Toward a nuclear-free world: British witnesses to Cold War publish essay

Nov. 15, 2008

by Uzaemonnaotsuka Tokai

Support for the abolition of nuclear weapons is growing in the United Kingdom, one of the world’s nuclear nations. In January of this year Prime Minister Gordon Brown declared, “I pledge that in the run-up to the Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in 2010 we will be at the forefront of the international campaign to accelerate disarmament amongst possessor states.” At the Geneva Conference on Disarmament in February, Des Browne, British Defence Secretary, said, “I too want the U.K. to be seen as a ‘disarmament laboratory.’” A change in U.K. policy may have an impact on the nuclear policies of the United States, Russia and other countries. The Chugoku Shimbun looked into the background behind the growing support for nuclear abolition and the problems in achieving it.

In June, a jointly written article advocating the abolition of nuclear weapons and featuring a headline that said “Start worrying and learn to ditch the bomb” took up nearly an entire page in The Times.

The article described the writers’ concern about nuclear terrorism: “During the Cold War nuclear weapons had the perverse effect of making the world a relatively stable place. That is no longer the case. Instead, the world is at the brink of a new and dangerous phase,” it said. “The ultimate aspiration should be to have a world free of nuclear weapons.”

The article was written by three former Foreign Secretaries, including Sir Malcolm Rifkind, 62, a Member of Parliament, and Lord George Robertson, former Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. All four witnessed the era in which the number of nuclear warheads dramatically increased with the growing faith in the theory of nuclear deterrence.

Why have they changed their positions now? One of the writers, former Foreign Secretary Rifkind, agreed to be interviewed in the Portcullis House next to the Houses of Parliament.

“Britain is changing. We have realized that we must not go back to the days of the Cold War in which we lived in fear of nuclear war,” he said. “With the war on terror, including the Iraq war, there has been growing criticism of Britain’s subservience to the U.S., and the anti-neoconservative trend is spreading throughout Europe.”

Mark Fitzpatrick, 54, a senior researcher at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, said, “The U.K labor government is very sincere in their desire to see a world free of nuclear weapons. This is actually a long standing hope among the many people particularly in the labor party. This peaceful ideology is getting stronger. This can be seen in the statements by Prime Minister Brown and in the article.”

Sir Lawrence Freedman, 59, is Professor of War Studies and Vice Principal at King’s College, London, specializing in security theory. He analyzes the situation this way: “In terms of security, Britain is the country that can most easily abolish its nuclear weapons. In terms of finances as well, there is sentiment in the administration in favor of changing the nuclear policy.”

In a report titled “National Security Strategy” published this spring, the British government primarily addressed the issues of immigration and the environment, and there was very little reference to military threats.

Nevertheless, there is no indication that Britain is about to make a drastic shift to abandon its nuclear weapons all at once. In fact, last year the House of Commons approved a plan to update its submarine-launched nuclear missile system. About ?20 billion will be spent making it possible to maintain the nuclear missile system for the next 40 years.

Fitzpatrick said, “In order to eliminate nuclear weapons, nations must cooperate on arms reduction. It will take about 20 years.” He cited several specific issues that must be addressed including a system for the monitoring of nuclear materials, tighter regulations for nations that have not signed the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, and further developing reliability in areas in which there is concern about potential conflicts.

At the Portcullis House, Mr. Rifkind continued, “In the past, Britain was opposed to abolition on the grounds that the genie of nuclear weapons was out of the bottle and could not be put back. But now the government has changed its position and believes it would be foolish not to change the situation. It can be done. If the nations of the world band together, nuclear weapons can be abolished.” He also said he hoped that Japan, the only nation to have suffered nuclear attacks, would take the lead in this effort.

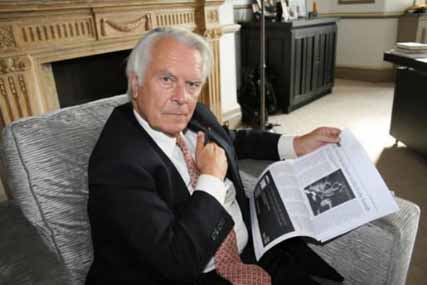

David Owen, former Foreign Secretary: Cuts are possible with concerted action

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed former British Foreign Secretary David Owen, 70, one of the writers of an article published in the The Times calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Why did you call for the abolition of nuclear weapons?

During the Cold War, people came to believe that nuclear weapons were a stabilizing force in the world, but now with the proliferation of nuclear technology the world is becoming increasingly unstable. The North Korea problem is one example. And there is increasing concern about nuclear weapons falling into the hands of terrorists.

I was also influenced by the recent recommendations made by former U.S. Secretary of State [Henry] Kissinger and others. As a politician in a nuclear nation, I felt I had a responsibility to react to Kissinger’s campaign and express my philosophy on future nuclear policy.

Can the British government change its nuclear policy?

Now we’re at the pre-change stage. In the future the number of nuclear warheads will decrease, but the submarines that carry them will exist for nearly another 40 years. The government basically believes in nuclear deterrence.

Isn’t there a contradiction between what the prime minister says and what the government does?

Dividing people into two categories--those who hate nuclear weapons and those who support them--is an oversimplification. It is not a double standard to recognize the danger of nuclear weapons while at the same time believing that they are necessary.

Many people believed that slavery should be abolished, but it took many years to actually free the slaves. I think the same thing will happen with nuclear weapons. Britain has taken the first step toward a nuclear-free world and it seeks to lay the foundation for this world to be realized.

When can nuclear weapons be abolished?

It will be difficult for the U.K. to abolish them unilaterally. In the first phase, the U.K. must work in concert with other nuclear nations to reduce the number of nuclear warheads. In the second phase, the nuclear superpowers of the U.S. and Russia must make major cuts in their nuclear arsenals.

This is my personal opinion, but I think it would be possible to adopt a joint strategy with France. If the U.S. and Russia move forward with cuts to their nuclear weapons, our two countries may voluntarily abolish our nuclear weapons.

The world has not yet reached the first phase. It is essential to build mutual trust between nations as part of the process. We may not be able to do it within the next 20 years, but nuclear abolition is possible.

Changing attitude of military town: Spirit of Hiroshima spreads

After getting off the train in Helensburgh, population 14,000, 40 km west of Glasgow, Scotland, I went by car to the top of a small hill from which the Faslane Nuclear Base could be seen.

The base is situated on the long, narrow Gare Loch, into which the River Clyde flows. The sky was covered with a thick layer of clouds. The topography and climate make the area difficult to attack by sea or by air, and these were the determining factors in its selection as the site for the U.K.’s only base for Trident-armed nuclear submarines.

Security cameras line the 3-meter high fence at the main gate, and armed soldiers glare at visitors, making it clear why this site is known for having the tightest security in the U.K.

The U.K. has four nuclear submarines armed with Trident missiles, each of which is said to carry under tight security an important letter: “final orders” written by each prime minister after taking office. If the country were to suffer a devastating attack by an enemy and the lines of communication between the submarines and Admiralty House, the naval headquarters, were cut, the letter is to be opened. The Sunday Times reported that during the Cold War the contents were as follows: “Firstly, put yourself under U.S. command, if it still exists. Secondly, go to Australia, if it’s still there. Thirdly, fire your nuclear missiles at the enemy we are at war with. Finally, use your own judgement.”

I met with Eric Thompson, 64, who retired from the Navy 10 years ago and still lives in town. He served aboard submarines for 25 years as an engineer. He went out to sea for two months at a time, always wondering when the letter might be opened. He said he often had nightmares. “I thought I might come ashore one day to find my hometown and my family reduced to ashes,” he said.

But once the Cold War ended his thinking changed. “The U.K. has no enemies. I began to wonder whether it was really necessary to have nuclear weapons. As a veteran of the navy, I feel the dilemma,” he said.

The attitude of the local community is rapidly changing. In the past it was felt that the base was essential for the local economy, but last year citizens blockaded the base.

Jane Tallents, 50, a member of a local anti-nuclear group, took me to the top of a hill overlooking the base from the opposite shore. “I hope the day will come when it will not be necessary to have a letter ordering nuclear retaliation,” she said as she looked down upon the base. “A world in which we can threaten each other with nuclear weapons will not lead to peace. The spirit of Hiroshima is spreading in the U.K.”

(Originally published on November 3, 2008)

Support for the abolition of nuclear weapons is growing in the United Kingdom, one of the world’s nuclear nations. In January of this year Prime Minister Gordon Brown declared, “I pledge that in the run-up to the Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in 2010 we will be at the forefront of the international campaign to accelerate disarmament amongst possessor states.” At the Geneva Conference on Disarmament in February, Des Browne, British Defence Secretary, said, “I too want the U.K. to be seen as a ‘disarmament laboratory.’” A change in U.K. policy may have an impact on the nuclear policies of the United States, Russia and other countries. The Chugoku Shimbun looked into the background behind the growing support for nuclear abolition and the problems in achieving it.

In June, a jointly written article advocating the abolition of nuclear weapons and featuring a headline that said “Start worrying and learn to ditch the bomb” took up nearly an entire page in The Times.

The article described the writers’ concern about nuclear terrorism: “During the Cold War nuclear weapons had the perverse effect of making the world a relatively stable place. That is no longer the case. Instead, the world is at the brink of a new and dangerous phase,” it said. “The ultimate aspiration should be to have a world free of nuclear weapons.”

The article was written by three former Foreign Secretaries, including Sir Malcolm Rifkind, 62, a Member of Parliament, and Lord George Robertson, former Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. All four witnessed the era in which the number of nuclear warheads dramatically increased with the growing faith in the theory of nuclear deterrence.

Why have they changed their positions now? One of the writers, former Foreign Secretary Rifkind, agreed to be interviewed in the Portcullis House next to the Houses of Parliament.

“Britain is changing. We have realized that we must not go back to the days of the Cold War in which we lived in fear of nuclear war,” he said. “With the war on terror, including the Iraq war, there has been growing criticism of Britain’s subservience to the U.S., and the anti-neoconservative trend is spreading throughout Europe.”

Mark Fitzpatrick, 54, a senior researcher at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, said, “The U.K labor government is very sincere in their desire to see a world free of nuclear weapons. This is actually a long standing hope among the many people particularly in the labor party. This peaceful ideology is getting stronger. This can be seen in the statements by Prime Minister Brown and in the article.”

Sir Lawrence Freedman, 59, is Professor of War Studies and Vice Principal at King’s College, London, specializing in security theory. He analyzes the situation this way: “In terms of security, Britain is the country that can most easily abolish its nuclear weapons. In terms of finances as well, there is sentiment in the administration in favor of changing the nuclear policy.”

In a report titled “National Security Strategy” published this spring, the British government primarily addressed the issues of immigration and the environment, and there was very little reference to military threats.

Nevertheless, there is no indication that Britain is about to make a drastic shift to abandon its nuclear weapons all at once. In fact, last year the House of Commons approved a plan to update its submarine-launched nuclear missile system. About ?20 billion will be spent making it possible to maintain the nuclear missile system for the next 40 years.

Fitzpatrick said, “In order to eliminate nuclear weapons, nations must cooperate on arms reduction. It will take about 20 years.” He cited several specific issues that must be addressed including a system for the monitoring of nuclear materials, tighter regulations for nations that have not signed the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, and further developing reliability in areas in which there is concern about potential conflicts.

At the Portcullis House, Mr. Rifkind continued, “In the past, Britain was opposed to abolition on the grounds that the genie of nuclear weapons was out of the bottle and could not be put back. But now the government has changed its position and believes it would be foolish not to change the situation. It can be done. If the nations of the world band together, nuclear weapons can be abolished.” He also said he hoped that Japan, the only nation to have suffered nuclear attacks, would take the lead in this effort.

David Owen, former Foreign Secretary: Cuts are possible with concerted action

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed former British Foreign Secretary David Owen, 70, one of the writers of an article published in the The Times calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Why did you call for the abolition of nuclear weapons?

During the Cold War, people came to believe that nuclear weapons were a stabilizing force in the world, but now with the proliferation of nuclear technology the world is becoming increasingly unstable. The North Korea problem is one example. And there is increasing concern about nuclear weapons falling into the hands of terrorists.

I was also influenced by the recent recommendations made by former U.S. Secretary of State [Henry] Kissinger and others. As a politician in a nuclear nation, I felt I had a responsibility to react to Kissinger’s campaign and express my philosophy on future nuclear policy.

Can the British government change its nuclear policy?

Now we’re at the pre-change stage. In the future the number of nuclear warheads will decrease, but the submarines that carry them will exist for nearly another 40 years. The government basically believes in nuclear deterrence.

Isn’t there a contradiction between what the prime minister says and what the government does?

Dividing people into two categories--those who hate nuclear weapons and those who support them--is an oversimplification. It is not a double standard to recognize the danger of nuclear weapons while at the same time believing that they are necessary.

Many people believed that slavery should be abolished, but it took many years to actually free the slaves. I think the same thing will happen with nuclear weapons. Britain has taken the first step toward a nuclear-free world and it seeks to lay the foundation for this world to be realized.

When can nuclear weapons be abolished?

It will be difficult for the U.K. to abolish them unilaterally. In the first phase, the U.K. must work in concert with other nuclear nations to reduce the number of nuclear warheads. In the second phase, the nuclear superpowers of the U.S. and Russia must make major cuts in their nuclear arsenals.

This is my personal opinion, but I think it would be possible to adopt a joint strategy with France. If the U.S. and Russia move forward with cuts to their nuclear weapons, our two countries may voluntarily abolish our nuclear weapons.

The world has not yet reached the first phase. It is essential to build mutual trust between nations as part of the process. We may not be able to do it within the next 20 years, but nuclear abolition is possible.

Changing attitude of military town: Spirit of Hiroshima spreads

After getting off the train in Helensburgh, population 14,000, 40 km west of Glasgow, Scotland, I went by car to the top of a small hill from which the Faslane Nuclear Base could be seen.

The base is situated on the long, narrow Gare Loch, into which the River Clyde flows. The sky was covered with a thick layer of clouds. The topography and climate make the area difficult to attack by sea or by air, and these were the determining factors in its selection as the site for the U.K.’s only base for Trident-armed nuclear submarines.

Security cameras line the 3-meter high fence at the main gate, and armed soldiers glare at visitors, making it clear why this site is known for having the tightest security in the U.K.

The U.K. has four nuclear submarines armed with Trident missiles, each of which is said to carry under tight security an important letter: “final orders” written by each prime minister after taking office. If the country were to suffer a devastating attack by an enemy and the lines of communication between the submarines and Admiralty House, the naval headquarters, were cut, the letter is to be opened. The Sunday Times reported that during the Cold War the contents were as follows: “Firstly, put yourself under U.S. command, if it still exists. Secondly, go to Australia, if it’s still there. Thirdly, fire your nuclear missiles at the enemy we are at war with. Finally, use your own judgement.”

I met with Eric Thompson, 64, who retired from the Navy 10 years ago and still lives in town. He served aboard submarines for 25 years as an engineer. He went out to sea for two months at a time, always wondering when the letter might be opened. He said he often had nightmares. “I thought I might come ashore one day to find my hometown and my family reduced to ashes,” he said.

But once the Cold War ended his thinking changed. “The U.K. has no enemies. I began to wonder whether it was really necessary to have nuclear weapons. As a veteran of the navy, I feel the dilemma,” he said.

The attitude of the local community is rapidly changing. In the past it was felt that the base was essential for the local economy, but last year citizens blockaded the base.

Jane Tallents, 50, a member of a local anti-nuclear group, took me to the top of a hill overlooking the base from the opposite shore. “I hope the day will come when it will not be necessary to have a letter ordering nuclear retaliation,” she said as she looked down upon the base. “A world in which we can threaten each other with nuclear weapons will not lead to peace. The spirit of Hiroshima is spreading in the U.K.”

(Originally published on November 3, 2008)