I want them to know the truth about war.”

Kawk Bok-soon: Feeling guilt over surviving the bomb

Kawk Bok-soon was exposed to the bomb just 900 meters from the hypocenter. Though most people in her district of Otemachi instantly burned to death, Kawk Bok-soon, now 79 years old and a resident of Nishi Ward, survives to this day. At the time, she was a 16-year-old live-in servant.

Though her legs are covered with scars, her face bears no sign of the bomb. “You’re lying. Everyone in that area was melted by the bomb.” Even some survivors are incredulous when Ms. Kawk reveals where she was exposed. Ms. Kawk herself is mystified that she survived so close to the hypocenter.

Her memories of what happened after the explosion are fragmentaryHe remembers what happened next iin fragments. Though she lacks a linear story, Ms. Kawk relates the episodes she remembers with earnest intensity.

Ms. Kawk has been providing witness for 20 years, but she still has to clutch a handkerchief no matter who she speaks to. Reliving her experience through the retelling, she chokes up and weeps at the same places each time.

She describes bloated corpses, eyeless soldiers floating in the river, and bodies bouncing on makeshift stretchers. The longer she speaks, the more Ms. Kawk’s grief for the children and women--all the indiscriminate victims--overcomes her.

“I felt Ms. Kawk’s guilt for having survived,” said Shiori Wakayama, 13, an 8th grader at Kansai Soka Junior High School in Katano City, Osaka. She heard Ms. Kawk speak in the museum on June 19 and, imagining herself in Ms. Kawk’s position, she wept.

Raising three sons and a daughter, Ms. Kawk was hard pressed to keep food on the table. Plagued by pain in many parts of her body, and hospitalized repeatedly with cancer in her urethra, bladder, and kidney, she calls her experience “a half-century of hell.” She says that telling her story is exhausting and constantly crying in front of children is embarrassing. She often wonders if she should really be doing this.

Still, Ms. Kawk is able to fire herself up by recalling her gratitude for having survived and her mission, her duty, “to talk about the A-bomb experience on behalf of the victims.” Ms. Kawk will continue to share her story with children this summer at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

(Originally published on July 7, 2008)

Related articles

Growing old, A-bomb survivors are committed to their testimony activities(July 7, 2008)

Every May and June, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park fills with students on field trips from all over Japan. These groups of children are a common sight this season. Last month, I sat on the ground by monuments in the park and on a chair in Peace Memorial Museum to hear A-bomb survivors share their stories of the bombing with three groups of elementary and junior high school students from other prefectures.

The three survivors that spoke to these groups of children are all at least 77 years old and have been recounting their experiences for over 20 years. Memories of the lost neighborhoods, a sense of guilt toward the dead, the anguish of dreams abandoned. . . The hour-long talks place less emphasis on the horror of the bombing or pleas for nuclear abolition than what the atomic bomb has done to each individual personally.

Speaking familiarly, as if to their own grandchildren, the speakers drew the youngsters into their stories. The students seemed to read the depth of the survivors’ emotional scars in their tears. Hearing these stories directly from the people who lived through them--even 63 years later--stirred their hearts.

Kanji Yamasaki: “My whole neighborhood disappeared”

“Right over there near the entrance to the museum, that’s where I lived. Come on, I’ll show you.” Kanji Yamasaki, 80 years old, from Fuchu Town in Hiroshima Prefecture, led 18 sixth-graders from Yamate Elementary School in Akashi City, Hyogo Prefecture, to the monument for the victims of Tenjin-machi Kitagumi (now, Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward). He sat down with his back against the trunk of a large camphor tree and motioned the children to perch in front of him.

“When we were kids, we used to play tag right around here. If we couldn’t outrun whoever was ‘it,’ we jumped into the Motoyasu River. We even snuck into the building that became the A-bomb Dome. If we got caught sliding down the banister of the spiral staircase, we got yelled at.”

One after another, boyhood memories bubbled up. The children’s eyes were glued to Mr. Yamasaki’s expressive face as they scribbled down notes.

When Mr. Yamasaki was in the 4th grade, his father, who sold musical instruments and antique works of art, passed away. Mr. Yamasaki and his mother then moved to Tenjin-machi Kitagumi, which faces the Motoyasu River. His house stood in the vicinity of the present Peace Memorial Museum.

A single explosion obliterated his neighborhood. It stole away his mother, aunt, uncle, and cousins--all together, 19 family members and relatives. His mother’s remains were never found. When he places his palms together in front of her empty grave, he feels intense anguish over her fate.

“My whole neighborhood disappeared because of the bomb. Think about your own homes for a moment. Wouldn’t it be terrible to lose your entire neighborhood?” The students nodded deeply.

“I couldn’t bear it,” said Kiriko Sonoda, 12, pondering such consequences of war for the first time. “I hate war.”

Mr. Yamasaki was exposed to the bomb roughly 1.5 kilometers from Hiroshima Second Middle School (now, Kanon High School). The subsequent rumors that “when your hair falls out you’re done for” provoked such fear that he used to yank on his hair every night to test it.

Mr. Yamasaki becomes most animated when sharing memories of Tenjin-machi Kitagumi. “Telling stories about my relatives who were killed by the bomb is the only way I can honor them.” If listening to survivor accounts helps children consider the meaning of peace, Mr. Yamasaki should continue to share his experience as long as he possibly can.

Norio Morimoto: “I don’t want these children to suffer like I did”

Encouragement from other A-bomb survivors inspires Norio Morimoto, 80 years old, from Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, to continue to tell his story.

Mr. Morimoto speaks softly and prefers to use a microphone indoors. Because he wants the children to listen “with their hearts,” he starts by asking them to put away their writing tools and notebooks.

Mr. Morimoto was exposed at age 17 at a distance of 1.1 kilometers. The friend standing next to him was killed instantly. When Mr. Morimoto came to, he was lying on the ground. “I was saved because my friend shielded me with his body.”

Mr. Morimoto’s dream was to become a teacher. However, he could not go on to college due to the chaos of the post-war period and, eventually, he earned a living by collecting utility and newspaper bills.

In 1983, Mr. Morimoto was asked to stand in and provide his testimony at a symposium when another survivor became unable to take part. He reluctantly accepted that first speaking opportunity, but was then persuaded to join a group of A-bomb storytellers the following year.

“I didn’t really go to school…” Mr. Morimoto felt embarrassed at his lack of education, but overcame this difficulty through his experience of the students who came to hear him. Though some initially turned away, they would gradually face him fully and, by the end of his story, they shed tears.

He began squeezing in talks to students at Peace Memorial Park during his workday. When he could not meet his targets as a bill collector, his boss told him, “You’re just hanging out at Peace Park, aren’t you?” The insult only deepened his commitment to his new role as an A-bomb storyteller.

A quarter of a century later, most of the survivors who brought him into their group have passed on. Others, he said, would still speak were they not confined to hospitals or nursing homes.

Mr. Morimoto does not tell his story to gain sympathy. “War stole my dreams and saddled me with memories of terrible cruelty. I don’t want these children to suffer like I did. I want them to know the truth about war.”

Kawk Bok-soon: Feeling guilt over surviving the bomb

Kawk Bok-soon was exposed to the bomb just 900 meters from the hypocenter. Though most people in her district of Otemachi instantly burned to death, Kawk Bok-soon, now 79 years old and a resident of Nishi Ward, survives to this day. At the time, she was a 16-year-old live-in servant.

Though her legs are covered with scars, her face bears no sign of the bomb. “You’re lying. Everyone in that area was melted by the bomb.” Even some survivors are incredulous when Ms. Kawk reveals where she was exposed. Ms. Kawk herself is mystified that she survived so close to the hypocenter.

Her memories of what happened after the explosion are fragmentaryHe remembers what happened next iin fragments. Though she lacks a linear story, Ms. Kawk relates the episodes she remembers with earnest intensity.

Ms. Kawk has been providing witness for 20 years, but she still has to clutch a handkerchief no matter who she speaks to. Reliving her experience through the retelling, she chokes up and weeps at the same places each time.

She describes bloated corpses, eyeless soldiers floating in the river, and bodies bouncing on makeshift stretchers. The longer she speaks, the more Ms. Kawk’s grief for the children and women--all the indiscriminate victims--overcomes her.

“I felt Ms. Kawk’s guilt for having survived,” said Shiori Wakayama, 13, an 8th grader at Kansai Soka Junior High School in Katano City, Osaka. She heard Ms. Kawk speak in the museum on June 19 and, imagining herself in Ms. Kawk’s position, she wept.

Raising three sons and a daughter, Ms. Kawk was hard pressed to keep food on the table. Plagued by pain in many parts of her body, and hospitalized repeatedly with cancer in her urethra, bladder, and kidney, she calls her experience “a half-century of hell.” She says that telling her story is exhausting and constantly crying in front of children is embarrassing. She often wonders if she should really be doing this.

Still, Ms. Kawk is able to fire herself up by recalling her gratitude for having survived and her mission, her duty, “to talk about the A-bomb experience on behalf of the victims.” Ms. Kawk will continue to share her story with children this summer at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

(Originally published on July 7, 2008)

Related articles

Growing old, A-bomb survivors are committed to their testimony activities(July 7, 2008)